Section Branding

Header Content

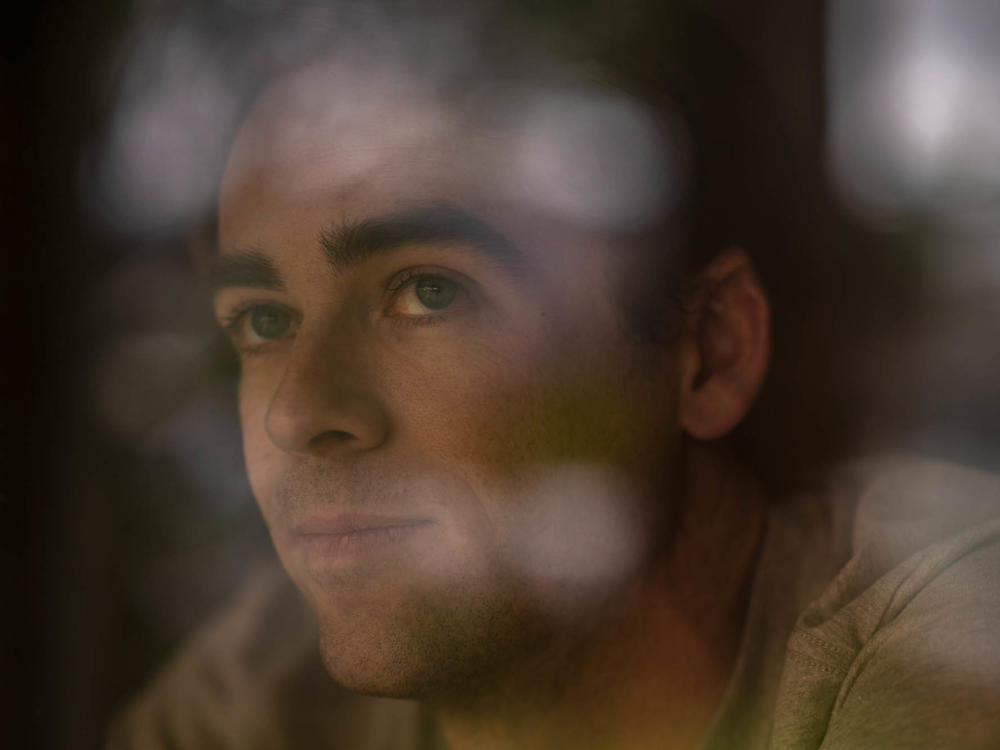

Theranos whistleblower celebrated Elizabeth Holmes verdict by 'popping champagne'

Primary Content

When Elizabeth Holmes jury deliberations entered its second week, Tyler Shultz got the jitters.

"I decided to deal with it by playing my guitar superloud. I probably disturbed my neighbors," said Shultz, an ex-Theranos employee who helped expose the once-hyped blood-testing startup. "I had a lot of nervous energy."

For Shultz, the moment had been building for some time. He blew the whistle on Theranos when he was just 22 years old. Now 31, he was ready for closure.

"This story has been unfolding for pretty much my entire adult life," said Shultz in a long-ranging interview with NPR from an in-law suite at his parents' home in Silicon Valley's Los Gatos.

On Monday, his phone buzzed with a message from his wife, he said, "It was a text in all caps: GUILTY."

The jury had convicted former Theranos CEO Holmes on four charges tied to investor fraud. Jurors also acquitted her of four counts related to patient fraud. The panel was deadlocked on three other investor fraud-related counts.

To Shultz, it was something else: the end.

"All of a sudden, it was just a weight was lifted," Shultz said. "It's over. I can't believe it's over."

And that, he said, was worthy of a bubbly toast with his mom, dad, brother and some friends.

"My family said, 'Come on down we're popping champagne. We're celebrating,' " he said.

Shultz was not the only Theranos whistleblower, but he was the first to report troubling findings at the company to regulators. At the time, it was a risky and bold move, and it came at a high cost for Shultz. But it helped accelerate scrutiny that would ultimately end with the company's implosion.

From inspired to disillusioned: Shultz's Theranos story

It all started in 2011, when Shultz was just a college student. He was visiting his grandfather, the celebrated former Secretary of State George Shultz, at his home near the Stanford University campus.

His grandfather wanted him to meet someone. Her name was Elizabeth Holmes.

"She was wearing her all-black outfit, turtleneck. She had those deep-blue, unblinking eyes. I heard her deep voice," he said, describing attributes that came to define the charismatic tech executive.

When she started talking about Theranos, a company she dreamed up at 19 in a Stanford dorm room, Shultz's curiosity was piqued.

The idea was to make blood testing faster and easier and less painful with just a finger prick — all done on an innovative device that Holmes invented called the Edison. Shultz, a biology major, wanted to be part of that revolution.

"She instantly sucked me into her vision, and I asked her, 'Is there any way I can come work at Theranos as an intern after my junior year?' "

And he did. Eventually, he became a full-time employee. But it would only be eight months after getting hired that he would resign.

Shultz had worked countless hours in labs. Armed with this scientific know-how, he quickly realized something was amiss when he looked inside of the Edison device.

"There is nothing that the Edison could do that I couldn't do with a pipette in my own hand," he said.

Then he discovered another alarming thing: When Theranos completed quality-control safety audits, it was running tests not on the Edison, but on commercially available lab equipment. That did not seem right.

"It was clear that there was an open secret within Theranos that this technology simply didn't exist," Shultz said.

This emboldened Shultz to blow the whistle. He contacted state regulators in New York using an alias. He worked with then-Wall Street Journal reporter John Carreyrou to reveal Theranos' shortcomings and exaggerations.

"I would not have been able to break this story without Rosendorff, Tyler and Erika," Carreyrou told NPR, referring to Shultz and two additional Theranos whistleblowers, Adam Rosendorff and Erika Cheung. "Tyler and Erika were corroborating sources, and that was absolutely critical."

For Shultz, it was not the path of least resistance.

"It would have been easier to quietly quit and move on with my life," he said. "And that's actually exactly what my parents advised me to do when I was a 22-year -old kid fresh out of college."

But he insisted on the harder path. And that involved confronting his grandfather, a legendary statesman who had a seat on the Theranos board.

"He didn't believe me. He said Elizabeth has assured me that they go above and beyond all regulatory standards," he said. " 'I think you're wrong' is what he told me."

It took some time for the elder Shultz to come around and believe his grandson. Their relationship was never the same and he never apologized.

"But he did say I did the right thing," Tyler Shultz said.

Shultz warned his famous grandfather: Hold Holmes accountable

Many of the marquee names that made up the Theranos board — former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, former Defense Secretary William Perry, former Sen. Sam Nunn — were recruited by Shultz.

And Tyler Shultz made repeated attempts to try to salvage his grandfather's legacy, though he kept being rebuffed.

"I said, 'I know you brought all your friends into this, and you feel like you need to stay there to protect your friends, but there's still an opportunity for you to get them out too,' " he said. " 'You can lead the way for the board to do the right thing and hold Elizabeth accountable.' "

George Shultz, who has since died, would not be persuaded at the time.

For the younger Shultz, having a falling-out with his grandfather was just the beginning. Being a Theranos whistleblower would soon morph into a much bigger nightmare. Soon, he was dealing with private investigators Holmes hired to follow him. Lawyers tried to intimidate him. Holmes tried to destroy his life.

Shultz watched the Holmes trial mostly from afar, reading social media and news coverage, from his San Francisco apartment.

He did show up once, however, during closing arguments and sat in the courthouse's overflow room. He said it provided him with some closure to be able to see the trial live.

"I just wanted to listen to the closing arguments and make it feel real, rather than watching your life through a Twitter feed," he said.

Still, he did not want to create a scene.

"I had a jacket on. I had my hood pulled down past my eyes so nobody would recognize me," he said.

Reporters eventually recognized him, but he didn't want to share his thoughts until there was a verdict.

Think the blood test works? Prick the judge

These days, Shultz is running his own biotech startup focused on women's fertility issues. He is pitching investors and making grand promises.

"I'm under pressure to exaggerate technology claims, exaggerate revenue projection claims. Sometimes investors will straight-up tell you, you need to double, quadruple, or 10x any revenue projection you think is realistic," he said.

In a weird twist, the experience has him comparing himself to his now-notorious former boss.

"I could see how this environment could create an Elizabeth Holmes," Shultz said.

Shultz was on the government's witness list. He was never called to testify. He isn't sure why.

"I guess my emails just spoke for themselves," he said.

But he did imagine a scenario, partially in jest: that if he were summoned to court, he would appear with the Edison device.

"Let's prick the judge's finger and see what happens," said Shultz, laughing. "And it wouldn't work. I knew with 100% confidence that would never happen. They would never be able to prove me wrong."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.