Caption

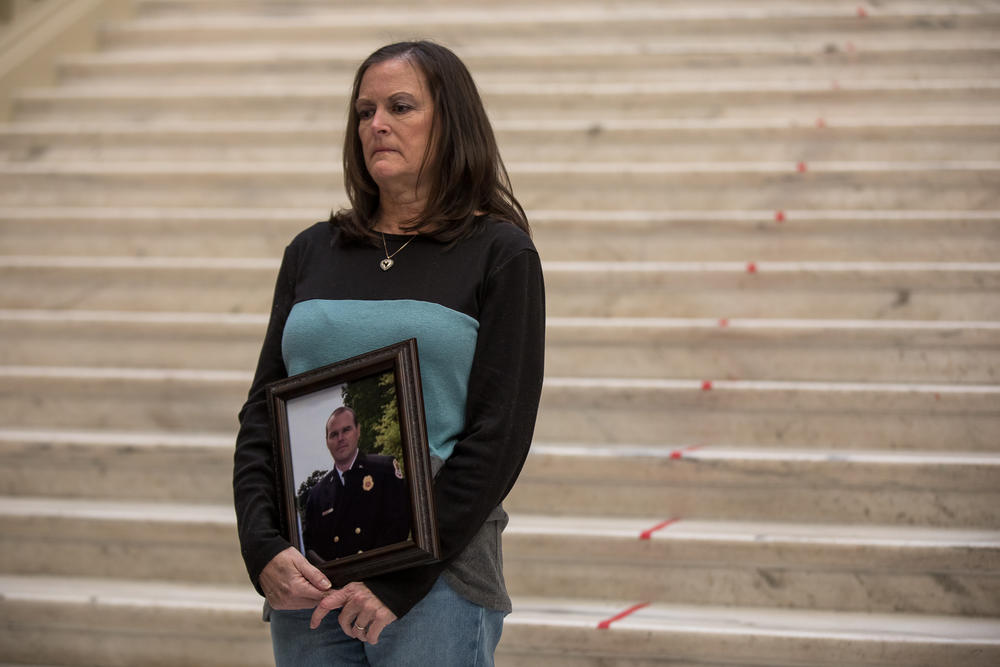

Anita Poole, mother of Gwinnett County Firefighter Chris Baggett, holds his photo on the steps of the State Capitol while advocating for legislation that would create worker's compensation benefits for post-traumatic stress disorder. Baggett died by suicide in 2019.

Credit: Riley Bunch/GPB News