Caption

Atlanta City Council member and mayoral candidate Antonio Brown has lagged in fundraising despite big spending on his campaign..

Credit: Antonio Brown

Atlanta City Council member and mayoral candidate Antonio Brown has lagged in fundraising despite big spending on his campaign..

A belated campaign finance report filed by Atlanta mayoral candidate Antonio Brown shows he spent hundreds of thousands on campaign expenses while raising little money from July through September.

The report includes nearly $300,000 in expenditures on fundraising and other campaign costs. It also shows Brown took in less than $69,000, far less than the four other top contenders in the race, each of whom raised between $450,000 and $1.7 million in the same period.

Overall, Brown, an Atlanta City Councilman serving the city’s Westside District 3, has raised about $378,000 since the start of his campaign in May. The other leading candidates have so far topped more than a million dollars each in contributions.

Brown, who has been under federal indictment on multiple counts of fraud since July 2020 for allegedly lying about income on credit card and loan applications, has acknowledged his campaign’s shortcomings in bringing in money.

“We’ve struggled with fundraising from the beginning of this campaign,” Brown told reporters earlier this month. “I have nothing to hide.”

He has proclaimed his innocence of the federal charges.

Brown’s campaign filed its most recent campaign finance report on Oct. 19, 12 days after the Oct. 7 deadline. Brown told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution the report had been submitted on time, and told the Georgia News Lab on Oct. 12, that the Atlanta municipal clerk’s office was “going to let us know why it hasn’t shown up yet” on the city’s campaign finance portal.

But Municipal Clerk Foris Webb said in an email to the News Lab later that day, that Brown’s campaign had neither contacted his office nor submitted the report.

That evening, following a mayoral debate, Brown told a group of reporters that there had been “miscommunication” about the report being filed due to a death in the family of his finance director.

“I didn’t want to speak publicly about it until I was able to get permission from him,” Brown said. “It’s caused a huge delay.”

Brown’s finance director, Lance T. Jones, told the News Lab on Oct. 25 that there had not been a death in his family, although he had just gotten out of the hospital after a five-day stay.

Brown did not respond to a request for comment.

The News Lab reported earlier this month that Brown had not filed a personal financial disclosure statement that was due by July 1.

Brown told the News Lab in early October that the filing requirement had probably been overlooked. “I didn't even know we hadn't filed one yet,” Brown said.

At the time of publication, Atlanta’s campaign finance portal did not show the report had been filed.

Atypical fundraising yields little return

Of the roughly $69,000 Brown raised in the most recent reporting period, more than $35,000 came in the form of contributions of $100 or less, for which campaigns do not have to disclose donor information such as name, address and employer.

Brown took in nearly $18,000 in contributions of more than $100, including a maximum $2,800 contribution form actress Naturi Naughton of the TV show Queens.

Brown also personally loaned his campaign $15,000.

The report shows Brown, the former head of several now-defunct businesses and nonprofit organizations, used unconventional firms for some campaign work.

To set up his nonprofit campaign committee, for example, Brown paid $5,000 to attorneys who focus primarily on business and corporate law and promote themselves as “the top boutique law firm for entrepreneurs and innovators in Georgia.”

Brown also paid nearly $14,000 to a Portland, Ore., firm called Masterplans that specializes in developing business plans. The payments are listed as being for “Aug Invest” and “Sept. Invest.”

Jones, Brown’s finance director, said Masterplans developed Brown’s campaign platform, helped with messaging and audience targeting and designed the campaign’s logo.

He said the references to “invest” were probably typos.

“It should have been invoiced, probably,” Jones said. He said that was his way of indicating to his accounting department which invoice an expenditure goes with.

Masterplans did not return calls seeking comment.

The report also lists a $17.99 payment to Stamps.com in August for “Investor relations.”

Jones said the payment was likely for postage for sending t-shirts or other merchandise the campaign provides to contributors. “It's a way to label that people have gotten shirts and we've sent it to them,” he said. “This is how we stamped it and sent it out.”

Brown’s expenditures for fundraising events were also unconventional.

In July, Brown hosted a Health and Wellness Expo in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park, featuring a variety of yoga, fitness, nutrition and motivational trainers. The event was free for attendees but promotional material stated that “Proceeds will go to support Councilman Antonio Brown.”

Brown reported no contributions of more than $100 on the date of the event in his campaign finance disclosure. Expenses listed in the report for the day of the event included $444 for a U-Haul rental, $110 to rent a generator, unspecified labor costs of $350 and $650 to hire DJ Boogie Lov.

Jones said the campaign took in money from the event by providing tables for vendors at $100 each and “sales through Eventbrite,” an online ticketing service. Jones did not respond to a follow-up request to explain what was being sold through the service.

Jones also said some of the trainers livestreamed their exercise sessions. “A lot of them kind of got their circle to donate,” he said.

If those donations were not more than $100, the campaign would not have to report them individually. Jones said he did not know off the top of his head how much the campaign took in from the event.

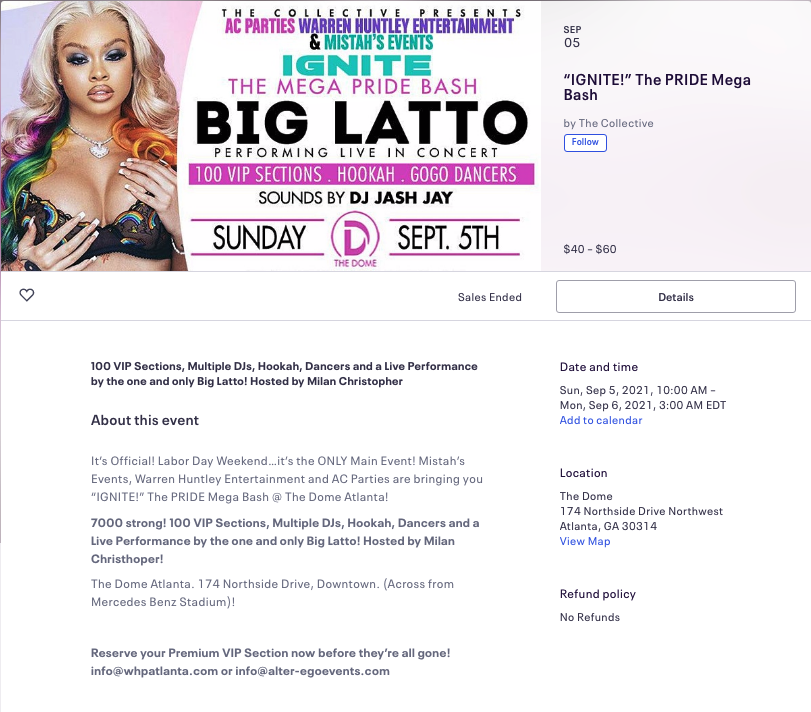

An EventBrite link for a Pride weekend party that Atlanta mayoral candidate Antonio Brown's campaign spent money to help put on does not mention the campaign at all.

The largest event expenses for Brown, who is openly LGBTQ, were for a series of Black Gay Pride events that took place over Labor Day weekend. The campaign paid $56,000 for use of a venue known as Dome Atlanta, a “pop-up” club in Vine City that has become notorious for hosting loud events that last well past the city’s 3 a.m. closing time, disturbing area residents.

The campaign also paid $75,000 to the Richard De La Font Agency of Oklahoma to provide entertainers for the events, according to Jones. The featured entertainer at the main event on Sunday Sept. 5 was the rapper Big Latto. Brown’s campaign also paid $1,000 to actor and influencer Milan Christopher to promote the events.

"This Sunday Atlanta pull up to The biggest party in the A this Laborday weekend- at the DOME - Sunday night," the influencer tweeted on Sept. 2.

Although Brown’s campaign said they paid for the venue and entertainment, much of the promotion for the “Ignite: The Mega Pride Bash” event makes no reference to Brown.

The Eventbrite page for Brown’s campaign committee, the Committee to Reimagine Atlanta Together, does not list the Dome event among past fundraisers.

A flyer on Brown’s Instagram said the event was paid for by the Committee to Reimagine Atlanta, and provides a link to book table reservations that appears to be a Cash App account for Brown. The flyer does not indicate ticket sales or table reservations would benefit his campaign.

Jones said the campaign took in money through the sale of tickets, which cost $40-$60, under the itemized reporting limit. He said he did not know how much the campaign raised through the events at the Dome but it was a “big moneymaker.”

“I definitely think it would be odd to try to promote a fundraising event and not identify it’s a fundraising event,” said Rick Thompson, a member of the Georgia Government Transparency & Campaign Finance Commission, which regulates election law in the state. “I don't know how fair it is for individuals buying those tickets to not know it's a fundraising event.”

“Could somebody take exception because they wanted to go to the event, but they could say, ‘I wouldn't have gone to the event if I knew it was for this person or that person,’” Thompson said.

Last spring, when frustrated neighbors complained about deafening late-night music blaring from the tent-like Dome, Brown, who represents the area, intervened.

After meeting with the owner of the facility, Brown announced a resolution.

“The solution is to redirect the sound from being projected towards the community and redirecting it,” Brown told reporters, according to the AJC.

Yet the disturbances continued.

Between midnight and 3:30 a.m. on Sept. 6, at the tail end of the Black Gay Pride events, the Atlanta Police Department fielded five calls for noise complaints at the Dome’s address, as well as a report of a fight and an injured person requiring an ambulance, according to police records.

Brown did not reply to a message seeking comment.

— Georgia News Lab intern reporter Liset Cruz contributed reporting for this story.