Caption

Shemekia Copeland performs at the JusticeAid Benefit Concert for Justice For Vets at the Warner Theatre on Sunday, Sept. 14, 2014, in Washington, D.C.

Credit: Paul Morigi/AP Images for NADCP

It was 1979 when then-President Jimmy Carter introduced the country's first ever observance of Black Music Month. The month was established to recognize the economic and cultural power of Black music, as well as those who make and promote it.

The month was later renamed African-American Music Appreciation Month under President Barack Obama.

GPB’s Leah Fleming recently spoke with Tammy Kernodle, a professor of musicology at Miami University in Ohio, to dig deeper into the roots of the month.

Tammy Kernodle: When you think of 1978, 1979, most historians will tell you that the Black Power movement was really dying down. Either through violence, mass incarceration, or people assimilating and becoming disillusioned. But what we forget is that the Black Power and the Black Nationalist movement were not just about radical activism. It was also about reclaiming and establishing an understanding of our cultural heritage. But there was also an economic piece to that. Black Power was about Black people empowering themselves and creating infrastructures. And that's the important part: infrastructures that would galvanize our communities culturally, economically, politically and socially.

Leah Fleming: So when President Carter at the time in 1979 rolled out the first Black Music Month, he talked about growing up in Georgia and hearing many Georgia artists and hearing the pain that came through the music and the movement, and hearing about some of the joy of being Black. We heard that then. We continue to hear that now.

Tammy Kernodle: Well, I think that's what makes Black music such an important cultural artifact, is how it encapsulates the fullness of life. It has been one of the chief documenters of our experience. And we see that in this current age, I think in a way that became absent in the decades that followed the establishment of Black Music Month, because at the time that this month of appreciation was established, we were at a high point of Black music and Black consciousness in a wedding of those things. And I think what we saw with the kind of corporate takeover of Black music in the '80s, you know, with all of those labels like Stax, like Motown, and Atlantic and all of those indie labels that are giving us all of that music, that was the soundtrack to our liberation struggle throughout the '50s, '60s and '70s. You know, when CBS and Sony and MCA and all of these labels took it over, we saw the muting of certain narratives within our music. Now they are reemerging. They're reemerging because you have a generation of artists who have found new ways in which to engage.

Leah Fleming: So what are you listening to this Black Music Month?

Shemekia Copeland performs at the JusticeAid Benefit Concert for Justice For Vets at the Warner Theatre on Sunday, Sept. 14, 2014, in Washington, D.C.

Tammy Kernodle: Oh, I'm listening to everything because I consume music. So, like, for the last couple of days, I've been listening to Shemekia Copeland, you know, who is a blues singer, she kind of does Americana. She has an album called Uncivil War. So what's really resonating with me is how we're seeing these protest narratives, these social message songs all showing up in these genres that don't get played primarily on Black radio these days. But, you know, it's getting played on white radio and in regional spaces where this is a Black woman engaging in a conversation with white America in many ways. So I listen to a range of things. Classical music, you know, because that's something we have to talk about in Black Music Month, because we oftentimes want to center Black Music Month around R&B and gospel and, you know, hip hop, because we think of those things as being representative of authentic Blackness. But classical music, we have classical composers like Courtney Bryan and Mark Lomax, who did a suite of albums called the 400 African Suite that really tries to musically trace us from 1619 to a future that he envisions. I'm looking at how Blackness is intersected in sound in so many different ways. So I listen to so many different things, and I'm an old-school person, so I've got thousands of CDs and LPs.

Leah Fleming: You say that the month should not be maybe African-American Music Appreciation Month. It should've remained Black Music Month.

Tammy Kernodle: Yes, ma'am. Blackness is, the term Black is representative of the wholeness of identity. We are African people at our core. But we did not just come to America. And to say African-American means that you negate all the Black people and all the Black music that came out of the Caribbean and South America, out of Canada, out of London, out of Germany. Black people extended from the continent, not just through slavery, but migration and colonization. And we created a larger diaspora of expressions and experiences. And that music is a reflection of those environments. And we hear some of those things coming into African-American music. But when we use the term African-American music, it means that we are very U.S.-centric. We are cutting off what are these larger cultural connections of sound and culture and experience that are represented under Blackness.

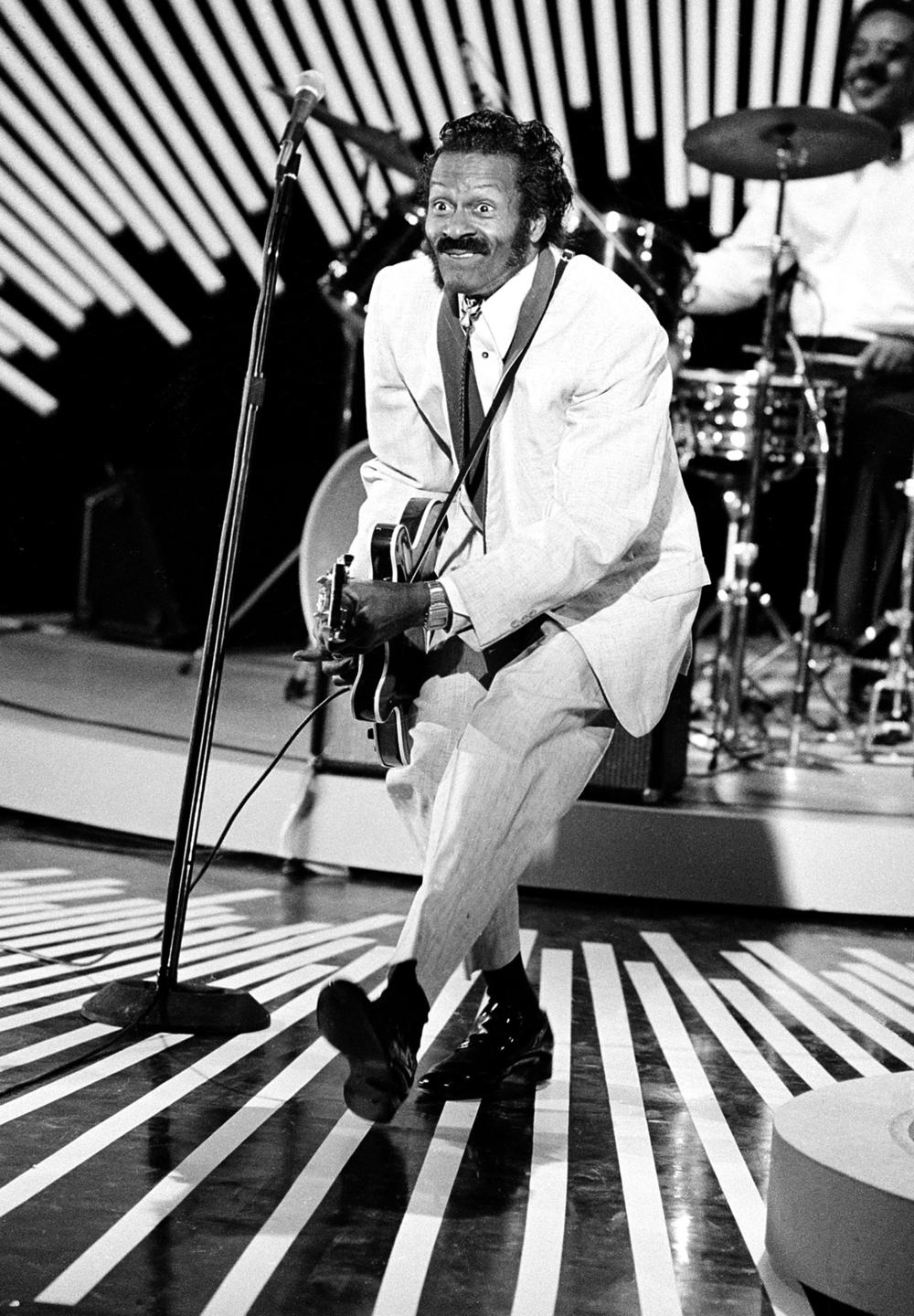

Leah Fleming: So I want to ask you one more question. Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Bo Diddley: They're all considered the originators of rock 'n' roll. But that's a fact that few people are aware of, especially today. So how do you suggest we not only appreciate, but hold on to the history?

American guitarist and singer Chuck Berry performs his "duck walk" on stage as he plays his guitar on April 4, 1980. The location is not known.

Tammy Kernodle: Well, I think, first of all, what you are doing here is important, because NPR, public radio has become one of the primary mediums that is above all of the political fray and rhetoric and bringing to us wholesome stories. So I thank you for your work in that. But I think also, as we are seeing these conversations about critical race theory and what is taught in the classroom, what we need to understand is how music can be a focal point for us to understand these particular moments and the importance of these voices. Right. And so it's about reclaiming that. And what I liked about the initial vision of Black Music Month, that that initial vision was about preserving, it was about progressing, but it was about historicizing. And too often we leave out the history. Every generation thinks that they are charting a revolution. And they think that because, in many cases, they don't do their history lessons. They don't learn their history. They come back to that, you know. Or they are told, ‘Hey, do you know this?’ or ‘Do you know that?’ And not all artists, but many people who think they're groundbreaking don't understand sometimes these historical trajectories. So I think it's important that we elevate. I think it's important that Black radio elevates these voices. And I think with, you know, the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in D.C., but now the newly minted National Museum of African-American Music in Nashville will see people having much more of an expansive understanding of what has been the history of this music. So this is what I do every day. Every day. I want people to leave, you know, my classrooms hearing music different, but understanding the people behind the music. I tell my students all the time, you cannot like Black music and not have a consciousness about Black people. If you do, something's wrong.