Loading...

Section Branding

Header Content

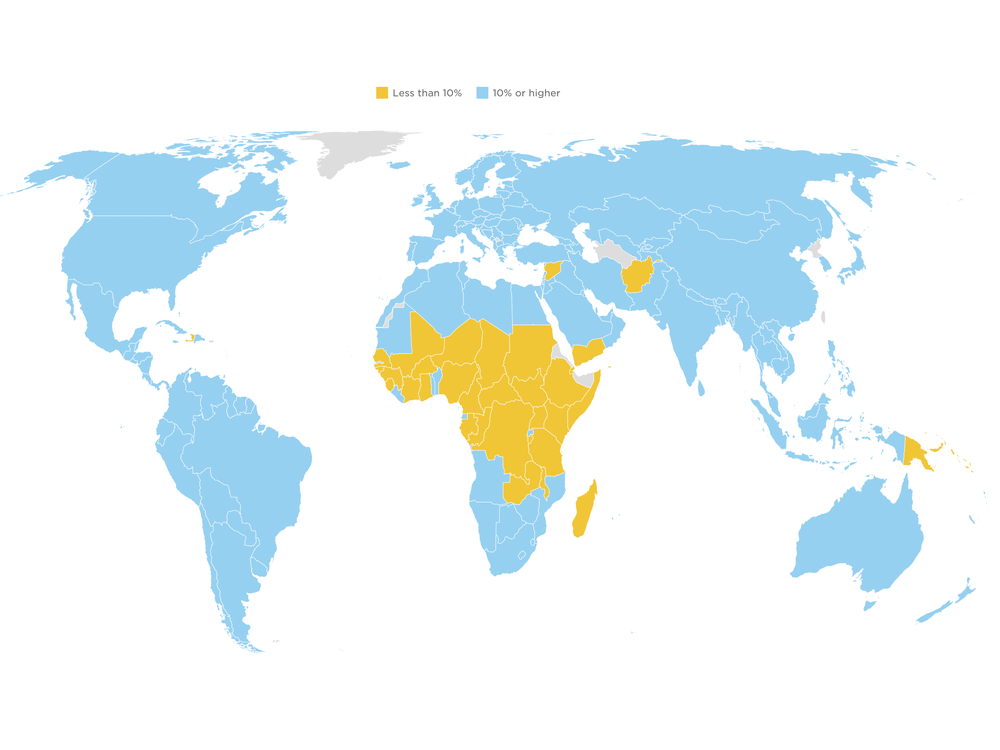

For the 36 countries with the lowest vaccination rates, supply isn't the only issue

Primary Content

In the United States and many other wealthy countries, you can get a free COVID vaccine at supermarkets, pharmacies and clinics.

In other countries, it's a very different story.

"The vaccine is not available in the North (of Yemen)," says Jasmin Lavoie with the Norwegian Refugee Council, who's based in the northern city of Sana'a. "If a person wanted to be vaccinated, that person would have to go to the south. So drive around 15 to 20 hours crossing front lines in the mountains." Even then, after such a treacherous journey through a war zone, it's not clear if doses would be available. Like many low-income countries, Yemen has struggled to get hold of vaccine.

"Yemen has been one of the places with the lowest vaccination rates in the world," says Lavoie. "And that's despite the fact that we've experienced three waves of COVID." Currently fewer than 2% of Yemenis are fully vaccinated.

Yemen is one of 36 countries that fall below the 10% immunization threshold, some with rates under 2%. Much of the mid-section of Africa is in that category, including powerful economic and political players like Kenya, Nigeria and Senegal.

By contrast, many wealthy countries have fully vaccinated more than 80% of their citizens.

Why Africa lags so far behind

Maaza Seyoum with the African Alliance, a South Africa-based advocacy group, says there are many factors playing in to the low vaccination rates in many countries on the continent but the biggest issue is simply that African nations have struggled to get doses.

"Initially, 100 percent, I would say the problem was a lack of access (to vaccines) and a global system that did not prioritize African countries," Maaza says. Wealthy nations bought up far more pharmaceutical firms vaccine production than they could even use. The WHO-backed COVAX program faltered as it relied heavily on voluntary donations and on manufacturers in India who were blocked from exporting doses when COVID case numbers skyrocketed on the sub-continent. Some African countries managed to get supplies from China but Beijing often prioritized donations to wealthier trading partners.

That situation has changed, says Maaza. Recently vaccine deliveries to Africa have increased. But now there are new problems: the shipments are haphazard and sometimes consist of less popular brands that are about to expire.

"Now we're seeing the sort of drip, drip, drip of vaccines," she says. "People are waiting for vaccines to come. They come, then they stop."

This unpredictable supply chain, she says, makes it nearly impossible for African countries to plan nationwide vaccination drives. And in some of these places where hardly anyone has gotten the jab, rumors about the mysterious vaccine have flourished and augmented vaccine hesitancy.

"The truth is, there is vaccine hesitancy everywhere," Maaza says. "But as people are waiting, it leaves kind of a fertile ground for these rumors to circulate."

Which makes convincing people to come to a clinic and get immunized even more of a challenge.

What's behind those under 10% vaccination numbers

The World Health Organization set a goal of trying to push all countries to 40% vaccine coverage by the end of 2021. The 36 countries still under 10% obviously didn't even get close. Kate O'Brien, the director of immunization and vaccines for the World Health Organization, says this is a significant problem.

"For countries that are struggling to get even above 10%, what this means is that health-care workers are not fully vaccinated yet," she says. "It means older age populations, those who have underlying medical conditions, the people at highest risk are not fully protected yet."

She acknowledges vaccine supply inequity as a major part of why rates are so low in these three dozen countries but says there are other reasons too. Many of these countries had health systems that were struggling even before the pandemic to meet local medical needs. Some of them have needed to upgrade refrigeration systems to be able to store certain mRNA vaccines at extremely low temperatures. Others need syringes. All of this takes money that many low-income nations health ministries may not have.

"A COVID vaccine campaign does require funding," O'Brien says. Countries need money "to deploy new health workers and to assure that the clinics have the resources that they need."

And while there has been some international assistance to lower-income nations to help, that financing has also at times been haphazard and unpredictable.

Ongoing conflicts present another obstacle

Away from Africa, the other nations that haven't yet gotten above 10% COVID vaccine coverage are some of the most troubled in the world, including Yemen as well as Syria, Afghanistan and Haiti.

Currently the armed conflict has displaced 4 million of 30 million Yemenis from their homes. Various groups control different parts of the country. According to the U.N. more than 2/3rds of the population is in need of humanitarian assistance. Yet international aid agencies have struggled to meet those needs and keep their operations running in the country due to the ongoing insecurity and a lack of funding.

For most people in Yemen, life is incredibly difficult. COVID vaccinations are "not on the top of the list of priorities for many people in Yemen," Jasmin Lavoie with NRC says. He says most Yemenis spend their days trying to find food, shelter, decent toilets and worrying about whether they'll have to flee fighting once again. "These are reasons why people are not getting vaccinated too," he adds.

There are similar issues in other conflict zones. "In a place like Afghanistan, in a place like Syria, COVID is not their number one priority," says Paul Spiegel, who runs the Center for Humanitarian Health at Johns Hopkins University.

Spiegel returned to Baltimore from working in Afghanistan in mid-December. "[Vaccination] campaigns are happening," he says but adds that the immunization drives are constrained by the limited shipments of vaccine. "A fair bit of it is Johnson and Johnson, which makes a lot of sense in Afghanistan situation because it's just one dose," he notes.

But similar to Yemen, the social upheaval in Afghanistan, with the U.S. departing and the Taliban returning to power, has pushed COVID to the backburner. Vaccine drives are not a top priority for the Taliban, even though it has said it supports vaccination drives by COVAX and the U.N.

Nor is it a priority among Afghans. "Right now there's such a dire humanitarian situation there," he says. "[Afghans] are worried about getting food on the table, they're worried about feeding their kids. And so COVID is not a priority for the average person."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.