Section Branding

Header Content

Heartbroken? There's a scientific reason why breaking up feels so rotten

Primary Content

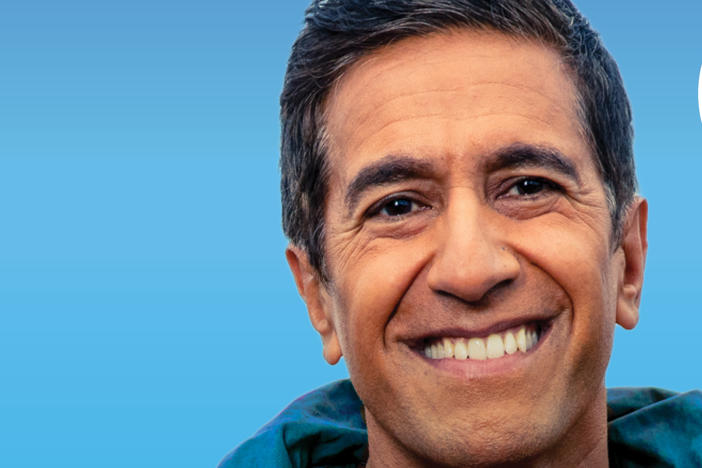

Science writer Florence Williams experienced what felt like a brain injury when her husband left her after more than 25 years. Her new book is Heartbreak: A Personal and Scientific Journey.

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Heartbreak can make you physically ill. Take my guest, science journalist Florence Williams - when her husband left her after more than 25 years, they had to devise a plan for co-parenting. And she says physically, she felt like her body had been plugged into a faulty electrical socket. She lost 20 pounds. She'd stopped sleeping. She developed diabetes. It was hard to think straight. She wanted to understand why the emotional upset she was experiencing was also causing her body and brain to malfunction. She found in recent years science had begun to investigate the biological pathways of this brand of pain. She traveled across the U.S. and to England to report on researchers investigating how and why emotional pain can lead to physical pain and illness. Her new book is called "Heartbreak: A Personal And Scientific" Journey. Her previous book, "The Nature Fix," is about the science behind why being in nature can make us healthier. She was previously on our show to talk about her book "Breasts: A Natural And Unnatural History," which tried to answer such questions as, why did chemicals like flame retardants show up in her breast milk?

Florence Williams, welcome back to FRESH AIR.

FLORENCE WILLIAMS: Thank you so much, Terry. It's great to be here.

GROSS: Let's start with your marriage, just so we understand the circumstances leading to the heartbreak. How did your marriage dissolve?

WILLIAMS: The relationship with the man who would become my husband started when I was 18 years old on literally my first day of college. Seven years later, we got married, so we were together actually a total of 32 years or my entire adult life. And then, you know, I guess the start of the dissolution really came when one evening before friends were coming to dinner, he handed me his phone to look at an email from his brother, only there was a different email on his phone, and it was a love note to another woman. And I would say that that was probably the worst night of my life. I was in the middle of the email reading the email when the friends walked in the front door, so I had to kind of plaster a smile on my face and get through this dinner before I was able to really investigate a little bit further. I found some more emails. And then he went to Alaska for two weeks, so it was a couple of weeks before we could actually really talk about it. And it was clear to me at that point that if my marriage wasn't over, it was about to be very, very different.

GROSS: That email mess up seems to be such a common thing. I mean, it's even in so many movies and TV shows. It makes me wonder, like, how many marriages have - and relationships - have ended that way.

WILLIAMS: I think it's very hard these days to disguise any kind of affair, whether it's emotional or physical. And in his case, the affairs - there were two - they were really emotional affairs. They weren't physical affairs. So I do want to make that distinction. Although it kind of hits your brain and your heart in a similar way, as I found out.

GROSS: So when you did separate, what did that mean for you emotionally? Like, how did that change your life? You'd been together since your first day of college.

WILLIAMS: I can almost describe it like a brain injury, that you have to relearn how to do everything because the way that you move through the world and the way that you operate in space and time is totally different. You know, my social self I felt like had just kind of dissolved, my public self and my private self. The artifice and trappings and comforts of sort of moving through the world as a married person were now gone. And I really didn't know how to move through the world as a single person. And I know to single people hearing that, that probably sounds ridiculous. But all I can tell you is it felt like a total reassessment of everything I knew about myself.

GROSS: Had you ever lived alone?

WILLIAMS: I had never lived alone. You know, as I said, I met him when I was 18. I mean, there were periods of time, I guess, when we lived apart, but he was always sort of there even - you know, he was there emotionally if he wasn't always there physically. And now he was neither.

GROSS: One of the things you learn is that a couple really functions as a unit. The bodies can actually sync up. What does that mean?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, your bodies really co-regulate when you live in such close proximity and in an intimate way with someone. So your heart beats actually regulate. You know, when you're asleep, your cortisol levels line up, sort of your morning and evening cortisol levels. Your respiration rates sometimes align. And there are a lot of studies showing that when you put a couple in a brain scanner and you give them a task, their brain waves actually sync up in the same way. So they go into sort of the same sine wave patterns. Whereas if you put one of those people in a scanner with someone they don't know very well, that doesn't happen.

GROSS: So what happens when one of the people in a couple leaves and you're not syncing up with that person anymore? What does that do to your biology?

WILLIAMS: Your brain and your body really notice it in a subconscious level. So your cortisol levels go way up. They're sort of like, where's my mate? Where's this person who I'm used to co-regulating with? Something's wrong. These alarm systems go off in your body because your nervous system suddenly feels like it's under threat because you're alone. And humans are such social animals. We're even, you know, hyper - people call us hyper social animals, that when we're alone in a deeply evolved sense, we don't feel safe. You know, we know that to be alone in the jungle means we're more likely to face a predator. We're more likely to get injured. Our nervous systems do not like being alone. I think eventually, you know, we can get comfortable with it and learn how to do it. But when there's a dramatic shift like that, we do feel on some level unsafe.

GROSS: So when did you realize that your heartbreak wasn't just emotional, that you were having physical symptoms, that it was having a bad effect on your body?

WILLIAMS: Well, I started having physical symptoms right away. I mean, even, you know, from the moment I read that email, I felt like something really repositioned itself, you know, where my stomach was in my body. And that's partly the release of these stress hormones. You know, when you're in sort of an acute phase of stress, you have this kind of hypervigilance that sets in. And that's, again, sort of a threat-based state. So you're looking over your shoulder and you're not sleeping well, and your body is gearing up for some sort of threat.

So for me, I wasn't sleeping at all. I felt really agitated. You know, I think you mentioned that I felt like I'd been plugged into a faulty electrical socket. I eventually, you know, got some lab work done and found out that my glucose levels, my blood sugar levels, were way off. My gut bacteria was way off. And eventually, you know, some months later, I was diagnosed with early stage adult onset Type 1 diabetes, which is an autoimmune disease.

GROSS: Are there scientists who are literally studying heartbreak or is heartbreak just part of, like, a larger set of emotions that researchers are studying to try to understand how that kind of emotional upset can lead to physical upset?

WILLIAMS: You know, I think in the field of psychology, researchers have been looking at divorce and heartbreak, you know, in some interesting ways. And some researchers are putting heartbroken people or, you know, dumped people in brain scanners and seeing what's going on with their brain waves. But recently now, there are scientists who are looking at a sort of more cellular genetic level for epigenetic changes, not so much specifically linked to heartbreak but linked to loneliness. We know that loneliness is a major risk factor for a number of diseases and for early death. And we also know that divorce and relationship loss is considered a major risk factor in itself for loneliness.

GROSS: So some of the researchers you spoke with are using fMRI. That's functional MRIs. In other words, they can look at what part of the brain lights up when something happens to you. So they're trying to see what part of the brain gets activated when you're feeling emotional loss or whatever. So tell us about one of those fMRI studies that you found especially interesting and relevant.

WILLIAMS: So pretty early on after my own separation, I was fortunate to run into biological anthropologist Helen Fisher. And in 2011, she did some really interesting studies in an MRI looking at the brains of people who had been dumped by their partners. And what she found was that parts of the brain were activated that are associated with addiction and craving because people were still yearning for and missing their lost partners. And since then, other researchers in MRI studies have found that the social pain of heartbreak winds up somewhat closely with parts of the brain that process physical pain, showing that social pain is taken as seriously in our brains as physical pain - produces all kinds of signals that change our behavior. And perhaps in some ways, you know, there's an evolutionary reason for this - you know, reason for why we feel heartbreak so carefully and so intensely. And the brains of these are really backing that up.

GROSS: There are studies of the neurotransmitters that are released when you fall in love and feel real good compared to the ones that are released when a relationship ends and you feel really bad. Can you talk about that a little bit?

WILLIAMS: Yeah. Helen Fisher loves to talk about falling in love (laughter). And she mentions the amazing sort of rush we get from the dopamine of, you know, flirting with someone, making connections with someone and then, of course, the oxytocin that's released when we have a physical relationship with them or when we touch them or even look deeply into their eyes. Women especially tend to release a lot of oxytocin. Men release vasopressin, which is a hormone associated with mate-guarding and homebuilding and sort of emotional commitment. When that love disappears, there's a flood of stress hormones. These drive this feeling of, you know, adrenaline and sort of that amplifier feeling of being really plugged in. And there's this drop, this sudden drop, in serotonin and in dopamine that leaves us feeling really empty and flat and missing the rush of love.

GROSS: So the neurotransmitters that help make you feel good are decreased, and the ones that make you feel bad are increased. Is that - (laughter).

WILLIAMS: That's right. And one of the most interesting things I learned about this is that when we fall in love, the parts of our brains that produce stress hormones - the sort of machinery for making those stress hormones - actually increase. So it's almost like the guns are loading (laughter). They're sort of ready to release stress hormones when we fall in love, which is weird. Like, why would the brain make more machinery to feel stress? And it may be because it's there for heartbreak so that when our partner leaves or sort of disappears, we get so agitated that we're motivated to go find them or to feel so grateful when they come back. And this is - you know, not just in humans, but this is in other mammals as well. So in a weird way, it's like falling in love sort of changes your brain, and it puts a loaded gun to your head. It's almost getting ready for heartbreak.

GROSS: We need to take a short break. So let me reintroduce you. If you're just joining us, my guest is Florence Williams. She's the author of the new book "Heartbreak: A Personal And Scientific Journey." We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF THE MOUNTAIN GOATS SONG, "PEACOCKS")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my interview with science journalist Florence Williams. Her new book is called "Heartbreak: A Personal And Scientific Journey."

As part of your research on the connection between emotional and physical pain, you had blood tests, but they - it sounds like they weren't, like, ordinary blood tests. They were molecular blood tests. What does that mean?

WILLIAMS: One of the most interesting conversations I had early on was with a neurogeneticist named Steven Cole, who works at UCLA. He's become a specialist in how our immune systems react to our social state. So he told me about these studies that he did a long time ago looking at men - gay men with HIV. And these were really eye-opening studies because what they showed was that the men who felt like they had less social support actually advanced to full-blown AIDS much earlier, and they died earlier than the men who felt like they did have social support. And then he started studying healthy people who identified as being lonely, again, to sort of figure out, why was it that lonely people seemed to die earlier and suffer from more chronic diseases?

And he found changes in a set of genes - and specifically in the transcription factors in these genes - that prepare their immune systems to respond to certain kinds of threats and not to respond to other kinds of threats. And it's (laughter) very - it's a very long story. But basically, the gist of it is that when we feel alone and sort of abandoned, our bodies are gearing up for some kind of threat - for example, a predator or an injury. And so our bodies respond to that by producing more inflammation and immune cells that produce inflammation. And at the same time, they downregulate cells that, for example, fight viruses because we're no longer living in groups where viruses are spread. But we're alone and more likely, perhaps, to get a flesh wound where we'll need the inflammation (laughter).

But unfortunately, that is not a very helpful response when you're living in a modern society, where there still are lots of viruses and where we actually can suffer from the chronic inflammation if it keeps happening, if we feel lonely over time. He told me all this. And I told him about my heartbreak. I told him I had just been diagnosed with diabetes. And I was really struggling to understand this connection between our emotional states and our immune systems. And he said, well, why don't you come in? And we'll look at your blood. And we'll analyze it. And then you can come back, you know, come back six months after that and come back six months after that. And we'll see if your immune system really is responding to your heartbreak. That was an invitation I couldn't refuse. And that's what we did.

GROSS: So the first time you tested your immune system, what results did you get? And how did that compare to subsequent tests?

WILLIAMS: The first test we did was - I would say - I think it was about five months after my split. The way he described it to me at that point was, yes, I did have a lot of inflammation showing up in my immune cells and in the transcription factors that govern the way those genes turn off and on. And I seem to also have some downregulation in those antiviral cells. He said to me, your transcription factors do look like those of a lonely person. And then I went on a big river trip (laughter). Having written the book "The Nature Fix," I thought, well, nature was really going to help me feel better. It's really going to clean up my leukocytes, my white blood cells. So we did another test after I got off of that river trip. And then we did another sample about six months after that.

And the big disappointment for me was that after the river trip, which I was hoping would be the sort of great heartbreak cure, my cells looked just as bad, you know, pretty much. There wasn't a lot of change in terms of the way my body felt like it was in a threat-based state. And so that was disappointing (laughter). But, you know, by the final time point, after I had done a lot of other things in addition to just hanging out in nature, there finally was, actually, some real change. And that was wonderful to see.

GROSS: You know, that river trip you mentioned, that was an incredibly stressful trip.

(LAUGHTER)

WILLIAMS: It was (laughter).

GROSS: You went by yourself. It was a very rugged trip. You ran into a lot of problems, all kinds of problems, along the way. And a friend of yours said to you - I think you made a mistake. You did the kind of, like, macho kind of nature thing, as opposed to, like, the peaceful, beautiful (laughter) nature thing. So do you think that you actually created more stress with that trip?

WILLIAMS: Yeah. I think, you know, in retrospect, I probably didn't game that one very well. What I did was I wanted to do something dramatic. I had - you know, I had written in my book, "The Nature Fix," that three days in nature can really change your brain and, you know, improve your creativity and help you set life goals, you know, change your self-concept - all this stuff. So then I thought, well, this is a really big problem I'm having, my heartbreak. I don't need three days, I need 30 days. Let's just go for 30 days. So I spent - I found a river that I could spend 30 days on. It was the Green River in Utah. It's a really beautiful river. And so for about two weeks of that trip - I did it with friends and family members. My siblings were there. My kids came along on various parts of it. That part of the trip was really fun. But then I wanted to do this solo.

I felt like I needed to learn how to be alone. Didn't know how to be alone, I needed to make myself do it so I could be less afraid of it. I wanted to learn how to access bravery. I wanted to sort of feel like I was creating a new story for myself where I was literally paddling my own boat. And so - you know, the metaphors just seemed to line up perfectly with doing this kind of solo trip. Unfortunately, what I wasn't (laughter) taking into consideration is that when you're alone in the wilderness, you're not super relaxed. It's not a calm state. Yes, you can access bravery. Yes, you can learn how to be alone. Yes, you can do some deep thinking, but you're so hyper-aware of your surroundings. You can't make a mistake. You can't tie your boat in badly at night. You can't, you know, step on a thorn and, you know, get an infection. You have to just pay attention to everything around you and check off all these lists all day long, you know, so that you don't screw it up. And that's not a relaxing state. So in terms of, you know, how my body, how my immune cells were responding to feelings of threat, they really weren't going to change.

GROSS: Yeah. It sounds like instead of vigilance about your pain, your emotional pain, the vigilance was transferred to how to survive this trip.

WILLIAMS: Exactly. Exactly. If heartbreak is sort of the metaphor of, you know, feeling alone and unsafe, being in the wilderness is actually being alone and unsafe.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Good work. Good work, Florence.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Let's take another break here, and then we'll talk some more. If you're just joining us, my guest is Florence Williams. She's a science journalist. And her new book is called "Heartbreak: A Personal And Scientific Journey." We'll be right back after a short break. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "HOW CAN YOU MEND A BROKEN HEART")

AL GREEN: (Singing) And how can you mend a broken heart? How can you stop the rain from falling down? Tell me, how can you stop the sun from shining? What makes the world go round? How can you mend this broken man?

(SOUNDBITE OF GUY MINTUS TRIO'S "OUR JOURNEY TOGETHER")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my interview with science journalist Florence Williams. When her marriage broke up after 25 years, she was heartbroken. The emotional pain also registered in her body as physical upset. She lost weight, couldn't sleep. Her pancreas stopped working right. She wanted to understand why and how emotional devastation can mess up your mind and body. That led her to travel around the U.S., finding researchers investigating those connections. This wasn't just science journalism for her; it was an attempt to find ways she might recover from her devastating divorce. Her new book is called "Heartbreak: A Personal And Scientific Journey."

You know, your book is called "Heartbreak." The expression we use is, it's a broken heart. There's literally a heart disease that seems to be caused frequently, not always by heartbreak or emotional trauma of one sort or another. It could be a tornado. It could be a divorce. The disease - I don't even know exactly how to pronounce it - so takotsubo disease? Is that...

WILLIAMS: Yes, takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

GROSS: OK. What is it?

WILLIAMS: Yeah. You know, we used to think that heartbreak was just a metaphor. But people started noticing after a big earthquake in Japan that a lot of people were coming into the hospital with heart attacks, and these weren't people who had risk factors for heart attacks. They didn't have any blocked arteries. When their hearts were imaged, there were no signs of blockages or plaque breaking free. There was something about the traumatic event of that earthquake that released so many stress hormones that people's hearts actually kind of were stunned. They changed shape so that there was a lobe of the heart that was really distended and not able to pump very effectively.

So takotsubo is a Japanese word that means octopus pot, and it shows this sort of giant bulb where the octopus sits. So people's hearts were showing up with this weird, bulbous, distended shape. And now we know that takotsubo rates increase after natural disasters. They're especially common in postmenopausal women who have suffered a big emotional blow. So we see it in women whose spouses have died. We see it in women whose pets have died. There are some examples in the literature of men showing up with takotsubo after their sports teams are defeated, (laughter) if they're very, very invested in their soccer teams, especially. It's only about, I think, 5% of all heart attacks. But we now know that there's this very clear sort of emotional link between what's happened in your life and what's happening in your heart.

GROSS: Do people ever heal from that disease and their heart returned to normal?

WILLIAMS: They do. Actually, most people fully recover. A certain percentage of patients die. I think about 5% of patients die. Another 20% of patients will go on to have an increased risk of heart disease later in life. But most people do recover. And interestingly, I was describing takotsubo to a friend of mine, and she said, oh, I know someone whose boyfriend just left her and got another woman pregnant, and she heard this news and had a heart attack. And she's 41 years old. So I asked for her name, and then I got in touch with her. I asked if she'd be willing to tell her story, and she did. And that's in the book. And it was very dramatic. I mean, she really felt her heart seizing up. And I think a lot of us can sort of relate to that feeling of - when we're in the throes of grief, we do feel a constriction in our chest, in our hearts. So - and I think people have known for millennia, you know, that our hearts in some ways do really hold and process our emotions.

GROSS: You tried psychotherapy, too. Was that helpful? It's not about, you know, blood tests or anything, like, empirical. It's not about imaging your brain. It's about, you know, talking through and trying to understand yourself.

WILLIAMS: It was so helpful. My therapist was terrific. She - you know, she validated, you know, what I was experiencing. She validated my feelings. And she was really good about sort of calling my bluff, you know, when I was feeling like I was a loser, you know, and no one would ever love me again. And, you know, my self-esteem was so bottomed out, which is also a downstream effect of being rejected by love. You know, she would say things like, Florence, you are such a relational person, you know? You will find love again. I know you will. You know, the fact that you're 50 is - doesn't mean, you know, (laughter) that love is over. You know, I would get so, you know, anxious about sort of being older and being single. And maybe it helped that she was older than I am, but she was very comforting. And she just said, look; you know, you're going to look back on this, and it's all going to be OK. And just having someone tell me that and sort of tell me I was sometimes being an idiot was actually really helpful.

GROSS: Some people had said - and people often say this - don't rush into another relationship; you have to heal first. However, (laughter) you had a relationship pretty soon after, and when he started telling you what the safe word would be, you knew that this was not what you expected (laughter).

WILLIAMS: Not what I expected. It turns out my first relationship out of the gate was kind of an unfortunate one (laughter). You know, after - right after my marriage ended, I just thought, you know, I hate men. I'm just done with it. I'm just done, not interested. And I went to a conference, met a friend of a friend - really charismatic, you know, sort of cute, charming guy, also divorced. And we started flirting, and I was like, what is that? I haven't exercised that muscle in a really long time. It turned out to be kind of fun and kind of exciting. And by the end of the conference, we ended up actually making out under the moon, under a full moon in the mountains. And it just sort of blew my brain. I couldn't believe how turned on I was (laughter). And I was like, oh, right, that's why people still have relationships - because, you know, we are fully embodied sexual beings. And it was kind of wonderful to feel that.

Unfortunately, I think I associated that feeling also with, you know, wanting to be loved and wanting to be in a relationship, and I don't think he was terribly honest about telling me what sort of relationship he was looking for and also what particular sexual proclivities he had - and had to sort of learn all those things the hard way.

GROSS: Yeah. And I should say, this is after a friend said to you, there's no red flags with this guy (laughter).

WILLIAMS: He turned out to have several red flags. Oh, my God. Yes.

GROSS: Let's take another break here. If you're just joining us, my guest is science journalist Florence Williams. Her new book is called "Heartbreak: A Personal And Scientific Journey." We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF KEVIN EUBANKS' "POET")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my interview with science journalist Florence Williams. Her new book is called "Heartbreak: A Personal And Scientific Journey."

One of the things that you tried was psychedelics. You tried psilocybin and MDMA, which is ecstasy. I did. Why did you decide to try that?

WILLIAMS: I had a really, really almost life-changing conversation with a psychologist at the University of Utah named Paula Williams. And she said, yes, you know, people who are divorced have a much higher risk of all kinds of horrible things happening to them in terms of their health. But we know that some people are really resilient. And I was like, tell me about those people. I want to be one of those people.

GROSS: (Laughter).

WILLIAMS: What do I - you know, how do I become resilient? I had no idea if I was because I had never really experienced, you know, any kind of devastating loss like this. I really had no idea. And she said, what we have found, which is kind of a surprise that no one ever talks about, is that people who are really emotionally resilient, the ones who are able to tell these helpful stories about themselves are the ones who can experience beauty and the ones who can experience awe. And we think that this is because - this is what she would say. We think this is because - and we've seen this in brain studies - in the presence of sort of something really beautiful, our brains sort of make all these connections that they don't normally have. So all these neurons fire up in different parts of the brains because we're trying to understand what it is that's so beautiful in front of us. It's maybe something that we are not used to seeing, for example.

And if you're someone who can experience awe easily and even get goose bumps, you know, in the presence of a beautiful symphony or, you know, a mountaintop, that those are the people who seem to be more resilient after some really stressful life events. And I thought, OK, beauty. Now you're speaking my language, you know? I like nature. I like beauty. I like experiencing awe. I'm going to just do this as much as I can. So then I thought, OK, how else can I experience awe? And there was a lot of science coming out about psychedelic experiences, you know, really blowing people's brains, and perhaps even awe being the central emotion behind some of those revelations and experiences and healing that people were finding in psychedelic therapy. So I found a therapist who, you know, works in sort of a rigorous way. I interviewed a few. And she was great. So that's how I ended up in this woman's living room.

GROSS: What do you feel you came away with?

WILLIAMS: I went into those sessions with her with a couple of intentions. The main one was that I wanted to confront my ex and say goodbye to him, you know? I was having trouble letting go. I was having trouble letting go of who I was in the marriage, letting go of the marriage, letting go of my identity. And I was so afraid of the future. And during these psychedelic trips, I lost my sense of self. I felt like I was a bead in a bead curtain (laughter), like I was a molecule in outer space, and everyone else was, you know, molecules of the same size. We were all just molecules together. I couldn't tell which molecule was me and which was someone else. And I had this really clear revelation that all of our emotions are just molecules. You know, there are molecules in our brains. We are molecules. Our emotions are molecules. It's so funny that we take them so seriously. Like, why do we take ourselves so seriously? And so sure enough, you know, by the end of the session, I really did feel less afraid. And I felt like my emotions were sort of less acute. And I felt like I was ready to really be on my own.

GROSS: Did that feeling last?

WILLIAMS: Yes. It really did. I can't say that, you know, there's no backsliding. I mean, there are certainly days where, you know, I may feel a little bit lonely or a little bit afraid. But for the most part, I - that really turned a corner for me.

GROSS: So you think that the psychedelics, really, were helpful?

WILLIAMS: For me, they were really helpful. I would be very reluctant to advise someone, you know, to follow my path through heartbreak. I think everyone's path has to be their own. There are a lot of people for whom psychedelics aren't going to work. For example, if you're on antidepressants, apparently, they don't work. You want to make sure that you have a lot of support when you do something like this. You want to make sure you find someone who's really trustworthy. There are risks involved for sure with taking these substances.

GROSS: Do you think that your ex-husband has experienced the kind of emotional and physical upset that you experienced after the divorce?

WILLIAMS: No, not at all. And that's so irritating, you know? I talked to Helen Fisher...

(LAUGHTER)

WILLIAMS: I talked to Helen Fisher about this. And I was like, it's such a pain in the neck, you know, all the things you're telling me to do - tell my own story, you know? I was like, what happens to the person who does the leaving? What happens to the dumper? Does he just skate away, you know? Is he just relieved to be done with you and ready to move on and never looking back? And she said, you know, really, we don't know. We haven't studied the dumpers, you know, as much as we've studied the dumpees. Certainly, I think there is a lot of emotional upset also, you know, involved with splitting up your family. And there's probably a lot of guilt. My ex-husband actually read a draft of my book pretty early on. I didn't want him to be surprised by it. And I wanted to give him an opportunity to make some changes. And it was only after he read it that he said, wow, you know, I really didn't know how hard this was for you. And I'm really sorry.

GROSS: What was it like to hear that?

WILLIAMS: It was really nice. It was really nice to hear it. You know, I was kind of - part of me was like, well, what do you mean you didn't know? Like, I did make it clear that this was really hard for me and was not my first choice. But, you know, I think in these kinds of life decisions like divorces, people hear what they want to hear, and they hear truths that are convenient to their decision. But I was really glad that he was able to sort of, you know, look through the effects on his own life of me publishing this book enough to say, you know, I am really sorry you went through all this. And I'm embarrassed and I'm ashamed by my behavior. I really - I wish I had done this better, and I wish I had done it differently. And that was really nice to hear. And I actually - I do forgive him.

GROSS: I want to ask you about being alone. It's something that you've learned to do. How did being alone at the beginning compare to being alone - and I don't mean just being alone in the world, but living alone and not always having a partner there and not always having your children there because you were co-parenting - ditto with the dog. Even the dog wasn't there half the time. And you hadn't lived alone before. You had to learn to do it when you were around 50. So tell us about how that experience changed over time.

WILLIAMS: At first, it felt like I was floating through space upside down, untethered. I was like, where is my grounding? You know, where is my center of gravity? Like, could it exist without other people around me? And again, I think that's kind of a - it's a physical response that your nervous system has when it feels threatened. But, you know, we are very adaptable people. And I did adapt to it, to the point where I - well, when my kids left, you know, I really missed them on the weeks that I didn't have them. But something else happened, which was like, wow, I actually have all this free time, which is something that, you know, working mothers, I think, you know, don't get a lot of. I was like, what am I going to do with all this free time? Well, I might as well do some things I really like. You know, I'm going to spend some more time reading. I'm going to spend some more time exercising. Going to hang out with some friends. I'm going to listen to loud music. It was like, hey, this is actually kind of fun. And I'm an introvert anyway. You know, I don't necessarily feel like I need to be around people a lot. And now I love being alone. I love it.

GROSS: You know, I think that in a relationship, it's easy to and necessary to make a lot of compromises so that both people in the couple can agree on how they want to live and, you know, how they want to manage their lives, what they're going to do together, what they're not going to do together, how much time apart they're going to have. I think women tend to compromise more readily and want to reach some kind of, like, equilibrium in the relationship. And if you've never lived alone, you sometimes don't know, what is it that you really want as an individual as opposed to what is it that you've just compromised on to find a comfortable equilibrium between the two of you? Did you experience something like that?

WILLIAMS: Yes, absolutely. And I think - you know, especially because I met him when I was 18. So I was not yet fully baked as a human being. He was four years older. And, yeah, I think I probably was more accommodating. And, you know, happily so. I was like, OK, you know? You know, I like the way he lives his life. I like his likes. You know, happy to take them on, for the most part. But when he left, it was like, oh, now I actually get to realize that some of those things I didn't really like so much. And there are things about me that, you know, we didn't experience together because I was more accommodating to him. So there's this process of self-discovery that is kind of beautiful in a way.

GROSS: Florence Williams, thank you so much for talking with us. And I'm glad you're doing well.

WILLIAMS: Thank you so much. It's been such a pleasure to be here.

GROSS: Florence Williams is the author of the new book "Heartbreak: A Personal And Scientific Journey." After we take a short break, Maureen Corrigan will review Tessa Hadley's new novel, "Free Love," set in London in 1967. It's about a woman who's a wife and mother approaching middle age, who has an affair with a young man. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF JAMES HUNTER SONG, "I'LL WALK AWAY") Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

Bottom Content