Section Branding

Header Content

A Path To Peace: How A Former Navy Corpsman Honors His Fallen Friends On Memorial Day

Primary Content

Ralph "AK" Angkiangco enlisted in the Navy in April 2008 one year after graduating high school. He was an 18-year-old kid uncertain about what he wanted in life, apart from fleeing his parent's place in San Diego. He had initially considered joining the Marine Corps, but with America's Global War on Terror in full swing, his father persuaded him to become a hospital corpsman in the Navy instead.

A medical career, his father argued, would provide him the opportunity to get an education while serving alongside Marines in combat. And AK didn't fantasize about firefights or a chest weighted down by medals, ribbons and awards—each complete with a story of grandeur and heroism—so he took his father's advice.

The Navy trains its corpsmen at Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston in Texas. It was there that AK learned the basics of combat medicine. Instructors taught him how to treat and prevent infections in the field, splint a broken bone and how to stop an arterial bleed.

But there are some things that cannot be learned in a classroom.

"We were told that as a corpsman you will save lives. There's no ifs, ands or buts," AK said. "But the fact that obviously you can't save all lives, they don't really go over that or explain that. I had to figure that out on my own."

Each year, Memorial Day brings that home. For AK - who measured his success by the number of lives saved - it's a reminder that his best wasn't good enough.

The new corpsman deployed to one of Afghanistan's harshest battle spaces

When AK joined 1st Battalion 3rd Marine Regiment—an infantry unit out of Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii—he nonchalantly fell into his place. Five days a week AK showed up to work, where he often taught the Marines of Bravo Company's 3rd Platoon basic life-saving techniques.

Other days AK administered vaccines or knocked out paperwork. It wasn't immediately apparent to the young corpsman just how important his role would be.

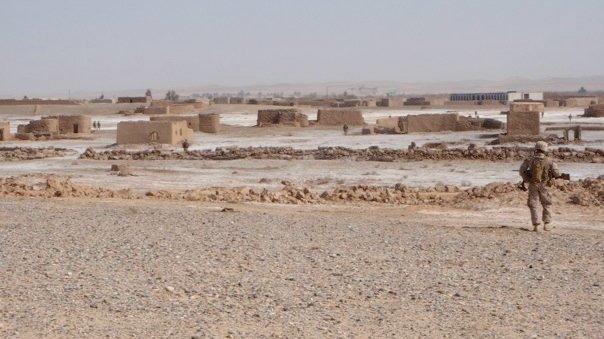

But then he deployed to Afghanistan for the first time, to Helmand province, one of the country's most fought-over regions.

A portion of the Bravo Marines were based at a small outpost, dubbed ManBearPig, a shipping container retrofitted into a command center that housed a handful of radios and maps. A guard tower in the center of the post stood maybe 20 feet tall with room enough for two; a bunker covered with sandbags doubled as a sleeping quarters for some; two stationary Humvees with automatic weapons provided fire support to the north and west.

ManBearPig was the westernmost post in the battle space. Everything to the west belonged to the Taliban, who made their presence known by frequently firing upon Marines returning to base at the tail end of a patrol. One thing was for certain: they were watching.

AK was the corpsman for 3rd Platoon's 1st squad, a close-knit group of Marines just over a dozen in size with Sgt. Steven Habon at the lead. The sergeant was a Fallujah veteran, and his time spent clearing house-to-house in one of the bloodiest battles in recent memory instilled in him a rigid sense of responsibility for the lives of his men.

To say that he was hard on his squad is an understatement. Before every patrol, Habon had the Marines clean their weapons. After every patrol, they cleaned their weapons. Every Marine under his command had to be capable of filling every and any position. Everyone, including AK, had to know how the radios worked, how to operate each weapons system, how to call for support and how to save a life. The success of the mission and the safety of the group should never hinge on any one person, he said.

"I think he did that because he cared for us, obviously," AK said. "He just wants us to have all the possible tools at our disposal. If s*** ever happened to us, God forbid, you know, that maybe he can rely on all of us to step up."

An early afternoon patrol takes a life

In the early afternoon hours of Jan. 10, 2010, Habon and his squad made their way west as they had done dozens of times before. And like many of their previous patrols, they took fire as they began making their way back to base.

The landscape resembled parts of America's Midwest, farmland lined with irrigation canals that compelled the Marines to walk along small, narrow berms that ran along the edge of the fields. This limited the number of routes the Marines could take outbound on patrols as well as ways to return home. For this reason, the Marines routinely switched up their routes and never took the same path twice on the same patrol.

As they returned to base, Lance Cpl. Jacob "Slim" Meinert was on point. AK fell in line behind Slim as they led the patrol back, slowly making their way home while taking cover in a dried irrigation canal, one step at a time.

AK was only a handful of meters behind Slim when the young Marine stepped on a pressure plate, detonating a hidden bomb beneath his feet. The blast launched him as high at 15 feet, clear out of the canal, AK explained. The pressure knocked AK backwards, stunning him for a moment before the gravity of the situation set in.

"Don't move!" Habon yelled.

But AK couldn't hear him; his ears were ringing, he was disoriented.

He looked to his right and saw Slim on the ground. Without hesitation AK crawled out of the canal, heart thumping in his chest, his feet desperately searching for stable terrain as he sprinted toward the downed Marine.

Slim was alive, but the explosion had severed multiple limbs. He was bleeding to death.

"Why me?" Slim repeatedly called out.

"I got you, you're going to be fine," AK responded, trying to reassure his friend as he worked.

He fastened a tourniquet on Slim's upper thigh to stop the bleeding from a missing leg. AK determined the Marine had a collapsed lung, so he inserted a needle between the ribs to release the pressure. He was on autopilot, doing his best to remain calm while frantically fighting to save his friend.

AK was alone. Habon had told his squad not to move because more often than not, the Taliban place a secondary charge nearby, in hopes the Marines will rush in to aid the wounded and take more casualties. Every step between the Marines and AK had to be carefully placed, one painstakingly slow step at a time, as they swept for additional traps.

Eventually, two more corpsman came to AK's aid before the casualty evacuation arrived. It had been maybe 30 minutes since the blast when the helicopter finally touched down.

Slim was loaded up and the Marines watched as the aircraft slowly disappeared from sight, the sounds of the rotors gradually fading away. AK stood up, exhausted, trying to make sense of what had just happened. The patrol made its way back to base, the Marines walking in silence, alone with their thoughts.

Shortly after they got back, AK was told that Slim made it all the way to the field hospital, but he died on the operating table.

That was 10 years ago.

The pain of loss can be pushed aside for only so long

Seldom does a day go by that AK doesn't question whether he did everything he could, whether he did it right, or did it wrong.

After returning home from Afghanistan, AK began drinking excessively. He and the Marines went out to the bars to celebrate their return home, but that celebration, AK explained, never seemed to stop. And it wasn't just him, it seemed like it was the entire battalion. Drinking to forget, disguised as "having a good time."

When it came time for his post-deployment health assessment, designed to gauge an individual's physical and mental health following time overseas, AK lied. Instead of admitting that he had developed a drinking problem, suffered ongoing feelings of self-doubt, that he needed help, AK gave the textbook answers he knew would allow him to continue working alongside his friends.

Looking back on it now, he admits that had he been honest, things might have turned out differently.

"I probably would have gotten some help or actual treatment for it and maybe my career might've hit a roadblock because of it, because being put on [limited duty] for that, we all know is just, horrible for your [evaluations]," AK said. "But I might've, probably been put in a better place mentally from there on out, at least have tools for me to decompress rather than alcohol, and learn about what I have rather than ignore it for like, I don't even know, six or seven years."

But like many of his peers, he didn't seek help. Rather, he chose to carry his guilt and afflictions alone. Furthermore, he began distancing himself. He got it in his head that Marines around him would die, and to avoid more pain, he put up a wall so he wouldn't get close to anyone. Even family was kept at one arm's distance.

He spent the next five years bouncing from one duty station to the next, from Hawaii to San Diego and then to Twentynine Palms in the California desert. AK continued putting his problems on the back burner, kicking the can down the road year after year until a neglected training injury to his ACL forced him to return home halfway through a deployment to Kuwait in early 2016.

AK was barely mobile following his reconstructive surgery, so his parents brought him home to recover after he was discharged from the hospital. But after a few short weeks he had to return to base and the barracks. The building was typically bustling with activity, but everyone was still on deployment, and once again, AK found himself alone.

Back at base he fell into a self-destructive routine. AK would wake up, play video games, eat some chow, more video games, start drinking, attend his physical therapy appointment then crutch back to his room where he continued drinking until he eventually passed out.

Repeat five days a week for two months.

Broken glass breaks the downward spiral

The thing about mental health, AK explained, is that issues always make their way to the surface. Not a matter of if, but when. One night, in a drunken fit, AK started throwing glass bottles into the street from the barracks.

He said he doesn't remember exactly why he did what he did, but he does remember getting in trouble for it the next day because it was the first time someone had checked in on him in over a month.

"I just broke down crying because that was like the first time anyone really asked me what was going on, you know what I mean? Like, just a simple question, 'what's going on?' " AK explained.

He was ordered to see a mental health specialist once a week. He was also prescribed Valium, but it didn't help much. Side effects can include depression, thoughts of suicide, confusion, trouble sleeping and irritability, to name a few. It also doesn't mix well with alcohol.

Just over one month later AK checked into his new duty station at the hospital unit at Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center Twentynine Palms. He didn't make it through the end of his first day before he found himself in trouble again. While working on a computer he became frustrated and as a result said he was going to burn the building down. AK said he said it to himself, more or less under his breath, but someone had overheard and reported him.

"I just told them everything: 'I'm having flashbacks, I'm hearing things, seeing things,' " he said. "Everything around my life was just not working."

AK was treated twice for PTSD before he finally left the Navy in January 2017. But he wasn't cured; that's not how it works. Instead, he spent months working with specialists that equipped him with the tools he needed to learn to live with it.

The former corpsman becomes a different kind of healer

This spring AK will graduate from Point Loma Nazarene University in San Diego with a bachelor's degree in social work. He was recently accepted to Columbia University for his master's. He chose to pursue a career in social work because he wants to help other veterans who are struggling as he once did.

Memorial Day is still painful, and he says to some degree it will more than likely always be that way. AK still harbors guilt for Slim's death, even though he knows it's not his fault. But he doesn't drink himself into oblivion to make it through the holiday weekend anymore.

And that's a good place to start, working to find ways to celebrate the lives of friends lost.

This year AK plans to spend Memorial Day with Habon and another Marine from his time in Bravo Company. The three of them live in Southern California these days and make serious efforts to see each other often. When they get together they catch up about their lives' latest twists and turns. Sometimes they reminisce about their time in Afghanistan, about Slim and the other Marines come and gone.

"It's still difficult, but I'm going into it with a positive mindset, at least that's what I'm telling myself....'cause there's no justice in getting [blacked out] for them, because the whole point of the day is to remember, and not drink to forget," AK said.

"I just kept thinking more on what they would have wanted, if they were able to tell me."

Former Cpl. Dustin Jones served with Bravo Company, 3rd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment, with Ralph "AK" Angkiangco.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.