Section Branding

Header Content

Prosecutor says the McMichaels chased Ahmaud Arbery for 5 minutes before killing him

Primary Content

Updated November 5, 2021 at 8:42 PM ET

Opening arguments in the trial over Ahmaud Arbery's killing began Friday morning, with Travis McMichael; his father, Gregory McMichael; and their neighbor William "Roddie" Bryan facing murder charges.

Prosecutors are urging jurors to convict the three white men of several felonies, saying they chased Arbery, a Black man, through a neighborhood in Glynn County, Ga., and shot him to death with a shotgun.

The defense says Travis McMichael shot Arbery three times in self-defense, as the McMichaels and Bryan attempted to conduct a citizen's arrest of Arbery under their suspicion that he might have stolen something from an under-construction house.

Arbery, 25, was killed on Feb. 23, 2020, after he was seen running in the Satilla Shores neighborhood, in what his family calls a modern-day lynching. The case has fueled intense protests over racial inequality in the U.S., with key details emerging in the weeks before George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis.

It took nearly three weeks to select a jury for the trial. The 12-person panel includes 11 white people and one Black person, even though Black potential jurors made up one-fourth of the final pool. The jury also has four alternates. The trial is expected to last around two weeks.

What are the charges?

A grand jury indicted Gregory and Travis McMichael and William Bryan on nine criminal counts in Georgia state court, including felony murder, aggravated assault and false imprisonment.

The June 2020 indictment accuses the men of using their pickup trucks to chase and assault Arbery before killing him with a 12-gauge shotgun.

Who are the defendants in the case?

Gregory McMichael, 65, worked in law enforcement for decades, including a long stint as an investigator for the district attorney's office in Brunswick. After spotting Arbery, McMichael later told police, he grabbed his .357 Magnum pistol and told his son, "Travis the guy is running down the street lets go."

Travis McMichael, 35, shot and killed Arbery with a 12-gauge shotgun after chasing him in his Ford F-150 pickup. He is a former member of the Coast Guard.

William "Roddie" Bryan, 52, is the neighbor who jumped into his Chevrolet Silverado pickup to help chase Arbery. He used his cellphone to record video of the final moments of the confrontation.

Ten weeks passed between Arbery's death and the first arrests in the case, after a video of the killing became public.

The McMichaels and Bryan assumed the worst about Arbery, the prosecutor says

Lead prosecutor Linda Dunikoski began her opening statement by telling the jury that all three of the defendants made decisions in their driveways, based on "assumptions — not on facts, not on evidence." Those decisions resulted in Arbery losing his life, she added.

Dunikoski says Arbery lived with his mother. "He was also a brother, he was an uncle — and he was also an avid runner," she added. She said the jury will see photos of Arbery's shoes, with the treads nearly worn off.

After showing aerial photos of Satilla Shores, Dunikoski focused on 220 Satilla Drive — "an open, unsecured construction site" for a house owned by Larry English — who, she told the jury, lived two hours away and barely knew the McMichaels.

Dunikoski said nothing was stolen from the site in 2019 or 2020. But in late 2019, she added, English realized some items were missing from inside his boat nearby. He set up motion-activated surveillance cameras, and while Arbery was seen wandering around inside the house several times, he never took anything, Dunikoski said. Instead, it was a white couple who were seen carrying a bag at the property that aroused English's suspicions, she said.

But on Feb. 23, 2020, "Greg McMichael assumed the worst" after he saw Arbery "hauling a**" down the street away from English's house, Dunikoski said. He quickly ran inside to get his pistol and alert his son, who grabbed his shotgun and jumped into his truck. Greg McMichael rode in the cab, straddling his grandson's car seat, she added.

Travis McMichael acted out of 'duty and responsibility,' his attorney says

"This case is about duty and responsibility," said defense attorney Robert Rubin, who represents Travis McMichael. "It's about Travis McMichael's duty and responsibility to himself, to his family, and to his neighborhood."

Rubin says that from 2007 to 2016, Travis McMichael was "a boarding officer in the Coast Guard, which means he was authorized to make arrests. He was authorized to do investigations. He was authorized to do searches. He was authorized to use his weapon when appropriate."

Travis McMichael was trained in law enforcement concepts such as probable cause and the use of force, Rubin said. He added that the training went beyond the classroom to focus on actual scenarios.

"It is repetitive training, so that if you're ever in a real-life situation where you need to make use-of-force decisions, you're relying ... on muscle memory because those split seconds are often the difference between life and death," Rubin said.

Rubin portrayed Satilla Shores as an idyllic place, a neighborhood perfect for kids. At the time Arbery died, Travis McMichael and his young son were living there with his mom and his father.

"This is the family and community that made him willing to put himself at risk to help the police detain Ahmaud Arbery," Rubin said.

The video of the pursuit of Arbery doesn't tell the whole story, Rubin said, because in 2019, the neighborhood started seeing a rise in property crime.

"As a result of this uptick in crime, of people being on edge, people were alert to suspicious behavior" — including setting up surveillance cameras, Rubin said. He went on to describe Larry English's attempts to stop people from going into his under-construction house. Cameras spotted Arbery at the property four times over the course of several months, he said.

The McMichaels and Bryan chased Arbery but did not call 911 right away, the prosecutor says

When the McMichaels started to chase Arbery, neither man called 911 immediately. It was a different neighbor who lived nearby who first did that, after seeing Arbery leave the English house, Dunikoski said. As the McMichaels chased and shouted at Arbery from their truck, Bryan saw them and joined the chase.

"At this point in time, Mr. Arbery is under attack" by all three men, as they repeatedly drove their trucks at him, Dunikoski said. They got so close, she added, that Arbery's handprint was found on Bryan's truck, along with fibers from his T-shirt.

"Mr. Arbery ran away from them for five minutes," Dunikoski said.

She said Greg McMichael told police that he had yelled at Arbery, "Stop, or I'll blow your f***ing head off!"

She then played the cellphone video Bryan recorded of the incident, culminating in Arbery being shot at close range after a struggle with Travis McMichael. The footage showed that Travis McMichael blocked the street with his truck and got out with his shotgun, then moved around his truck to raise his weapon and confront Arbery, Dunikoski said.

Greg McMichael called 911 moments before the fatal shot was fired. Playing audio of that call in court, Dunikoski said the emergency McMichael cited to the dispatcher was that a Black man was running down the street — not that he had committed a crime.

None of the defendants told Arbery that they wanted to place him under citizen's arrest, Dunikoski said, adding that they had "no immediate knowledge of any crime" Arbery might have committed. She said Greg McMichael also assumed — wrongly, it turned out — that Arbery was probably armed. The prosecutor said Arbery wasn't carrying anything, not even his keys or a cellphone.

Describing a circumstance she called "truly, truly tragic," Dunikoski said that by the time the shots rang out, the officer who was dispatched by the initial 911 call had already arrived in the neighborhood. He was driving slowly through the area, looking for suspicious activity, when he heard the gunshots, she said.

Travis McMichael didn't want to shoot Arbery. He only wanted to detain him for the police, defense argues

On the day of the violent shooting, Rubin explained there were four separate encounters between his client, his client's father and Arbery.

But the day had begun peacefully. Travis McMichael was on the couch, trying to get his 3-year -old son to take a nap. That was interrupted by his father, running into the house, saying: "Travis, the guy is running down the street."

Apparently, Arbery had been spotted by another neighbor who had called 911 after he'd seen the man exiting the English house again.

Both McMichaels grabbed their guns — the younger McMicheals, a shotgun, the older one, a pistol — and jumped into their Ford 150, to chase after Arbery.

"They are there to detain Ahmaud Arbery for the police. This is what the law allows," Rubin told the jury.

In each instance in which they confronted Arbery, Rubin depicted the McMichaels as calm, polite and even a little gentle. Throughout the lawyer's hour-long account, there was no mention of threats, cursing or even harsh words, as the prosecution suggested.

Meanwhile, Rubin described Arbery as a suspicious outsider who was caught on camera "plundering" through the construction site, although he never stole anything from the empty house. And after showing surveillance images captured at the English property months before the killing, Rubin said: "The question remains, was he out for a jog at 10 o'clock at night on Dec. 17th or was he doing something else? We'll never know but it sure does look suspicious."

When McMichael and his father caught up to Arbery on the side of the road on Feb. 23, Rubin said, his client leaned out of the car and calmly asked, "What were you doing back there?"

Arbery allegedly did not respond. Instead he turned to run in the opposite direction. When Travis McMichael backed up to continue to follow Arbery, and ask again, Rubin said, "He didn't say, 'Hey good morning.' He just turns around and bolts."

Rubin suggested to jurors that Arbery's silence was odd given that "at this point, there is no gun." His client's shotgun was stuck between the seats, while his father's gun was at his hip in its holster, he explained. "Arbery is not aware of any gun," Rubin said.

Arbery only saw the gun after the McMichaels had gotten out of the truck and tried to block Arbery from running past them. But at that point, his client was only brandishing the weapon in an attempt to deescalate the situation and get compliance, as he'd been trained to do, Rubin told the jury.

But the attempted warning did not stop Arbery, he said; Arbery kept running toward McMichael, ending up on the passenger side of the truck where McMichael couldn't see his hands. "Remember, he still thinks this guy could be armed," Rubin reminded the jury. Within seconds, Arbery "is on Travis such that Travis has no choice but to fire his weapon in self-defense."

And after that first shot to the chest, McMichael fired three more shots into Arbery, who continued to swing wildly at him and try to pull the shotgun away, Rubin said.

"And you've seen that it's a horrible, horrible video and it's tragic. It's tragic that Ahmaud Arbery lost his life. But at that point, Travis McMichael is acting in self-defense. He did not want to encounter Ahmaud Arbery physically. He was only trying to stop him for the police."

Greg McMichael's lawyer says his client was in abject fear for his son's life

Greg McMichael's attorney, Frank Hogue, echoed much of the same story relayed by his son's attorney, Bob Rubin.

Hogue talked about the string of alleged thefts that had been shared in local Facebook groups and said the elder McMichael, who is a retired investigator the Brunswick district attorney's office and a former Glynn County police officer, "was right" when he decided that the Black man perfectly matched the description of the photos passed around by local police; Arbery was 5' 10", slender and muscular, had short hair that was also in twists, and he was "hauling a**" running past the McMichaels' home in broad daylight.

It was clear to Greg McMichael that this was the man who had burglarized the house, Hogue said, and that is why he sprung into action.

His objective was not to harm Arbery, Hogue said. He wanted to detain him for police questioning.

"This case turns on intent, belief, knowledge, reasons for those beliefs," Hogue explained.

He asked: "Were there good reasons to believe that this young man, Ahmaud Arbery, had been in this house where things had been taken and that he may have been the person who took them? Were there good reasons that as he ran passed Greg McMichael that day that he was fleeing from someone or something who had seen him in that house?"

By the time McMichael and his son had created the makeshift barricade to stop Arbery, he was on a cell phone call with 911 telling police where they could find the man.

When he saw Arbery running toward his son, Hogue said Greg McMichael yelled, "Stop right there. Damn it! Stop!"

"He's now in abject fear that he is about to witness his only son possibly be shot and killed in front of his very eyes," he told the jury.

Hogue argued the shooting was justified as self-defense.

The attorney made no mention of the call McMichael made to former Brunswick Judicial Circuit District Attorney Jackie Johnson, whom he called for advice moments after the deadly shooting.

An investigation, which led to an indictment of Johnson for violating her oath of office and hindering a law enforcement officer, showed Greg McMichael called Johnson's cellphone and left her a voice message.

"Jackie, this is Greg," he said, in the message. "Could you call me as soon as you possibly can? My son and I have been involved in a shooting and I need some advice right away."

What will the trial include — and not include?

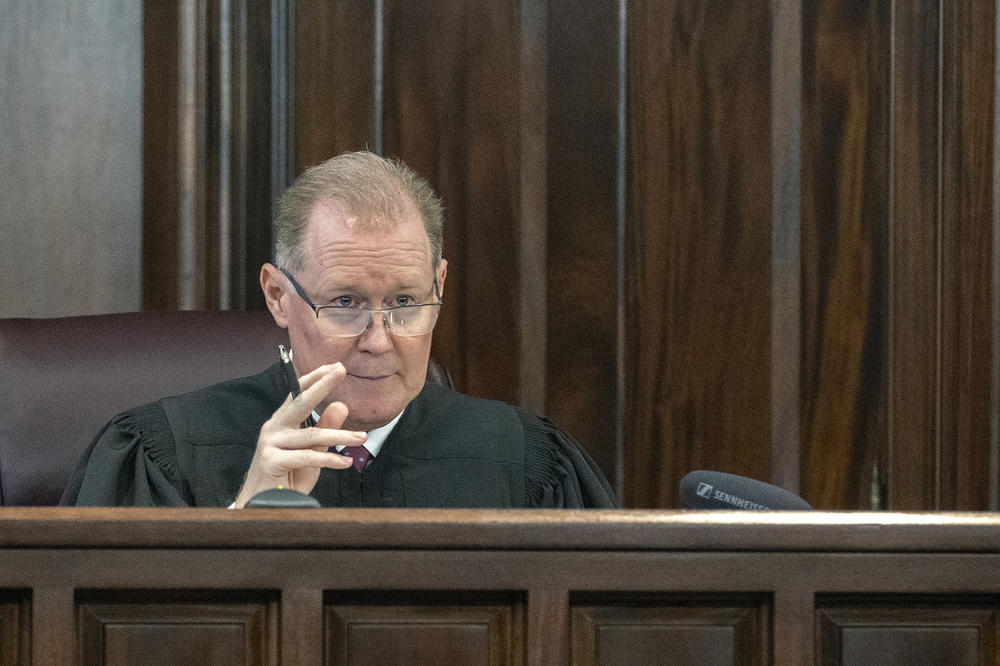

Prosecutors won two victories the day before opening arguments began, with Judge Timothy Walmsley largely siding with their views on evidence that will be allowed in court. Here's a quick rundown:

Toxicology reports on Arbery: Lead prosecutor Linda Dunikoski says they're irrelevant, as Arbery had zero blood alcohol content. She said a follow-up screening for prescription drugs found a "minute" amount of THC, the psychoactive agent in cannabis.

Defense attorney Jason Sheffield said Arbery was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder in 2018, and he wants an expert to testify whether that, in combination with THC, could make someone aggressive or combative. The judge has already ruled Arbery's mental health history won't be part of the trial; he says the traces of THC won't either.

Officer bodycam video: The McMichaels' attorneys sought to block what they called "inflammatory" portions of video from an officer's body camera. The footage, from the second officer who arrived at the scene, includes a close-up view of Arbery's body as he lay on the ground after being shot.

Prosecutors responded by saying that the images are "real" — that they accurately show what happened. The judge ruled the full video will be included in the trial. He added that anyone who needs to leave the courtroom during the moments when it's shown should feel free to do so.

Arbery's probation status: The judge also granted the state's motion not to include information about Arbery's probation status. The defense had said it wanted to introduce that as a possible reason why Arbery would want to flee.

License plate: In another ruling, the judge denied the defense's attempt to suppress images of the vanity license plate on the front of Travis McMichael's truck, which depicts the former Georgia state flag — a banner that was replaced in the early 2000s because it evoked Confederate imagery.

Who are the judge, prosecutors and defense?

Superior Court Judge Timothy Walmsley is presiding over the trial at the Glynn County Courthouse. The Eastern Judicial Circuit judge was given the case after all five judges in the Brunswick Judicial Circuit recused themselves. Walmsley was appointed to the bench in February 2012.

Lead prosecutor Linda Dunikoski is the senior assistant district attorney in Cobb County, outside of Atlanta. She was put in charge of the case in April, after two local prosecutors recused themselves.

Defense attorney Kevin Gough of Brunswick has represented Bryan since his arrest. Attorney Jessica Burton of Atlanta is also on Bryan's defense team.

Defense attorneys Robert Rubin and Jason Sheffield represent Travis McMichael. They're from the same Atlanta-area law firm.

Defense attorneys Laura and Franklin Hogue, who are married, represent Greg McMichael. They're based in Macon, Ga., where they've handled numerous death-penalty cases in the past.

Along with the state charges, a federal grand jury indicted the McMichaels and Bryan on hate crime charges in April.

The federal charges also include the attempted kidnapping of Arbery, and the McMichaels are charged with using firearms during a violent crime. A February trial date has been slated for those charges.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.