Caption

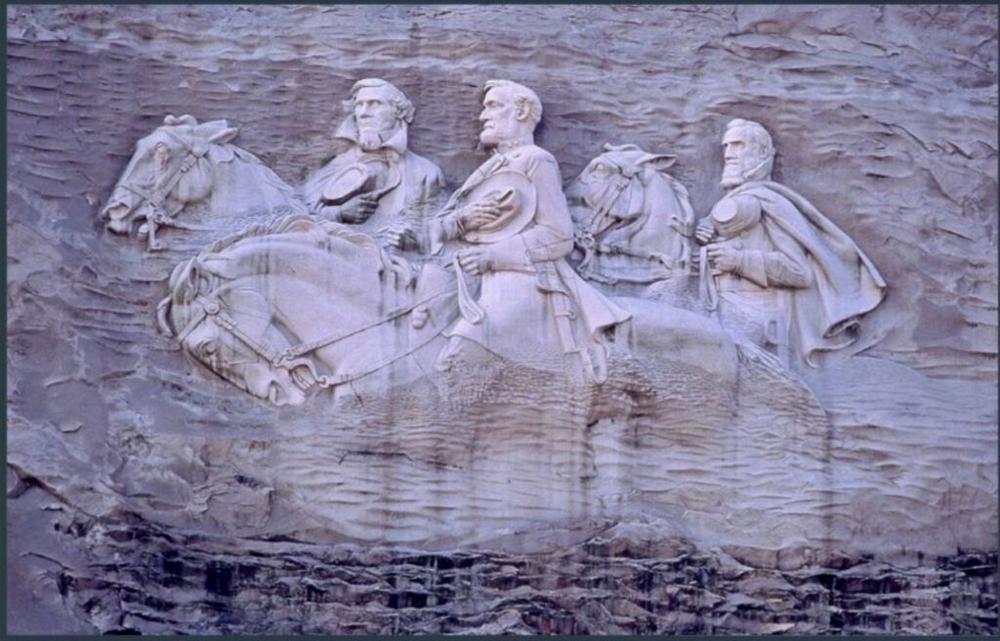

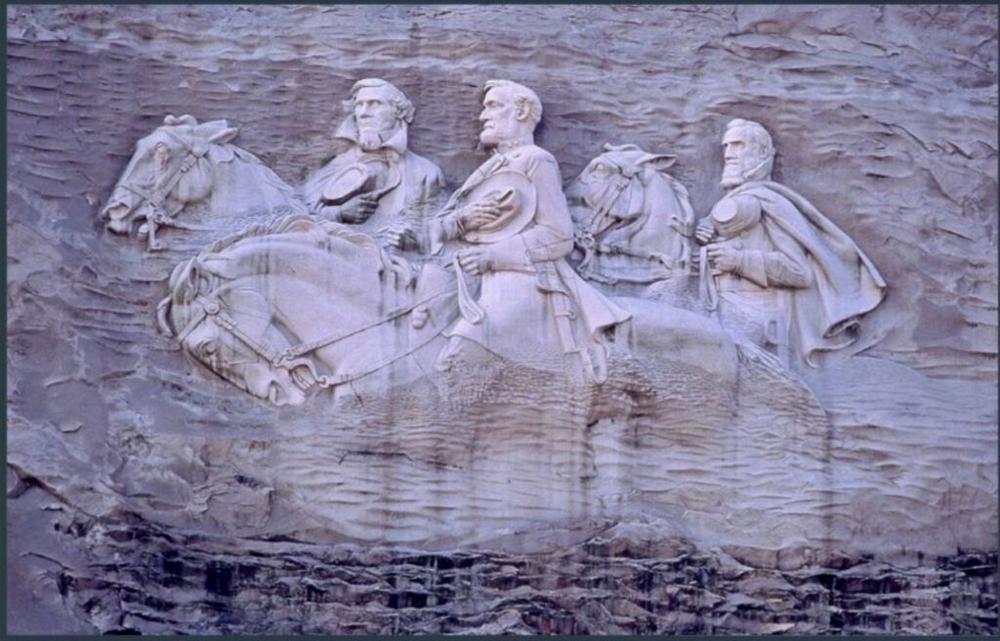

Left to right: Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson are carved into the side of Stone Mountain.

Credit: Stone Mountain Memorial Association

Left to right: Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson are carved into the side of Stone Mountain.

Proposals to add historical context around the Confederate carving at Stone Mountain are set to face a vote Monday amid calls to remove the controversial monument and backlash from its supporters.

The upcoming vote marks the first moves by the Stone Mountain Memorial Association to address longstanding outrage over the giant carving on the mountain’s side, which depicts Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

The proposals for an exhibit about the carving’s history as a post-Civil War memorial to the Confederacy and the removal of several Confederate flags to other areas of the park aim to balance passions on both sides of the issue and curb financial losses caused in part by the controversy, according to the association’s CEO, Bill Stephens.

“I believe you can’t cancel history and you can’t run from it,” Stephens said at an April 26 meeting in which he unveiled the proposals. “We believe in additions, not subtractions.”

The proposed exhibit for the carving would give an “honest telling of the whole story” on the mountain’s history as the site where the Ku Klux Klan was revived in 1915, as well as its significance as the world’s largest granite formation and “a gathering place since pre-history,” according to a summary of the proposals.

A set of flags including the Confederate battle emblem that stand beneath the 90-foot-tall carving would be relocated to a new site allowing “stronger identification with the carving and an ideal photo vantage point,” according to the proposals.

Additionally, the changes would include renaming the park’s Confederate Hall Historical and Environmental Education Center to “Heritage Hall,” revising the association’s logo to remove a depiction of the carving and building a new chapel on the mountain’s summit.

Support for adopting changes to how the park’s Confederate symbols are presented has been bolstered by the association’s new board leader, Rev. Abraham Mosley, who was tapped last month as the association’s first Black chairman.

“If these things are approved, we’re going with them,” Mosley said after last month’s meeting. “I want to see the whole story told. History is history. There’s the good, bad and the ugly.”

Critics and racial-justice advocates have long highlighted the carving’s origins as part of a push to erect Confederate monuments across the South during the Jim Crow era of segregation, when backers sought to promote the “Lost Cause” narrative of the Civil War and sweep away the influence of Reconstruction.

Early ideas for the carving came shortly before the Klan’s 1915 gathering on the mountain in which the hate group burned a large cross and formally launched its second founding, according to Todd Groce, president and CEO of the Georgia Historical Society.

The carving faced decades of delays until the 1954 landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education to outlaw separate-but-equal policies and desegregate schools sparked renewed interest in its completion, Groce said. The carving was finished in 1972.

“It’s part of a massive resistance at that point to desegregation,” Groce said in a recent interview. “There’s nothing related to Civil War history that happened there. … It’s really more about that Jim Crow era.”

Momentum to remove the carving has built in the years since a mass shooting at an African Methodist Episcopal church in Charleston, S.C., committed by a white gunman in 2015, followed by a wave of protests to take down Confederate statues and other symbols in several states across the South.

More than 100 Confederate monuments remained standing in cities and towns across Georgia as of 2019, according to tracking by the nonprofit advocacy group Southern Policy Law Center. A handful have been removed in the years since the Charleston church shooting.

Supporters of the carving’s removal face an uphill battle due to legislation Gov. Brian Kemp signed in 2019 that bans altering or relocating Confederate monuments on property owned by the state, including Stone Mountain. New legislation introduced by state Rep. Billy Mitchell, D-Stone Mountain, aims to repeal that law.

“Today is a time to act on the proposals that have been made and to go further,” Mitchell said at the April 26 meeting. “Those who do not learn from their history are doomed to repeat it. … [And] those who learn from their history and don’t make amends to the errors are just doomed.”

Meanwhile, opponents of changing the carving or adding educational context have dismissed the proposals, calling them attempts to erase history and the pride many Southerners take in their homes and heritage despite the old wounds of slavery, racism and war.

“Stone Mountain park by law is a memorial to the Confederacy,” said Martin O’Toole, a Marietta attorney and spokesman for the Sons of Confederate Veterans’ Georgia chapter. “It’s not the purpose to contextualize it. It’s not the purpose to talk about the Ku Klux Klan or other things like this.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Capitol Beat News Service.