Section Branding

Header Content

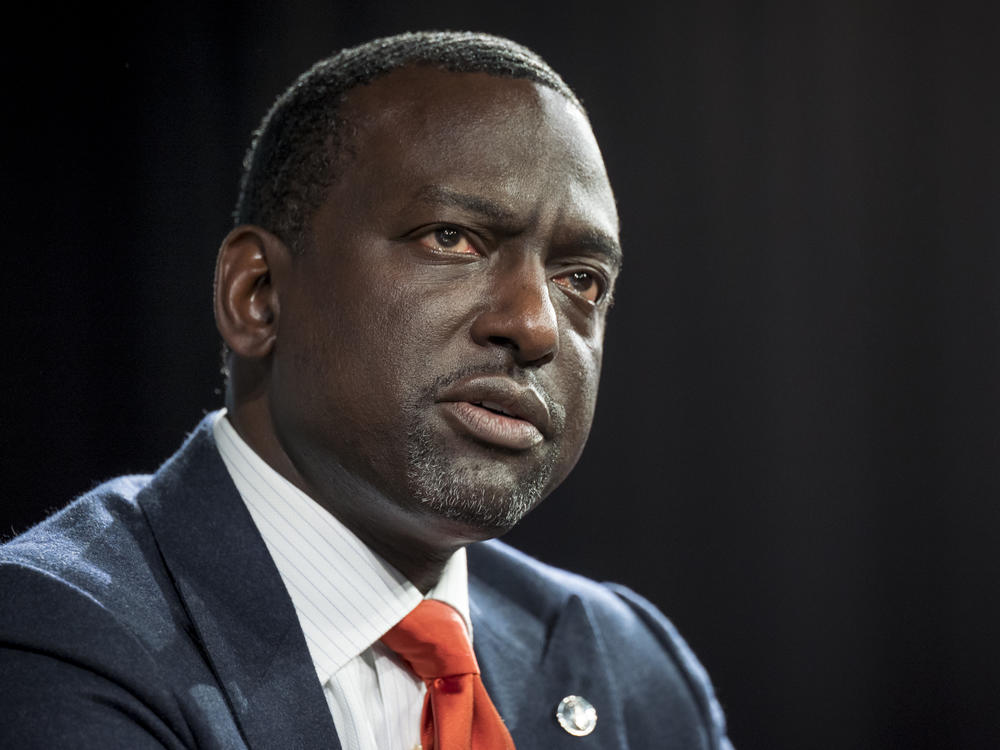

Central Park 'Exonerated 5' Member Reflects On Freedom And Forgiveness

Primary Content

In 1989, 15-year-old Yusef Salaam was one of five Black and Latino teenagers who were wrongly accused of assault and rape in the so-called Central Park jogger case.

At the time of his 1990 trial, Salaam, then out on bail, felt confident that the truth would come out and that he and the other teens would be proven innocent.

"I was on the phone with a friend of mine and I remember someone running up to me, [saying] 'They got the verdict! They got the verdict!' " Salaam says. "And I told the person, 'Hey, they got the verdict. I'll see you in a little while. I'll be right back. I'll be home.' And I didn't come back until seven years later."

Each of the boys, then known as the "Central Park Five," was convicted. It wasn't until 2002 — well after Salaam had completed his nearly seven-year prison sentence — that DNA evidence confirmed that they were all innocent. A serial rapist and murderer had acted alone in committing the crime.

"When the truth came out, that's when we got our lives back," Salaam says. "But for those of us who had five to 10 years prison sentences, we had done all of someone else's time. ... We will never know what our life would have been like had we not gone through this horrible experience."

Salaam now refers to himself, Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana and Korey Wise as the Exonerated Five. Their stories were told in a 2012 documentary by Ken Burns and in the 2019 Netflix series When They See Us, directed by Ava DuVernay.

In the memoir, Better, Not Bitter, Salaam reflects on his wrongful conviction and his efforts to forgive those responsible for his vilification.

"You have to be able to forgive so that you can cut yourself from the ball and chain that's holding you back," he says. "It has nothing to do with the individual who harmed you, but everything to do with yourself."

Interview highlights

On how the boys were forced to give false confessions

I remember when I was [at the precinct] with Korey [Wise] hearing him getting beat up in the next room. I remember hearing him yell out, "OK, OK, I'll tell you!" And he made, if I'm not mistaken, four completely different confessions, four completely different ones. And the one that he implicated me in, they played at my trial and all we wanted to do was go home. This was a nightmare. We were delirious with hunger. We were delirious, because time was passing and we didn't know what time it was, just a whole nightmare of the whole situation and I think what happened is, after a certain point, you break and in the breaking point, you say anything that will allow you to get out of that.

On the advice his mother gave him — which led him to not initially agree to the police's narrative

[My mother] told me something that's very important. And I think that the thing that she told me is something that I tell people often. She said to me, "Stop talking to them." And then she said to me, "They need you to participate in whatever it is that they're trying to do. Do not participate. Refuse." And for me, it was one of the most powerful learning tools that I could ever imagine, because here I was on my own, being told to stand my ground and being told in many ways that it's on me. "I can't come into the room with you. I can't fight for you. You have to fight for yourself. But I need you to know that whatever you do, they're trying to get you to participate in your own destruction."

On being in danger in prison because of how high profile his case was

I think all throughout our case, there was a knowledge of who we were. It was very difficult for us to hide. I'm saying "hide," because we wanted to be anonymous, but we had been convicted of this heinous crime. We have been vilified in the media. Over 400 articles [were] written about us within the first few weeks. And our faces were on every single front page of every newspaper in New York City for a very, very long time. So by the time we got to prison, the inmates had already known who we were. ...

You're told the worst crime that you can go to prison for is rape. The only crime that trumps rape is child molestation. And then you feel all of the tension, all of the negative [energy] ... you feel that, and you're walking through that in these prisons and here are killers around you. Here are [rapists] around you. Here are child molesters around you, and they want justice. They want to do to you what you have been convicted of.

On his feelings toward the police and prosecutors who put him behind bars

The overwhelming feeling that I have towards the police and prosecutors is that they knew that we had not done this crime. They knew it, but yet they chose to move forward. They built their careers off of our backs, and the law of karma caught up to them. And they never imagined that they would have to contend with these crimes that they committed — because these are crimes. They're supposed to be the upholders of law and they have things like prosecutorial immunity. But they were involved in prosecutorial misconduct. No one wants to be in a situation where the people at the highest level in life are the ones who are the most criminal. We want those people to be the most upstanding. They have to hold that truth in their minds and hearts as they move in the justice system because they're changing people's lives. ... The people who are supposed to uphold the law, it is criminal when they do the exact opposite of that.

On his healing journey

We've been able to make leaps and bounds in our healing, in our adjustments into society, but at the same time, it's still there lurking in the background. The awful experience that we should have never gone through is really always the cloud over our heads. But the cool thing about it is that we now know how to deal with those emotions. We now can say, "This is how you get through any prison that you may be going through," whether you're physically in bondage or not. Making the choices that are meaningful, taking the time to breathe, meditating, creating vision boards, all of those things are necessary.

They say the imagination is the precursor of what's to come, and so if you can imagine a future that is brighter than the one that you're growing through — and I'm saying "growing through" on purpose, because when you get to that point, you realize that you're not just going through something, but that you're being prepared for greatness, that you need to know the lows in order to appreciate the highs in life. I think that when I look at my story, being able to look at it from the outside gives me the tremendous opportunity to describe in full what it is that I had gone through, and then going back in and being a participant in my growth and development is important because you have to marry those two things together. And it's that that causes you to step forward with tremendous hope in the future, with tremendous faith in the future, knowing that it can only get better and not get worse.

Sam Briger and Thea Chaloner produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the Web.

Copyright 2021 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.

Bottom Content