Section Branding

Header Content

With Kids OKed For COVID-19 Vaccines, New Access Gaps Emerge

Primary Content

Children between 12 and 15 years old are now allowed to be vaccinated against COVID-19 in Georgia, and around the country. That sets up a challenge in bridging a wide gap in vaccine access between the moneyed north of Georgia and the rest of the state.

When the FDA authorized the Pfizer vaccine for young people Monday, Georgia’s Department of Public Health told health departments who had it to start immunizing.

“We were aware of parents who wanted to have their children vaccinated and did not want to run the risk of asking people to return in 48 hours and having them not come back,” DPH spokesperson Nancy Nydam said.

In general, that meant even as private health care providers waited for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's OK that came a day later, health departments in metro Atlanta and most of north Georgia were able to begin vaccinating young people Tuesday — even at the mass vaccination site at the Mercedes-Benz Stadium. There were some vaccinations of young people on the coast, too.

That’s because those health departments could afford the expensive cold storage needed for the Pfizer vaccine.

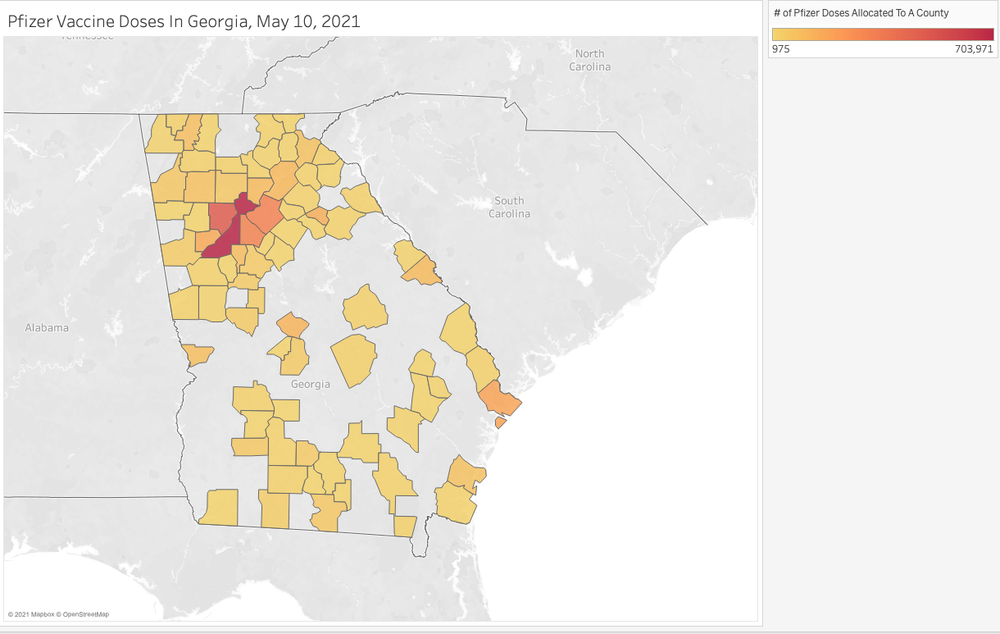

But a look at the May 10 DPH vaccine order list suggests that, for much of the rest of the state, there is no Pfizer vaccine at all.

In southwest Georgia, Phoebe Putney Health System has long had a steady supply of Pfizer vaccine at their Albany vaccination site while health departments in surrounding counties have not. Those are the places Phoebe has been taking its mobile vaccination operations, but so far, those have been kitted out with Moderna doses, which are not yet authorized for children.

Dr. Kavanaugh Chandler is the chief operating officer of Community Health Care Systems, a chain of 17 clinics in rural east central Georgia that see all patients regardless of their ability to pay. That includes clinics in communities such as Hancock County, which has seen the highest per capita COVID-19 death rate in the state but has no Pfizer vaccine on hand. Chandler said storing the Pfizer vaccine in smaller, less resourced clinics has been a problem from the beginning.

“The recent announcement is one that requires us to pivot a little bit, as we were predominantly using Moderna,” Chandler said.

Part of the pivot is telling patients in any of the 17 CHCS clinics where they can find the Pfizer vaccine. Another part is getting their hands on their own supply and keeping it cool.

“And so we're trying to figure that out now through how, if we were to get supplies, how we go about storing and managing it,” he said.

Mobile, rural vaccination efforts by Fair Count and the emergency response nonprofit CORE also face a similar challenge.

For the time being, U.S. Census data suggest that about 70,000 children in Georgia may not have easy access to COVID-19 vaccinations.