Section Branding

Header Content

How a political standoff trapped hundreds of migrants at the Belarus-Poland border

Primary Content

A standoff between migrants and Polish border guards has become the biggest challenge to the EU's borders in years. The crisis appears to be stoked by the leader of Belarus over the country's tensions with the bloc.

Poland's defense minister said on Wednesday that the crisis at the border with Belarus, where thousands of migrants are trying to cross, could take months to resolve, even as there were signs that the confrontation might be ratcheting down.

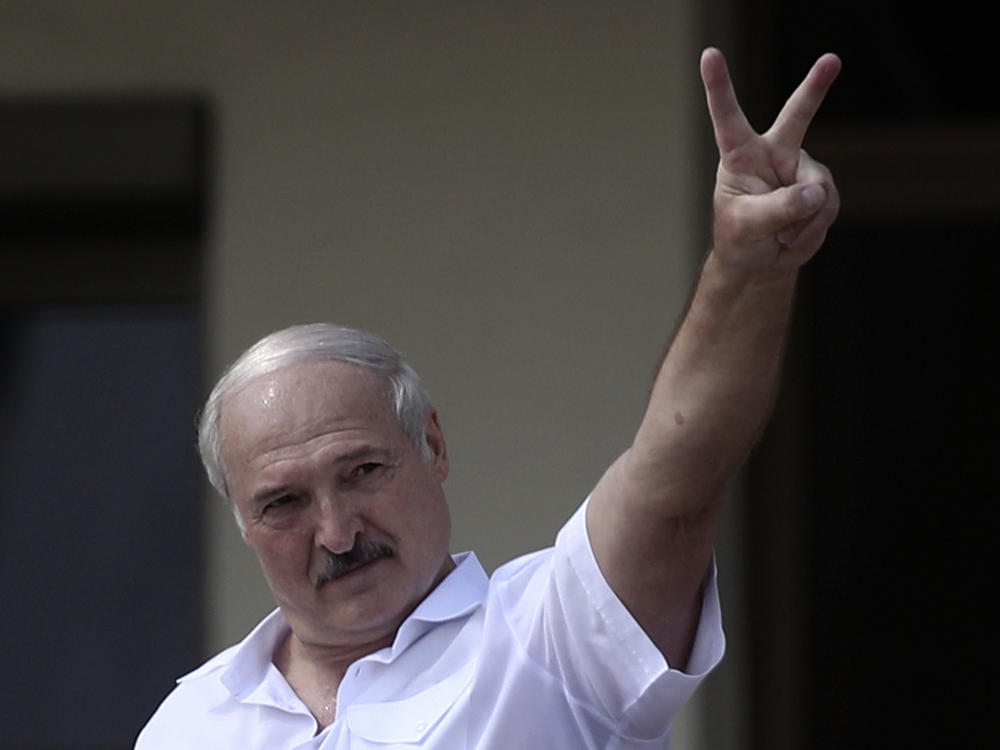

Although some have managed to cross the border with Belarus in recent weeks, Poland has now strengthened its border fence and closed crossings in response to what is widely seen as a manufactured crisis by Belarus' authoritarian president, Alexander Lukashenko, who is accused of using the migrants as pawns in a game of blackmail with the EU.

Here's a look at how the crisis started, and what Belarus appears to be trying to accomplish.

How did tensions ramp up at the border?

Since early this month, a wave of migrants from Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan and other countries, have been camped in the sprawling Białowieża Forest at the border in freezing temperatures.

They are hoping to cross into Poland. Belarus has been accused of encouraging migrants to fly to its capital Minsk, before pushing them toward the border with Poland, and even encouraging them to clash with Polish authorities. It's a charge than Lukashenko's regime has denied.

The standoff has seen Polish border guards using water cannons and tear gas this week to turn back stone-throwing migrants on the Belarus side. Belarus is not a European Union member, but Poland is. For the migrants, Poland represents a doorway to the EU and the promise of a better life.

Although only about 3,000 to 4,000 migrants are trying to cross, it has become the biggest challenge to the EU's borders since 2015, when hundreds of thousands of migrants gathered in Turkey to cross over into Europe. More than a million migrants were eventually allowed into the bloc.

"It's a terrible situation," for those caught in the forests without food or proper clothing, says Hanna Liubakova, a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council's Eurasia Center.

Many of them were lured there by Belarus, the EU says. Liubakova tells NPR that tourism agencies in Belarus have offered promises that "it would take only a few hours to get through the forest and swamps," to cross the border. For most, she says, Poland is seen as only a first stop in the EU. They are hoping to settle in countries such as Germany.

Several migrants trapped at the border and living in the open or in makeshift tents have died in the freezing conditions.

People are being "duped" says Emre Peker, the Europe director at the Eurasia Group, a consultancy.

"Some are coming from war-torn places. Some are coming from not so ideal backgrounds and circumstances," Peker tells NPR. "They're paying good money to take that risk and to try and make a make a better life for themselves."

Last month, NPR spoke with two migrants from Cuba, Doniel Machado Pujol and Raydel Aparicio Bringa, who said they'd survived on river water and kernels of raw corn and slept under piles of leaves before they were apprehended by Polish police.

"We flew from Havana to Moscow, and then a man picked us up and drove us to Belarus, and that's where our journey got a lot worse," Machado Pujol, injured and malnourished, told NPR's Rob Schmitz.

Russia is a close ally of Belarus, and Moscow is "a significant transit hub," Peker says. "Russia has so far not shown any desire or willingness to scale back flights to and from the Middle-East and Minsk to sort of curb the arrival of these would-be migrants."

This week, Polish guards used water cannons and tear gas against stone-throwing migrants at the Kuznica-Bruzgi border crossing. These are the kind of scenes that appear to play into the hands of Lukashenko, who is angry at the EU for sanctions imposed on his regime in the wake of Aug. 2020 elections.

What does the leader of Belarus hope to accomplish?

Lukashenko, who has held power in Belarus for more than a quarter century, was returned last year for a sixth-term as president in a vote widely viewed as fraudulent.

What followed was a violent crackdown on dissent amid anti-government demonstrations that followed the fraudulent poll.

In May, Belarus forced an international flight to land in the Belarussian capital of Minsk so that authorities there could arrest journalist Roman Protasevich, the former editor and founder of an opposition blog and social media channel, who was aboard the Ryanair jet.

The brazen act prompted the EU to impose retaliatory sanctions. Shortly after, Lukashenko then hinted at his ability to quickly gin up a migrant crisis against his EU neighbors — Poland, Lithuania and Latvia.

"Lukashenko wants to show his revenge for sanctions," says Liubakova of the Eurasia Center. But the leader also wants to switch the discussion from political prisoners, torture and repression under his rule to something external, she says: "He wants to focus to refocus the situation and force the West to see the crisis at the border and ignore the human rights situation in Belarus."

But the Belarusian leader — a virtual pariah except for Russia — has also been diplomatically isolated since last year's election.

"His key aim is to restore contact with European leaders," Maxim Samorukov, a fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center, tells NPR.

"He understands force... and believes that [the EU] can be forced to restore dialogue," Samorukov says.

What can Poland and the EU do?

The EU is planning additional sanctions against Belarus in response to the migrant crisis. But since sanctions are a main reason that the situation has come to a head, it's not clear how much impact they would have.

Meanwhile, outgoing German Chancellor Angela Merkel discussed the situation on Monday with Lukashenko in a rare phone call between the two leaders. Germany would likely receive the largest influx of any new migrants if Poland opened its doors. She and Lukashenko agreed that the situation needed to be defused, but Lukashenko said he and Merkel did not see eye to eye on how the migrants got to Belarus, according to Deutsche Welle.

Their talk appears to have helped de-escalate the situation at the border amid reports that Belarus is putting migrants on buses to be transported out of the area.

Merkel also spoke with Russian President Vladimir Putin, asking him to use his leverage on Lukashenko.

So, Lukashenko has succeeded in re-opening dialogue, but it's unclear where that might lead, given continued international distaste for his heavy-handed and undemocratic tactics.

Meanwhile, the fate of the migrants is also unclear.

Jan Egeland of the Norwegian Refugee Council tells NPR's Morning Edition that "both sides of this abject power play should take responsibility for these migrants, who are vulnerable people."

"They are men, women and children that have now come in some kind of a political crossfire," Egeland says. "The European Union and Poland are obligated to hear the case of asylum-seekers. That's international law. And Belarus and Russia have to stop this using them as pawns on some kind of a chessboard."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.