Section Branding

Header Content

Rebels are closing in on Ethiopia's capital. Its collapse could bring regional chaos

Primary Content

A year after civil war erupted between the Ethiopian government and its Eritrean and ethnic militia allies on one side, and soldiers hailing from the northern region of Tigray on the other, a once-unlikely scenario looks like a real possibility: the rebels could topple the government.

This past week, Ethiopia declared a state of emergency amid fears that soldiers from the armed wing of the Tigray People's Liberation Front, or TPLF, would march through the streets of the capital, Addis Ababa. The federal armed forces have appealed to retired soldiers and veterans to rejoin the military. And they have asked residents of Addis Ababa to join the war effort with whatever weapons they have.

The TPLF, supported by the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) — a rebel group from Ethiopia's Oromia region — are a bit more than 200 miles from the capital, but it could still take days or weeks of fighting across mountainous and hostile terrain for them to close the distance, the latest reports from inside the country suggest.

Saturday the U.S. State Department ordered "non-emergency U.S. government employees and their family members" to leave Ethiopia. The White House has declared the situation in Ethiopia "an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States," and the U.S. special envoy for the Horn of Africa, Jeffrey Feltman, arrived in Addis Ababa on Thursday to push for cease-fire talks.

Neighboring Kenya issued a plea to end what it calls a "nationwide social convulsion." China and Russia, who had been reluctant to weigh in on the conflict, joined a U.N. Security Council statement calling for an "end to hostilities."

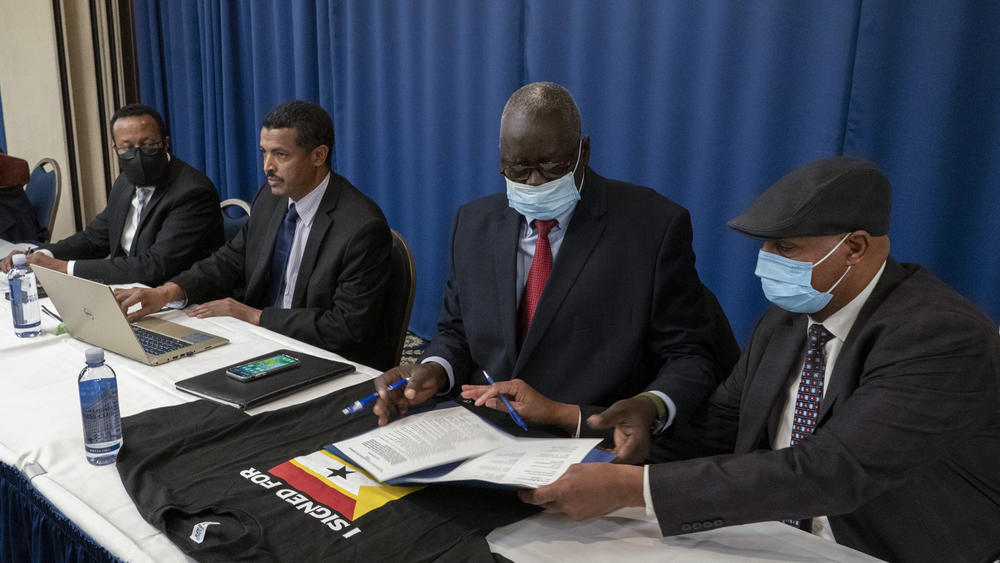

On Friday, the TPLF and OLA signed an alliance with seven other rebel groups. "Definitely we will have a change in Ethiopia before Ethiopia implodes," Berhane Gebrechristos, a former foreign minister and Tigray official, told reporters at a signing ceremony in Washington, D.C.

For Ethiopia's prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, it has been a sharp turn of events. He's gone from freshly minted Nobel Peace Prize laureate to international outcast in less than two years. Abiy now faces grim prospects: continue a war that could easily spill into the densely populated capital, a defeat at the hands of a renegade army or a negotiated settlement that would severely weaken his position.

Before the prime minister came to power in 2018, the TPLF ruled Ethiopia for more than a quarter century and waged two intensely bloody wars: a 15-year conflict that toppled a communist military dictatorship and saw the country's Eritrean region win independence, and years later a much shorter but brutal border conflict with the newly formed country.

One of Abiy's first moves was to extend an olive branch to his Eritrean counterpart, President Isaias Afwerki, an overture that led to the Ethiopian leader receiving the Peace Prize in 2019.

But there remains "a lot of bad blood" between Eritrea and the Tigrayans, says Michelle Gavin, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. She says there's "a lot of historical grievance coming from the Eritrean elite and [aimed] very specifically at the TPLF from that era," adding that the Eritreans still nurse a "sense of betrayal" over the years of violence.

The humanitarian situation is growing worse by the day

A report released Wednesday by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission blamed all sides in the year-long conflict for atrocities including extrajudicial executions, torture, rape and attacks on refugees.

While the U.N. did not come to a conclusion on whether genocide was committed, an internal U.S. report concluded that last November, forces allied with Ethiopia's government "deliberately and efficiently" rendered Western Tigray "ethnically homogeneous through the organized use of force and intimidation."

While all factions have committed violence against civilians, Cameron Hudson, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council's Africa Center says the most egregious human rights abuses in Tigray have been carried out by Eritrean soldiers. "They have tried to eliminate the Tigrayans," he says, "and there's no telling what the Tigrayans might be interested in doing if they were able to seize the upper hand against the Ethiopian government."

Amnesty International says Eritrean soldiers slaughtered hundreds of unarmed civilians in the northern Tigrayan city of Axum, "opening fire in the streets and conducting house-to-house raids in a massacre that may amount to a crime against humanity."

NPR has independently verified reports of sexual violence in Tigray, speaking with witnesses and victims, including one woman in the rebel capital of Mekele who was held captive for about a month by government forces. The woman told NPR that she was chained up for nine days and gang-raped by Eritrean soldiers.

Ethiopia's government declared a cease-fire this summer, pulling its troops out of Tigray. But fighting continued and the government has employed strategic choke points to maintain a de facto blockade on the wayward region that "has been nothing short of devastating for civilians," according to Refugees International.

That has made it nearly impossible for aid trucks to enter and relief flights to land, Alex de Waal, the executive director of the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University's Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, tells NPR. "That is a piece of what makes it so very difficult to get humanitarian material into Tigray."

The U.N. called for access to the region in July, warning that some 400,000 people there had "crossed the threshold into famine," with 1.8 million more on the brink. The same month, the U.N. refugee agency said that a full-scale humanitarian crisis had been unfolding in Tigray since the start of the conflict, with more than 46,000 people fleeing to neighboring Sudan and an additional 1.7 million internally displaced.

If Addis Ababa falls to the rebels, Ethiopia could collapse, triggering regional chaos

There's "a tremendous amount of anger" in many parts of Ethiopia over the legacy of the TPLF's long and repressive rule that is "unquestionably going to lead to resistance," the CFR's Gavin says.

Ethiopia's regional states are largely divided along ethnic lines and have their own militia groups, Hudson, of the Atlantic Council, says.

"They have feuds, they have grudges against their neighbors and against the central authorities," he says. "So, I think the question is what becomes unleashed by the fall of the government?"

Amnesty International on Friday offered a sobering assessment, noting in a statement sent to NPR that there had been "an alarming rise in social media posts advocating ethnic violence" in the country in recent says.

More broadly, an internal collapse of Ethiopia could have repercussions for the whole of east and northeast Africa. Eritrea's leader views the rise of the Tigrayans as "an existential threat," Hudson says. Kenya is worried about an influx of refugees and a humanitarian crisis on its doorstep, a problem with which Sudan is already all too familiar.

"You're talking about millions of refugees flooding a very unstable region. You're talking about a humanitarian catastrophe," Hudson says. "The disruption that causes, not just to Ethiopia and neighboring states, but well beyond, is cataclysmic."

It could make the U.S. fight against terrorism much more difficult

For Washington, the biggest regional concern is Somalia and the potential for that nation to be used as a platform for international terrorism.

Ethiopia has long helped keep a lid on the Islamist al-Shabab militia, and offered crucial backing for the fragile government in Somalia, which seems to be ever on the verge of anarchy.

Ethiopian forces "are a powerful actor in Somalia," writes Vanda Felbab-Brown, senior fellow in foreign policy at the Brookings Institution. "Their military heft significantly surpasses that of the Somali National Army (SNA) or Somali National Police (SPN)," which she says have "little independent capacity even for defensive operations against al-Shabab."

A failed state in Ethiopia would likely make things much worse there, the CFR's Gavin says. "Instability in Ethiopia is absolutely a boon to terrorist organizations in East Africa writ large."

The Atlantic Council's Hudson agrees that such environments are a breeding ground for extremism.

"I think you create a scenario where this part of the world is exporting instability well beyond it," he says. "It becomes a magnet for malign actors seeking a home base."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.