Section Branding

Header Content

As he leaves the Marines, a Navy Cross recipient finds purpose through tragedy

Primary Content

Nick Jones says he was born to be a fighter. He is cool under chaos and thinks quickly on his feet, both of which served him well in the Marine Corps. And like others who choose to join the armed forces, Nick wanted to be a part of something bigger than himself.

But individual experiences in the military vary. And Nick's career, half of which he spent as a Marine Raider in MARSOC, the Marine Corps' special operations group, is mired in despair.

He suffered one tragedy after another over the course of his 11-year-career, losing friends in both combat overseas and disasters at home. On one occasion, he was charged with informing his best friend's widow of her husband's untimely death, which he said may have been the hardest thing he has ever had to do.

His journey through the Marine Corps culminated in March 2020 on a mountainside in Iraq. It was there that he narrowly cheated death while desperately trying to save two of his wounded teammates, for which he would later be awarded the Navy Cross — second only to the Medal of Honor.

But he didn't walk away unscathed. A single bullet to the leg would cost him his Marine Corps career and force him into medical retirement at 29 years old.

Like everyone else who inevitably leaves the military, Nick had to figure out what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. He spent over a year and a half lost in the pain. Having lost a number of his friends, the use of his leg and his livelihood all at once, Nick was afraid of the future and regularly caught himself thinking, "I have no idea what to do."

A battle marked the beginning of the end for Nick's military career

The operation was in its early stages when things started to go horribly wrong. It was March 8, 2020, and Nick and his fellow Marines joined Iraqi security forces on a mission to clear out a cave system harboring Islamic State fighters in the Makhmur mountains in northern Iraq, about 40 miles outside Irbil.

A massive firefight erupted on the mountainside. Along with one French special forces soldier, two of Nick's comrades were gravely wounded. Time and time again, Nick fought his way up the mountain, trying to save his friends who lay dying at the mouth of a cave defended by enemy combatants. But each time, he was met with a barrage of fire that drove him back down. Nick was shot through the leg during his final uphill assault and had to be airlifted off the mountain.

Despite his best efforts, he could not save his friends.

Gunnery Sgt. Diego Pongo and Capt. Moises "Moe" Navas were both 34 years old. Their bodies were recovered the following day by members of Delta Force, an Army special operations force. Nick and his teammates traveled three or four hours to an airfield in Irbil to see their fallen teammates off. Holding back tears, Nick leaned on his crutches and watched as his teammates loaded the coffins onto the plane destined for home. He followed them onto the plane and immediately broke down.

"I was angry and sad. I couldn't stop crying, honestly. At that point, a part of me [felt] like I failed," he said. "Seeing them being wheeled onto the bird, you know, it wasn't anywhere close to closure for me because I wasn't the one to get them out of there. I wanted to be, but at least I knew that they were back and they were going home."

He became lost in the pain

Over a year, Nick underwent six surgeries, which were initially geared toward allowing him to deploy again. But the bullet, which he described as a pinprick, had severely damaged the perineal nerve in his right leg. And as a result, he suffered from chronic pain along with tingling and numbness.

Running out of treatment options, Nick's doctors recommended a spinal cord stimulator to help mediate the pain. Four electrodes would be embedded in his back along the spine, placed under the skin in his lower back along the waist.

Worried about his future as an elite military operator, Nick asked the doctors if the device would hinder his ability to do his job. When they told him it would likely limit his movements and could very well be a permanent addition to his body, he knew his time in the Marine Corps was coming to a close.

"Being lost in the pain and the suffering from losing my teammates was such a freaking weird time for me," Nick said. "Then learning about retiring, it's like, I [had] no idea what to do."

Being forced into a medical retirement from the Marines was something Nick had never contemplated before. He thought he would either die while fighting overseas — a very real possibility — or continue to excel in his career until he put in 20 or so years and then retired with a military pension. With the future he had envisioned for himself no longer an option, he began to descend into depression.

Unable to do much of anything on his own while he was recovering from his surgeries, Nick had to rely on his 25-year-old fiancée at the time, Hanah, to care for him. She helped bathe him and dressed his wounds. Hanah even carried him from the car to the front door on at least one occasion.

Nick tried to help out around the house, but the pain often proved to be too much. So Hanah cooked, cleaned the house and somehow found time to walk their three dogs, all while working a full-time job as a fitness instructor.

It pained her to see Nick laid up at home. They used to enjoy hiking together, along with snowboarding and other outdoor activities, many of which were now beyond Nick's capabilities. As strong as Nick was, Hanah worried about his mental health when the flashbacks started.

"It's heartbreaking because these are obviously real, raw emotions," she said. "He has them in his nightmares that he still has to this day. He still whimpers in his sleep, shouts in his sleep. He wakes me up by screaming or punching the bed in his sleep."

The reason Nick sometimes punches and screams his way through the night is deep down, something inside him is broken. A part of him is hurting because of the things he did and didn't do — perhaps couldn't do — while in the Marine Corps.

For the longest time, Nick felt responsible for the deaths of his two teammates. And now, with his exodus from the Marines all but certain, he would be unable to protect the rest of his team.

For many veterans, reckoning with the past means "moral injury"

Some days were better than others in the months that followed his deployment to Iraq. Sometimes he could talk about what he went through; other times he felt it best to keep his thoughts to himself. But in June 2020, when the anguish became practically unbearable, Nick sought help.

The mental health specialists who evaluated Nick at Camp Pendleton diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder and a traumatic brain Injury, both of which are a direct result of his combat experiences. To address his trauma, Nick has met with a mental health specialist once a week for the last 16 months.

But for Nick, one of the events that hurt him the most took place far from the battlefield. Nick's best friend in the Marine Corps, 27-year-old Talon Leach, was killed, along with 14 other Marines and one Navy corpsman, in a KC-130 plane crash while traveling from North Carolina to Arizona in July 2017. Nick was charged with breaking the news to Leach's wife turned widow.

"That wasn't anything related to combat and was one of the most painful things I've ever done," Nick said. "And trying to cope with that afterwards, why that? Does that happen for a reason?"

The Rev. Rita Brock, the daughter of a medic who served in the Korean and Vietnam wars, has spent over 50 years examining the crossroads of theology, religion and psychology. Before becoming the senior vice president and director of the Shay Moral Injury Center at Volunteers of America, she spent five years as the director at the Brite Divinity School's Soul Repair Center.

Brock has never met Nick, but she categorized his feelings of helplessness and guilt, along with an array of other emotions that come with trauma, as symptoms of moral injury. When someone carries out or witnesses something that goes against their moral code, Brock explained, it can cause emotional, behavioral and psychological damage.

On the surface, moral injury may seem similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, a mental health issue weighing heavily on service members and veterans, but though they are similar, they're not the same.

According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, veterans can develop PTSD by witnessing or living through a dangerous event. Consequently, symptoms are driven by a fear-based reaction.

Between 11% and 20% of post-9/11 veterans have PTSD. For many of them, it stems from their experiences overseas and can lead to symptoms such as hypervigilance, being uncomfortable in crowds or jumping when a door slams.

Moral injury, however, often stems from an event where something the individual did or failed to do violates part of their moral code. The VA says common reactions are feelings of guilt, shame, anger and even disgust with oneself.

Combat requires warriors to be both sinners and saints, capable of transitioning from hero to villain in a matter of seconds. Brock described moral injury as "heartbreak" — the toll that accompanies killing and seeing others be killed.

"Moral injury is not a disorder. It is what happens to ordinary, good people in extraordinarily devastating life experiences. And anyone is at risk for moral injury if they're a moral person, because we don't really have the kind of control over our lives we think we do," she said. "It's just what it means to be a human being who cares about others and lives in a world that has a lot of chaos in it."

A total of 6,923 members of the U.S. armed forces have been killed in action overseas since the United States kicked off its Global War on Terrorism campaign following the 9/11 attacks. Additionally, according to the Defense Department, more than 50,000 have been wounded. And like Nick, many of these men and women likely struggle to find the words to describe their experiences, let alone how those experiences have impacted them.

Service members don't have to see combat to suffer from moral injury. Brock said she treated a former Air Force pilot who never dropped a single bomb. The pilot, who served during the Cuban missile crisis, suffered because he realized he was willing to drop bombs and start a war with the Soviet Union.

These internal conflicts tend to get worse after an individual departs the military, because their support system is gone. Approximately 200,000 people leave the military every year, according to the Labor Department. Many of them go from being surrounded by people who love and understand them to a world of unfamiliar strangers they don't feel comfortable opening up to, Brock explained.

They do, however, need to open up. Many people struggling with moral injury tend to retract and pull away from friends and family. They can become cynical and irritable, which often comes hand in hand with alcohol and substance abuse.

"Trying to do it alone is really, really hard. And I think some people are deeply introverted and can manage it somehow, but most people need the support of people who love them ... finding that somewhere and in a relationship, in a community, in a small group of friends," Brock said. "Having a group of others that you trust not to judge you, but will listen deeply and validate how you feel — that's all it takes to get you on the processing journey."

A sudden realization helped him find another purpose

For Hanah and Nick, 2020 was both the best and the worst year of their lives. It started off awful when Nick was wounded overseas, which was made worse by the series of unsuccessful surgeries and the decline of his mental health.

But in September 2020, Hanah and Nick were joined by over 100 friends and family members in rural North Carolina for their wedding. Still in recovery, Nick walked with a cane at the time. He was also on antidepressants and painkillers, which he opted not to take on his wedding day so he could be clear minded and emotionally present. He wanted to remember everything.

And Nick was starting to get better. He wasn't back to hiking just yet, but he scooted alongside Hanah when she took the dogs out for their walks. He was still battling depression, but he started seeing a therapist and began treatment for his PTSD.

In October 2020, the Marine Corps gave Staff Sgt. Nick Jones the option to be medically retired. He could have taken a desk job somewhere, but that's not who Nick was and that's not what he wanted to do. The realization was painful, but he had come to accept the fact that his time as a warfighter was over.

Months passed as Nick pondered what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. With his departure from the Marine Corps imminent, he thought long and hard about where he had been, what he had done and what was important to him. Nick recognized that he had joined the Marines because he felt a calling to help others, and he didn't want to give that up just because he was leaving the military.

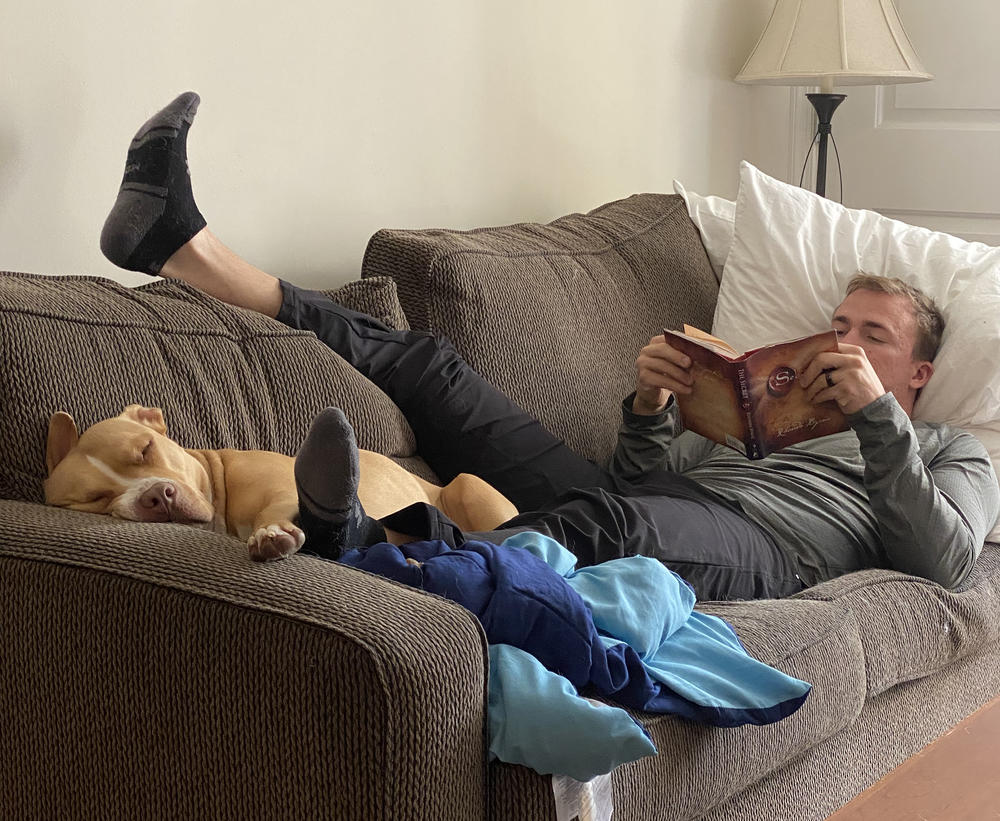

And one day, as he lay on the couch deep in thought, Nick finally realized what he wanted to do.

Nick is hard-wired to help others, which served him well in the Marine Corps. He loved mentoring new members of the team. They were a tightknit group, a family, charged with taking care of each other. And though he was leaving the Marine Corps, he wanted to continue serving members of the special operations community.

"I thought to myself, 'You know, there's a way for me to share my story and share what I've been through and the treatments that I've done with other people and maybe help people,' " Nick said. "I can make a foundation, and we can raise money and help people this way. I have no business background — I've never started anything like this — but I know the Marine Corps and the way that they raise us to never quit. ... I knew that if I started, I'm not going to fail at it."

Nick was excited. He started doing research into how to start a nonprofit and how to go about the fundraising process. His days of self-pity and loathing would soon be in the past as he took his first steps toward transitioning from the Marine Corps to life as a civilian.

When he ran the idea by Hanah, she was ecstatic. She was excited that he was excited, and it warmed her heart to see Nick's spirit return.

"This brought back the light in his eyes," she said. "We hadn't had that time for like a year because of everything. And I just took a deep breath and I was like, 'I will support you. You literally can do this full time and I will pay the bills. I don't even care because it gives you purpose and makes you happy. Then that makes me happy and then that means we'll be a happy family.' "

Nick submitted his paperwork for Talons Reach Foundation in January 2021, and by June it was approved as a nonprofit. The name is a double-entendre. Talons Reach is both a tribute to his fallen friend, Talon Leach, and a metaphor for the special operations community picking each other up. On deployments, the code called out on the radio when a teammate was wounded or killed was "Eagle down."

During his darkest days, Nick said, he had felt alone with nobody there to guide him. Yes, he attended therapy and, yes, his wife was always by his side, but he wished he had something else — something more structured to help him work through his mental health issues. He found solace in alternative treatments, including yoga, meditation and mindfulness practices, time spent outdoors — even painting. He wants to be there for other special forces members when they need a hand up.

He began to believe everything happens for a reason

Though the foundation isn't named after Leach per se, a series of peculiar events lined up in such a way that Nick couldn't write them off as coincidence. On Aug. 26, 2021, Nick was awarded the Navy Cross for his acts of gallantry on the day he was shot. It went widely unnoticed, however, because a suicide bomber detonated outside Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, Afghanistan, killing 13 U.S. service members and over 100 Afghans on the day of the award ceremony. It also happened to be Leach's birthday.

Not long after the bombing in Kabul, Nick drove from North Carolina to the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center just outside Washington, D.C., to visit those wounded in the blast. He spoke with the Marines, many of whom were suffering just as he had, lost in the world of what-if.

One Marine told Nick how he had been at the front lines outside the airport, surrounded by thousands of desperate people trying to flee the country. He was pushed to the ground and another Marine took his place, the Marine told him. When the suicide bomber detonated, it killed the Marine who had taken his spot on the line.

"He's blaming himself for it. And it's so hard to sit there and tell them not to do that, because I did the same freaking thing," Nick said. "I blamed myself, I blamed other people, but when trauma happens, it's so hard to control your thoughts. It's so hard to control the outcome because that's all you want to do — you want to change the outcome, but it's not real. You can't do it."

In October 2020, Nick and Hanah sold their house in North Carolina and bought their dream home 2,000 miles away in Montana. It sits on just over 2 acres just outside Bozeman and the peaks of the Bridger Mountains. In August 2021, they finally moved in. Nick has started hiking again, just a few miles at a time, but he's nonetheless excited to be with Hanah and the dogs.

There are still mental health mountains to conquer, and like with the mountain back in Iraq, he is taking it one step at a time, head up and eyes front until the mission is complete.

The Marine Corps gave Nick the opportunity to choose the date of his discharge. After some thought, he settled on Nov. 10, the Marine Corps' 246th birthday. And though he was able to leave the Marines three days earlier, it marks his last official day in the Marine Corps.

But it's not his last day as a Marine. That lasts forever.

Unlike some holidays, Veterans Day always falls on Nov. 11. This year, it carries a new level of significance for Nick. For the first time, he will experience it not as a member of the military or as a civilian, but as a veteran of the armed services.

He will hit the ground running as he prepares for the first group of six to eight Talons Reach participants, who will arrive in Montana next March, and there is lots of work to be done between now and then. He's still working to secure funds and volunteers, both of which have been in short supply because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But he couldn't be more excited.

As for Hanah, she still has some concerns about Nick's health, both physical and mental, but after making it through the last year and a half, she believes they can tackle anything, together.

"I really think down the road he's going to be happier off. And he'll always miss it, of course, and that goes without saying, but I think his mindset will shift," she said. "He doesn't see this now, but I do."

In his house, Nick has a vision board, a collage of pictures and words that help guide him toward his goals; on it is a picture of a beautiful log cabin surrounded by the Montana wilderness. And above the front door hangs a sign for Talons Reach Foundation. Below the picture he has written, "If not me, then who? If not now, then when?"

When he looks at it, as he often does, his confidence is restored. This is what he was destined to do.

Until very recently, the idea that everything happens for a reason had never sat well with Nick. He felt that was an excuse often used to justify the outcome when things didn't go according to plan. But now, having had time to reflect on his life, he's starting to believe otherwise.

"There's so many things falling into place with Talons Reach Foundation and with my move and the people that I'm getting connected to — it's like, maybe things really do happen for a reason," Nick said. "I don't get to serve necessarily side by side in the combat zone anymore, but I at least get to serve side by side with these dudes when they come back or before they go on deployment. Now I get the opportunity to give them more than I could while I was in."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.