Caption

The state lawmakers who will redraw Georgia’s district lines later this year hold a joint town hall hearing to gather public input June 29, 2021, at South Forsyth High School in Cumming.

Credit: Sherry Liang/GPB

The state lawmakers who will redraw Georgia’s district lines later this year hold a joint town hall hearing to gather public input June 29, 2021, at South Forsyth High School in Cumming.

The Democratic Party appears on the rise in Georgia, with big gains over the past few election cycles, but the GOP still has its hands on the levers of government, and its power brokers will likely do whatever they can to stay in charge.

That’s the situation today as lawmakers travel the state in advance of a to-be-scheduled special session to redraw the state’s Congressional and legislative boundaries for the next decade. But 20 years ago, the shoe was on the other foot, and Democrats were the ones in power and looking to stem the rising tide of the Republican minority.

“Democrats have had a good round of elections on this last round, Republicans were having good rounds going into 2000,” said University of Georgia political science professor Charles Bullock. “But as a minority party, it’s hard to get the gains you have been making in statewide contests and translate that into seats in the General Assembly because as the minority party, you’re going to have maybe ringside seats to watch, but you’re going to be watching, not doing.”

As members of the public weigh in on an unprecedented redistricting cycle, the past two redistricting cycles can offer insight into the coming battle.

Georgia Republicans were feeling their oats heading into the new millennium. Though Democrat Roy Barnes remained in the governor’s mansion and Sens. Max Cleland and Zell Miller were in the Senate, the U.S. House was split 8-3 with a Republican advantage, and the wind was at the GOP’s back in the state Legislature as well, said state Rep. Sharon Cooper.

“Republicans at the time were beginning to pick up more and more seats,” said the Marietta Republican first elected in 1996. “We were gaining steam in a march toward the majority. We weren’t there yet, but we were picking up seats.”

This was not lost on Barnes, who had no desire to deal with a divided government, Bullock said.

“Especially with regard to the state Senate, somewhat less so with regard to the state House, the maps were drawn in the governor’s office rather than by the redistricting committees or by the Georgia reapportionment office,” he said.

When the maps came out, the partisan gerrymandering was clear.

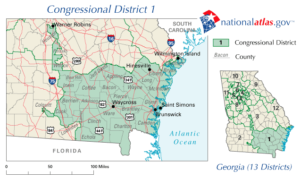

Georgia’s 1st Congressional District as it was from 2002 to 2005. A little finger reaches out from the main body of the district to Saxby Chambliss’ home in Colquitt County.

The state’s 1st Congressional District on the southeast coast, then represented by Republican Jack Kingston of Savannah, grew a tentacle to encompass then-Rep. Saxby Chambliss’ home in Moultrie, pitting the two Republicans against each other in one district.

Chambliss would leave the district to Kingston and get his revenge by defeating Cleland in the 2002 Senate race.

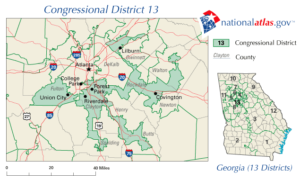

Georgia’s new 13th Congressional District was dubbed by some the “dead cat on the expressway district.”

“It kind of looked like an animal that had been run over many, many times and flattened out,” Bullock said. “The reason had those legs and tail and things reaching out in all directions was tracking down and incorporating into a single district Black concentrations out in Lawrenceville, down in Griffin and various other places.”

The political mischief was just as bad mapping out the state Legislature, where 35 of the 76 GOP House members were paired, or drawn into districts with another lawmaker.

“I don’t think that we knew going in that it was really going to be drawn in such an extreme way,” Cooper said. “I was in leadership, and we, of course, were very concerned, and put up a fuss and threatened to sue and started raising money to pay for a lawsuit.”

The 13th Congressional District in Georgia, sometimes called the “dead cat on the expressway district,” as it was from 2003 to 2005.

The effects of that gerrymandering could be seen in the following election, said Cuffy Sullivan with Fair Districts, a nonpartisan group opposed to gerrymandering.

“After the election in 2002, Republicans increased their statewide share of the vote to a majority but didn’t win even one more seat,” she said. “The GOP House seat share stayed exactly the same. So we can say these maps were not responsive to voters.”

Barnes wasn’t able to carve up the state map to prevent his own loss that year to Sonny Perdue, Georgia’s first Republican governor in 131 years. Perdue won a state Senate seat three times in the 1990s before becoming Republican in 1998, ahead of the party-switching rush that would follow.

After the 2002 election, Republicans challenged the maps in federal court. In 2004, the Supreme Court ruled that the maps were unconstitutional and ordered the state to draw new ones.

Meanwhile, the state Senate had flipped to Republican control after four Democrats switched parties, and the two chambers were unable to come to an agreement on new maps.

“At some point, we said, look, if you will draw maps that give us, like, 84 seats, you know, as we march toward 91 — this is the minority leadership — then we will take the maps as drawn,” Cooper said. “We figured that we could win those seats if the maps were fairly drawn, and the Democrats refused to do it.”

As a result, the federal government sent a judge down to Georgia to draw new maps. When the new boundary lines were in force in 2004, the Republican share of seats increased with the share of votes as one would expect, Sullivan said. But in 2006, the GOP-controlled legislature passed a bill to change eight House districts and keep the court-drawn map everywhere else.

“In the next election, you can see how these small changes work to their advantage,” Sullivan said. “The vote share stayed the same, but the GOP seat share increased by 10.”

The next redistricting cycle came at a high point for Republicans in Georgia. Their dominance in the Legislature was not in question, so they had no need to resort to the kinds of measures Democrats had a decade before, but they still drew maps that gave their party advantages.

“The Republicans were hoping to get a supermajority, so the maps were designed to pick up some seats, but not try to squeeze out everything possible,” Bullock said. “So you look at the maps and they don’t look as extraordinary as some of the maps of the state legislative districts 10 years earlier. They certainly favored Republicans, but they were not trying to pick up every conceivable seat.”

Like the Democrats before them, the Republicans drew maps in a way that increased their power even as their share of the vote shrank.

“Even though the statewide Republican vote share decreased, their seats in the House increased, and after a mid-decade redistricting in 2012, became a super majority with fewer statewide votes,” Sullivan said. “The GOP then passed another midcycle bill in 2015 to hang on to that advantage.”

“We are a nonpartisan organization,” she added. “We can tell you that whoever is in control absolutely puts their thumb on the scale, because they can.”

Longtime state Rep. Carolyn Hugley, a Columbus Democrat, has seen this sausage-making from both angles.

As a Democrat who has served in the House since 1993, Hugley has seen the process play out as both a member of the minority party — as she is now — and as a part of the majority in control.

After the 2010 redistricting, 12 House Democrats were paired in districts with other lawmakers, Hugley said, but she said it happened to eight Republican incumbents, too.

Democrats were also surprised by Republicans ending a decades-long relationship with the University of Georgia’s Carl Vinson Institute of Government and replacing it with a new government office called the Legislative and Congressional Reapportionment Office and hiring an attorney who also served as counsel to the state Republican Party to lead it.

“We were concerned about the same things you hear people talking about now,” she said. “We were concerned about accountability and transparency, and our challenge was to ensure that our members had an opportunity to participate in a nonpartisan way, but when you had the Republican general counsel being the counsel to the reapportionment office, that proved to be difficult.”

Public hearings for this year’s redistricting process are underway across the state right now, but the nitty-gritty work of redrawing district lines will not begin until the new census population data arrives, which is expected to happen by this fall.

In a normal year, that population data arrives in the spring with the map-making underway by now. But the pandemic delayed the nationwide headcount, pushing back the redistricting and reapportionment process.

What happens after the data arrives depends largely on the rules adopted by the GOP-controlled committees steering the process.

Adopting committee rules may sound like bureaucratic tedium, but those guidelines will matter, particularly for anyone on the outside looking in on a process known to be secretive and opaque. No date has been set for each chamber’s committee to meet to adopt the new guidelines.

In a July 15 email, Macon Republican Sen. John F. Kennedy, chair of the Senate Reapportionment Committee, said the committee will adopt guidelines “in the near future.”

Last decade’s guidelines outlined important aspects of the process like limits for public access to documents and the requirements for submitting a proposed or alternative map — something Democrats and outside groups will want to do.

Hugley said these rules of engagement need to be decided before House Democrats can hash out a game plan for the upcoming special session.

“I’m hopeful that the districts will follow the population trends, and conceivably, there should be additional Democratic districts because our state is about 50-50 in terms of our politics — Democrat, Republican,” she said.

Despite major Democratic victories statewide, Republicans last year held off a push to gain control of the state House under the current maps. House Democrats only netted two seats last year when they needed 16.

House Democrats will go into redistricting with their eye on the growing suburbs north of Atlanta, where they have picked off seats in recent elections and where the recent leftward shift in the burbs will make it tougher for Republicans to find GOP-friendly turf.

With demographic trends appearing to favor Georgia Democrats in the near term, Republicans may be tempted to repeat some of the steps Democrats took in 2000, but that may not be the right lesson to take from 2000, Bullock said.

Instead, by taking a moderate approach and sacrificing some seats in areas trending Democratic, Republicans may be able to create a majority that is smaller numerically but more solidly conservative, Bullock said.

“The hope would be that those would be districts that Republicans could hold through the 2030 elections,” he said. “So it’s possible that they could come out with maps in which Democrats actually make some gains.”

For now, Democrats can do little more than hope whatever comes out of the committee is relatively fair.

“Whoever has the crayon gets to draw the rules and the way these maps are going to look. That’s not lost on me,” said House Minority Leader James Beverly, a Macon Democrat. “But we would hope that the public would weigh in in such a way that we sort of tilt it toward fairness and justice.”

If not, they may take a page from the Republican playbook after 2000 and take the matter to court, he added.

“If it doesn’t, I think we have redress in the courts,” he said. “Hopefully, we don’t have to get there, and they’ll embrace their better angels.”

Deputy Director Jill Nolin contributed to this report.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Georgia Recorder.