Section Branding

Header Content

FDA Poised For Decision On Controversial Alzheimer's Drug

Primary Content

A drug called aducanumab could become the first approved treatment designed to alter the course of Alzheimer's disease rather than relieve symptoms.

But it's unclear whether the Food and Drug Administration will approve the drug because of persistent questions about its effectiveness.

The FDA has a Monday deadline to make a decision on what would be the first new Alzheimer's drug in nearly two decades.

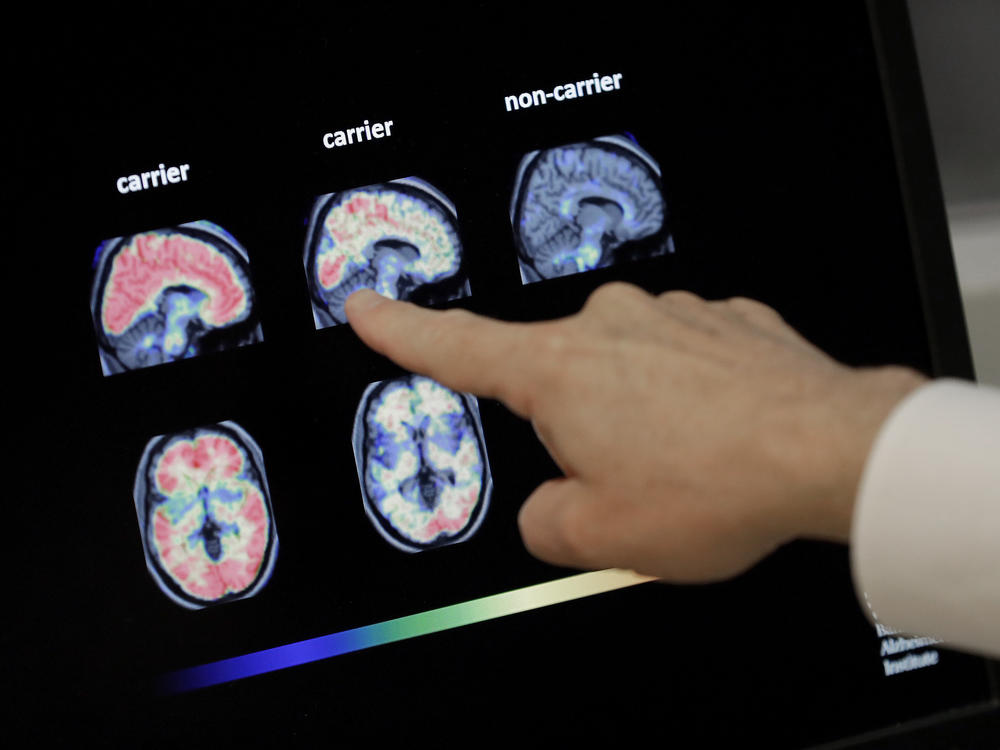

Aducanumab, which the drug companies Biogen and Eisai are developing, is designed to reduce the sticky amyloid plaques that build up in the brains of people with Alzheimer's. And studies show that it does that well.

What's unclear is whether reducing plaque slows down the disease process that ultimately kills brain cells and impairs memory and thinking.

Before aducanumab, a long list of anti-amyloid drugs had failed to help patients despite reducing plaques. And aducanumab appeared to be a failure just a couple of years ago.

In 2019, Biogen and Eisai ended two major studies of the drug after preliminary results suggested it didn't work. Then a reanalysis of the data produced a more favorable result, and the companies decided to seek FDA approval after all.

Ultimately, the FDA was presented with one study showing the drug worked and another showing it didn't.

Even so, many patient-focused Alzheimer's groups support approval of the drug.

"We believe strongly that if the FDA approves this treatment, it will be a new day for Alzheimer's," says Harry Johns, president and CEO of the Alzheimer's Association.

The Alzheimer's Association backs approval of aducanumab even though studies show the drug has, at best, a modest ability to slow down the disease.

"This is not a cure," Johns says. "This is an incremental benefit, potentially, and that benefit can be very real in changing lives for so many."

A panel of scientists who advise the FDA saw it differently. In November, the panel voted against approval, saying the drug failed to meet the usual scientific standard of two positive studies.

But Johns says the panel took a narrow view, one that discounted the roughly 6 million people in the U.S. who have Alzheimer's.

"Scientific approaches that do not take into account the full science or the great need of the community that is affected today [are] not pro-patient."

Proponents of FDA approval argue that people in the aducanumab studies who got a higher dose of the drug did benefit.

But scientists who oppose approval say Biogen and Eisai need to conduct another large study to prove that the higher dose really works.

"The data just aren't there right now to say that this is the drug to open up the new era for the treatment of Alzheimer's," says Dr. Jason Karlawish, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and co-director of the Penn Memory Center.

Also, aducanumab can have side effects, including bleeding and swelling in the brain, Karlawish says, which means people taking the drug will need regular brain scans.

"The uncertainty of whether it actually has a benefit means we would be introducing into practice a drug that does have risks," Karlawish says, "and yet very well [may not be] benefiting the patients who are taking it."

The uncertainty around aducanumab could mean a difficult decision for people with Alzheimer's and their families.

"If this drug is approved and people are considering taking it, they need to be aware that it's quite possible that it does not work," says Dr. David Rind, chief medical officer of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, an independent nonprofit research organization that studies medical treatments.

FDA approval of aducanumab also could lead to greenlighting other Alzheimer's drugs whose efficacy is unproved, Rind says.

"You could imagine a situation in which additional therapies are then, instead of being compared with placebo, would be compared with aducanumab," he says. "Does that mean it works, or it doesn't work?"

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.