Caption

After the difficulties of this year, support for students has never been more crucial.

Credit: Drazen Zigic/Shutterstock

|Updated: June 8, 2021 3:07 PM

After the difficulties of this year, support for students has never been more crucial.

Wendy Mallis was proud to be the first person in her family to go to college, but she never expected that she would also be the first to complete her master’s degree during a global pandemic.

Mallis is graduating in May with a Master of Education in school counseling from Georgia State University. She was interning at an elementary school when a shift in everything altered her path.

“When I got into my program, none of this pandemic stuff had started yet,” Mallis said. “I was expecting to be in a school meeting with students, helping them with their challenges. You’d have a kid come into your office with this problem, and you’ve got to help them figure it out.”

Everything Mallis does now is virtual, but she’s still helping students with the same problems in new ways. It’s harder to get a hold of students when she can’t be in the building with them, but she tries to ensure they still feel supported.

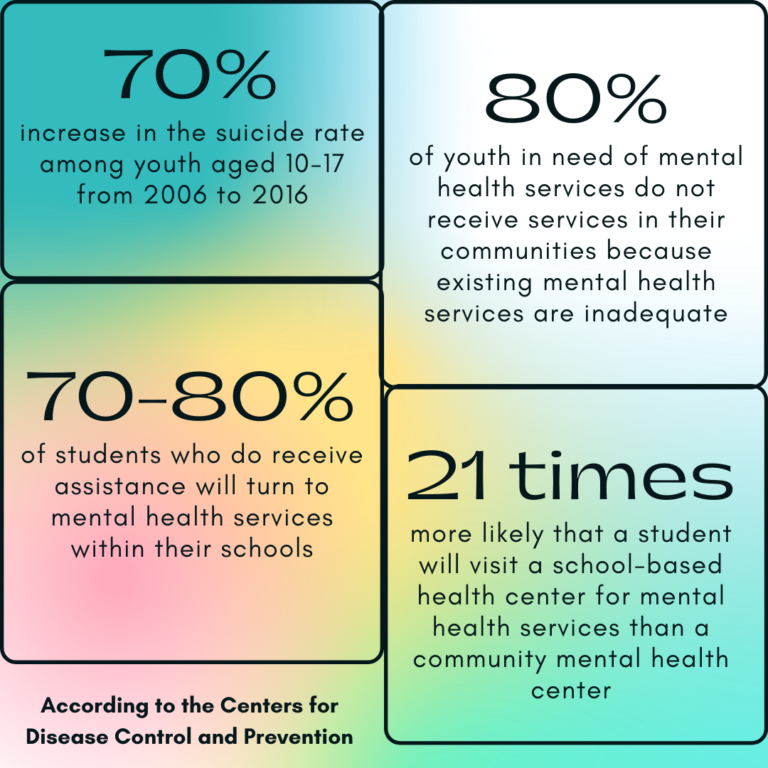

And after the difficulties of this year, support for students has never been more crucial. According to the Centers for Disease Control, students are 21 times more likely to visit school-based centers for mental health services for treatment rather than community mental health centers. So counselors will most likely be the first to see youth who are the most in need.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, students are 21 times more likely to visit school-based centers for mental health services for treatment rather than community mental health centers.

Most students in K-12 and college have felt some lack of support this year as a result of increased isolation. For Mallis, working through lessons without the company of her classmates was difficult. She and her campus colleagues have learned to stick together virtually, with online chat groups that help them feel connected.

While the shift to online learning was an unanticipated challenge, Mallis said she is ready for the potential new realities of the field.

“I feel prepared in a different way than maybe I thought I would,” she said. “I still feel prepared to go out and do the job as you would an in-person school. But I also feel prepared for the future of how things are going to be. Not everything is going to go quite back to normal, maybe not for a while. Students’ parents are still going to have the option to keep them online in some cases. So I feel kind of prepared to deal with that situation, too.”

Innovative teaching strategies could very well become a cornerstone of curriculum going forward, especially in regaining ground that has been lost. Dr. Stacy Delacruz said repairing the educational damage of this year will not be a quick fix. She’s an Associate Professor of Early Childhood Education at Kennesaw State University, and her research involves digital literacy in kindergarten through fifth grade classrooms.

“The research has shown a lot about when you transition to remote learning, that there’s an inequity because some students, particularly in poverty, don’t have reliable access to the internet or devices,” Delacruz said. “And so that could have left some students behind for sure.”

While gains that were lost this year will have a lasting effect, she’s confident that teachers and counselors will get back in schools and turn things around. For her, the pandemic has emphasized the idea that good teaching is constant innovation, which is something she instills in her own students.

Delacruz said she is better prepared to take on the shifting modalities of pandemic learning with her background in digital literacy, but learning from other teachers has helped her find new ways to teach her students to teach the next generation.

Mallis said she is ready to guide the next generation, but virtual school and work combined with the inability to see family and friends has made it difficult to maintain a balance between work and downtime.

“I know there’s a set time for the school day, but even then, students and parents are still emailing their questions whenever they think of them,” Mallis said. “Parents get off work and they have questions, they want to talk, which is totally valid because I know parents have to go to work too.”

But ultimately, she said, this work is rewarding. While she doesn’t always know if her impact is the same online, she’s inspired by students who go out of their way to thank her for what she does.

“I had a student that was just really excited to tell me that she got into college, because I had helped her fill out the application,” Mallis said. “And that was just one moment when I was really excited, it felt like my hard work was paying off. It just meant a lot that she took the time to be like, ‘Hey, I got into this college. Thanks so much for helping me.’”

As Mallis starts the job hunting process, she says she sees some light at the end of the pandemic’s dark tunnel. She’s open to positions that are both in-person and virtual, and she’s stepping into a field that needs her now, maybe more than ever.

While Mallis is eager to be back with students soon, she’s not sure that it will ever truly be the same.

“I guess I am not convinced things are going to go back to the way that they were necessarily,” Mallis said. “But maybe it’s a good thing. If people just try to care about each other a little bit more, maybe it’s not such a bad thing.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Fresh Take Georgia.