Section Branding

Header Content

Poop sleuths hunt for early signs of omicron in sewage

Primary Content

Scientists have detected traces of omicron in wastewater in Houston, Boulder, Colo., and two cities in Northern California.

It's a signal that indicates the coronavirus variant is present in those cities, and it highlights the useful data produced by wastewater surveillance research as omicron looms.

Gathering this data requires careful collaboration among wastewater facilities, engineers, epidemiologists and labs. Scientists and public health officials say the data derived from samples of feces can help fill in the gaps from other forms of surveillance and help them see the big picture of the coronavirus pandemic, especially as a new variant emerges.

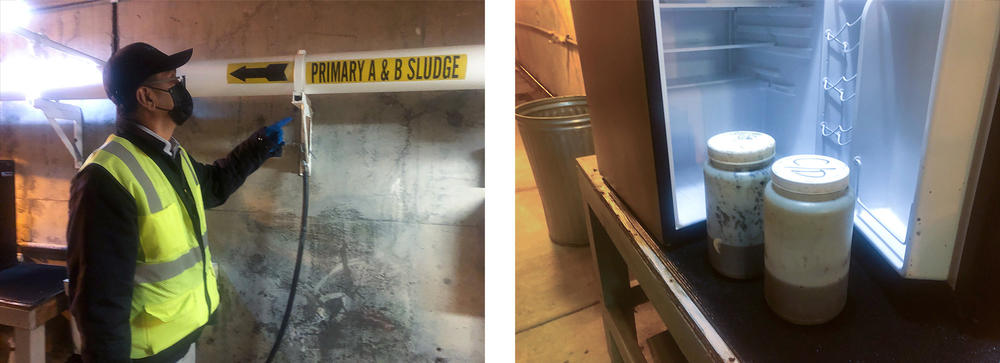

In San Jose, Calif., it all starts in a tunnel under the San José-Santa Clara Regional Wastewater Facility, which processes sewage from about 1.4 million people and 22,000 businesses.

Chances are that in many parts of Silicon Valley, what goes down the toilet ends up at this large plant at the south end of the San Francisco Bay.

"Every time you flush, think of us," said Deputy Director Amit Mutsuddy as he gave a tour and cursed the seagulls that feed on the fat floating on top of raw sewage settling in long tanks.

Staff members here retrieve samples daily as part of their regular lab work. They send additional test tubes by courier to get tested for the coronavirus at an outside lab that partners with Stanford University and the Sewer Coronavirus Alert Network (SCAN).

The SCAN project tests wastewater from plants around Northern California. It's only one of many on the hunt for the coronavirus, including omicron, in wastewater across the U.S. and around the world.

If there are strands of omicron RNA in that gunk, researchers can identify omicron at concentrations as small as one or two infections out of 100,000 people.

"As you can imagine, thousands of different kinds of diseases exist in the sewer. We work with them safely," Mutsuddy said. "It has not been anything new for us. It's just another coronavirus."

Taking a sample involves dodging suspicious-looking puddles in a dimly lit tunnel that runs underneath the smelly tanks. Along a long hallway, there's a sink where the faucet spews globs of black sludge.

What settles to the bottom of the tanks is called primary sewage and contains the solids that go down the pipes when the toilet gets flushed. Mutsuddy said it's easier to find virus there.

"The virus is lipid based, so it tends to stick to the fatty surfaces of solids," Mutsuddy said. "That's where we thought would be the maximum potential for capturing the virus if there is a trace of its RNA."

This is step one of an important new early-warning system to understand the spread of the omicron variant, said Dr. Sara Cody, the health officer for Santa Clara County, where the San Jose plant is located.

"It makes sense to broaden our perspective and have many different surveillance tools spinning. We've seen which ones really bore fruit," she said. Wastewater surveillance "is one that has ended up being really helpful."

A lucky break with omicron's mutations

Last week, researchers flagged four samples from wastewater plants in Sacramento and Merced for genetic mutations that looked like omicron.

Stanford environmental engineering professor Alexandria Boehm said her team's first findings had some uncertainty while they hurried to recalibrate their testing to spot omicron RNA, rather than delta. There was a small chance that their tests were picking up on another rare variant.

But they caught a lucky break: Omicron has a mutation in common with the alpha variant, which had been circulating several months ago. So they swapped out for older tests and spotted mutations characteristic of omicron.

After another round of omicron-specific tests on Monday, Boehm was more sure. SCAN announced the discovery.

"Because we detected it with two different assays that target two different mutations in omicron, and since they were both detected, I'm very, very sure that omicron is present in the wastewater samples," she said.

So far, the variant isn't showing up in clinical data in Sacramento and Merced counties. Public health officials have not identified omicron cases in those counties from PCR tests. In California, labs sequence about 20% of positive nose swabs, and that can take weeks.

But even the initial assays from the sewage were enough to notify county public health officials in Sacramento and Merced that omicron is present in their communities.

Boehm and her colleagues are confident in their testing — omicron is there — but they're not yet saying these four positive wastewater samples show community transmission of omicron, because that would require more data over a longer period of time.

"We're going to keep looking at it in these communities. If we see it continue to be present and start to go up, it's a really good indicator that it's circulating," said Krista Wigginton, an environmental engineering professor at the University of Michigan and another lead researcher on the project.

The team has seen steady concentrations of coronavirus RNA in Sacramento over the last two weeks and declining concentrations in Merced.

Searching the "alphabet soup" of sewage sludge

The fact that researchers found the variant at all represents a leap in testing capabilities and wastewater surveillance technology.

Cell biologist Tyson Graber, who's part of a team that monitors wastewater for the coronavirus in Ottawa, Canada, compares wastewater testing to looking at an "alphabet soup" of RNA from all kinds of organisms in the sludge and trying to recognize sentences that describe coronavirus variants.

"Thankfully we do know the language," he said.

The challenge is that the RNA "letters" are combined with everything else that passes through your body, plus last night's pan drippings that got scraped down the kitchen sink — then multiply that by about several hundred thousand other people.

"We really understand the language of SARS-CoV-2 now at a rate that's unprecedented in biomedical research history," said Graber.

The testing is both specific and sensitive. Plus, it's quick, he said.

"It's almost in real time. The turnaround time for our test for the alpha variant was under eight hours. This provided us a bit of a lead time in telling the community, 'Watch out: This new variant is here. It's increasing at this particular rate, and you should be watching yourselves and reducing your contacts.' "

Cody, the health officer in Santa Clara County, which has not yet detected omicron in PCR tests or in wastewater, said the beauty of wastewater surveillance is that everyone in a given area gets tested.

Like the children's book says, everyone poops. Everyone contributes almost daily samples.

Wastewater surveillance is a way to make up for deficiencies in other forms of testing. The data it captures includes people who are infected but don't have symptoms or don't get tested, as well as people taking at-home rapid tests, as they become increasingly available.

"If people aren't going out and getting a PCR test, those results in those cases aren't reported to us, and we won't see them in our case surveillance data. But we will still see it in our wastewater data," she said.

Santa Clara County has more than a year's worth of wastewater data to compare with results from PCR tests. Cody says they've learned when clinical data trends track wastewater concentrations.

"We started to see an uptick in a number of our sewer sheds just a little bit ago, and now we are beginning to see an uptick in our case count. So I think it gives us information a bit earlier," she said.

Copyright 2021 KQED. To see more, visit KQED.

Correction

An earlier version of this story misstated Tyson Graber's first name as Tyler.