Section Branding

Header Content

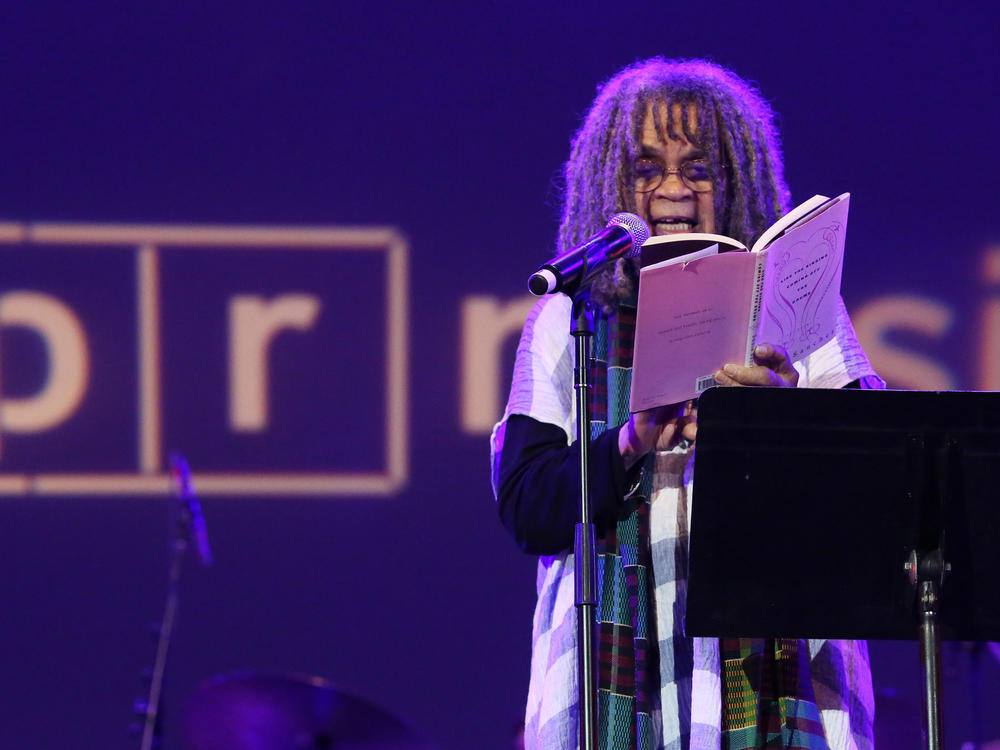

For poet Sonia Sanchez — at age 87 — there's more work to be done

Primary Content

Maya Angelou once called the poet Sonia Sanchez "a lion in literature's forest. When she writes she roars, and when she sleeps other creatures walk gingerly."

For over 60 years, Sanchez has helped redefine the landscape of American politics and literature. As a leading figure in the 1960s Black Arts movement and one of the first people to set up a Black Studies program at an American university, Sanchez's life and work have established her as one of the greats in American poetry.

Last month, she won the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize — a $250,000 lifetime achievement honor given to "a highly accomplished artist from any discipline who has pushed the boundaries of an art form, contributed to social change, and paved the way for the next generation."

Combining Black slang, traditional forms and jazz music on stage

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Sanchez wrote her very first poem around the age of five, and she's still going. This spring, she published her Collected Poems — a book that spans four decades of work.

Sanchez draws deeply on Black oral traditions, skilfully mixing blues bars with traditional Japanese forms like haiku and tanka. She's known to bring jazz musicians, drummers, and other musical guests on stage to aid and elevate her performances.

Poet Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, whose father was also part of the Black Arts Movement, was a teenager when she first saw Sanchez read.

"At the time, I don't believe I noted that she was a very petite woman," Jeffers says. "Because she had such a huge presence."

Indeed, Sanchez is never a bigger force than when she's up on stage actually reading her work out loud. In 2002, she was one of the first guests to perform on HBO's spoken word poetry series Def Poetry Jam. Show creator Danny Simmons, who is a friend of Sanchez's, says she's part of the reason the show even exists.

He remembers bringing Sanchez in to read for a director he'd hoped would work on the show, and her poem brought the man to tears. "I mean he literally sat there and cried," Simmons says. "And he said, 'I'm going to do it. I'm going to direct it.'"

Lifting Black voices through art — and then education

Simmons says that the spoken word and its power to create change is at the core of Sanchez's work. That's evident in her involvement with the Black Arts movement: Inspired by Malcolm X, Sanchez and her contemporaries — other legendary writers like Toni Morrison, Nikki Giovanni, and Amiri Baraka — worked vigorously to lift Black voices through art. And when they spoke, Sanchez says, "people would jump up, I mean literally jump up and stamp their feet."

She even took the movement into the world of education by pioneering one of the first Black Studies programs in the country. "I remember telling my dad, I'm going to go to a place called San Francisco to begin something called Black Studies," she says. "And he said, whoah, Sonia, you don't wanna do that."

Imani Perry, a Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, once persistently — and successfully — called Sanchez to come speak at her high-school graduation. She says that Black Studies is one of the few academic fields that had a direct connection to poor and working class people right from the start.

"[Sanchez talks] about her childhood in Birmingham and local celebrations of black culture as a kid," Perry says. "So even before she was involved in the formal institutionalization of black studies, she [brought with her] the work that teachers did in the deep South."

Influencing a generation of younger poets

Part of Sanchez's power comes from advocating for her people — and from blazing a trail for poets who came after her. Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, who now has five poetry collections and a novel, says she learned how to lean into her power through Sanchez.

"I remember how Miss Sonia would close her eyes sometimes when she would read," Jeffers says, thinking of one of her earliest readings in front of a big crowd. "And so I closed my eyes and I felt something enter me. And when I opened my eyes, I wasn't scared anymore."

Like Jeffers, poet Reginald Dwayne Betts was also guided by Sanchez's voice. He was incarcerated when he first read her work. Now a 2021 Macarthur fellow and the author of three books, he says the first poetry book he bought with his own money was Sanchez's 1987 collection Under a Soprano Sky.

"I've been in dark places where her poems brought me to light. And it's kind of cool to see the world catching up," Betts says. "But the truth is, Gish prize or no Gish prize — I once was shackled in handcuffs for 17 hours, and the most valuable thing that was in my property was Under a Soprano Sky."

This story was edited for radio by Petra Mayer, and adapted for the Web by Jeevika Verma and Petra Mayer.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.