Section Branding

Header Content

Interior Department hires former top cop to review jail deaths on his watch

Primary Content

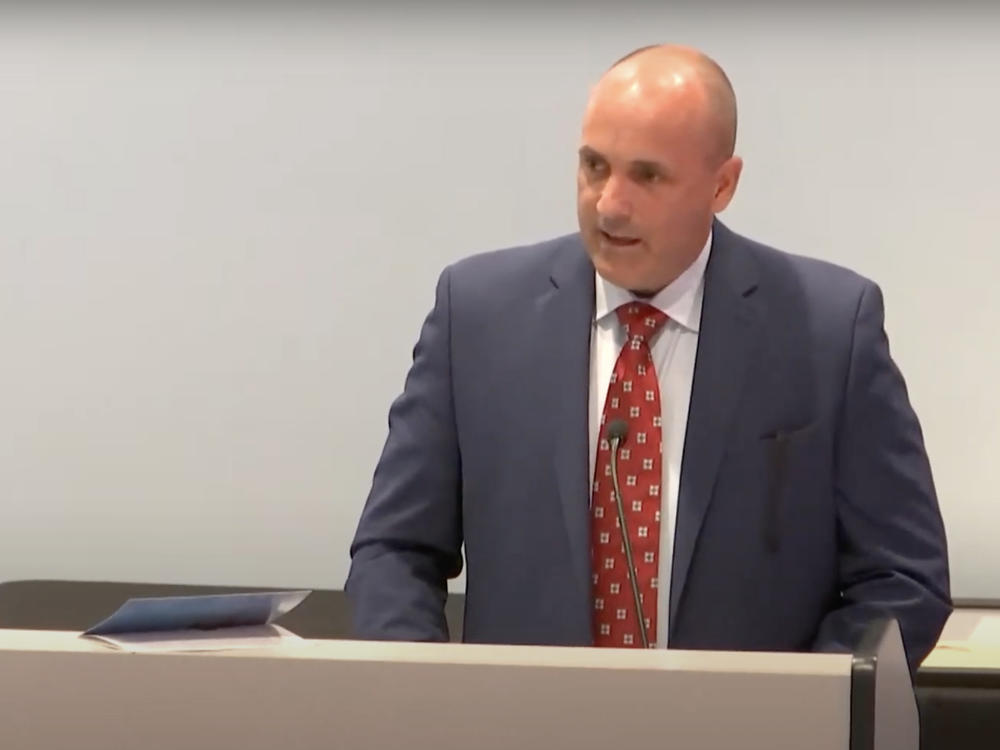

Darren Cruzan was teary-eyed when he delivered his retirement speech to family and colleagues at a gathering in Washington, D.C., last May. He was ending a 26-year career in federal law enforcement — more than half with the Interior Department — and was proud of his tenure as an administrator.

"If I were to go back and rewrite my entire life and career from beginning to now, I might change a few punctuation marks," he said at the time. "But the things that really mattered could have hardly worked out to be better. I really do believe greater things are still to come."

In fact, more was to come.

Less than two months after retiring, Cruzan was back on the federal payroll as a private contractor. He was hired by the very agency for whom he worked to review 16 in-custody deaths at tribal detention centers. At least two of them–and as many as 11 — happened on Cruzan's watch, according to Interior Department records.

"It just seems like a slap in the face," said Chris Yazzie, a former correctional officer whose brother died in 2017 in the Shiprock District Department of Corrections facility in New Mexico. "It's really an insult to the people who died in these jails. This whole situation needs to be reviewed by Congress."

An NPR and Mountain West News Bureau investigation published in June found a pattern of neglect and misconduct that led to inmate deaths at tribal detention centers overseen by the Interior Department's Bureau of Indian Affairs. At least 19 men and women have died since 2016, the review found.

Yazzie's brother, Carlos, died after law enforcement failed to get him immediate medical attention when he was arrested on a bench warrant. His foot was swollen and his blood alcohol content was nearly six times the legal limit. Instead, they put him in a cramped isolation cell and left him unmonitored and unchecked for six hours. A guard handing out inmate jumpsuits the next morning found the 44-year-old day laborer from the Navajo Nation dead.

The investigation also found that correctional officers were poorly trained; one in five had not completed the required basic training, which includes CPR, first aid and suicide prevention. Also, correctional officers at several detention centers often violated federal policy and standards by not checking on inmates regularly or ensuring that they received medical care. And several of the detention centers had been in disrepair for years, with rust in the water, broken pipes and overflowing toilets. At least one jail lacked potable drinking water, forcing jail administrators to turn to charities for bottled drinking water.

Despite repeated requests, Interior Department officials declined to release details of the deaths, including names and the dates the men and women died.

After months of questions and public records requests by NPR and the Mountain West Bureau last year, Interior Department officials announced they would seek an "independent, third-party" review of the detention center program. Four contractors submitted proposals, including two with federal contracting experience, records show. One has completed $15 million in federal contracts since 2008; the other $2.5 million.

Cruzan's company, The Cruzan Group, had no track record at the time. He formed it in December 2020 while he was still working for the federal government, according to Virginia's State Corporation Commission records. His partners include two former Interior Department administrators. It was the company's first federal contract, according to a government contracting database.

Robert Knox, one of the partners in Cruzan's company, and a former Interior Department assistant inspector general, said the company won the $83,000 contract fairly.

"We have done nothing – absolutely nothing – improper," Knox said in an interview.

He said, though, that Cruzan played a prominent role in the company's review of the tribal detention centers. Their role was to evaluate 16 closed in-custody death investigations from 2016 to 2020 and determine exactly what happened in each death; whether the rules were followed; and whether policy changes are needed, according to BIA documents.

Knox said Cruzan's extensive knowledge of Indian Country was essential for the study, which he said was completed in December but hasn't been disclosed publicly. The Cruzan Group and the BIA declined to release a copy to NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau.

"There was a deliberate effort to take a look at these unfortunate losses of life and try and understand what happened and whether there were any changes that could be made to try and prevent anything of the same sort happening in the future," Knox said.

Cruzan was the top law enforcement officer at the BIA and the Interior Department for nearly a decade. He also headed the BIA's Office of Justice Services, overseeing more than 70 tribal detention centers across the country. Cruzan left the Interior Department for the Department of Homeland Security in 2019.

He declined three requests for an interview.

In some cases, former employees are allowed to bid on contracts with the agencies they once worked for. But Virginia Canter, a former associate counsel for ethics for Presidents Obama and Clinton, said awarding the contract to someone who oversaw a troubled program but is now being paid to point out the problems, raises conflict of interest issues.

"This contract just makes no sense," said Canter, who's now chief ethics counsel for Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics In Washington, a nonpartisan government watchdog group. "There are a lot of red flags here that suggest it merits an inspector general investigation."

Federal regulations call for agencies to avoid potential conflicts of interest when working with contractors. That includes contractors who are "unable or potentially unable to render impartial assistance or advice to the Government, or the person's objectivity in performing the contract work is or might be otherwise impaired," according to the regulations.

Scott Amey, a contracting expert and general counsel with the nonpartisan watchdog group Project on Government Oversight, agreed with Canter.

"I have a hard time justifying both the award and how Mr. Cruzan was going to be able to perform on this contract in an objective way due to the fact that he had been in offices that were involved with the BIA's detention centers," Amey said.

Bryan Newland, who was tapped in September to be the assistant secretary for Indian Affairs at the Interior Department, said awarding the contract to Cruzan's company did not violate federal regulations.

"I don't have any particular reason to believe that this contract was awarded outside of the regulatory process," Newland said in an interview.

When asked why he thought it was a good idea for the agency to hire Cruzan's company, Newland deferred to the contract office.

When Cruzan took over as director of the BIA's Office of Justice Services in 2010, he established policies and guidelines for operating the jails. He also oversaw the internal affairs division, which investigated in-custody deaths under his authority. He later moved to the Interior Department but continued to oversee the corrections programs, including the jails. During that time, there was at least one problem that led to the deaths of at least three inmates: the lack of on-site doctors or nurses, law enforcement records show.

In July 2016, after Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), was lobbied by a nonprofit health care organization on the Navajo Nation, he sent a letter to BIA Director Michael S. Black regarding the absence of medical personnel at the jails. Two months later, Black replied saying that Cruzan's office was addressing the issue and encouraged McCain to reach out to him, according to a copy of the letter obtained by NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau.

It's unclear whether the senator's office ever reached out. The issue was never resolved. McCain died of brain cancer in 2018.

Brandy Tomhave, a lawyer and member of the Choctaw Nation who sparked McCain to write the 2016 letter, said she urged Cruzan's office to provide onsite medical care. He failed to do so, she said.

"He was the director of the shop," Tomhave said. "These are conversations and communications that were happening right under his nose. And if he wasn't able to plug in in real time then, then I think that raises questions about his competency to audit the results now."

In 2017, as head of the Interior Department's Office of Law Enforcement and Security, he oversaw policing and corrections for five agencies: the National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Reclamation and the BIA, where he continued having oversight of the jails.

As the Interior Department's top cop, Cruzan's office was responsible for deciding whether any in-custody deaths warranted further scrutiny. If so, Cruzan would chair a group of top agency officials known as a "serious incident review group."

This group would evaluate an in-custody death investigation, vote on whether department policy changes were needed, and produce a report. Interior Department officials said in a letter to the Mountain West News Bureau this week that they could not find any indication that the group had convened during Cruzan's tenure.

Cruzan's prior work with the Interior Department and BIA, and his oversight of the tribal corrections program during much of the span of this study, doesn't concern Knox, a partner with the Cruzan Group.

"I know [Cruzan] had relationships with the BIA," Knox said. "[But] there was never a moment where any consideration was ever voiced — nor would have been tolerated. None of us would ever do anything ... to try and conceal someone's malfeasance or misbehavior."

But it does concern Amey, the government ethics expert.

"This is the perfect example of worst practice when it comes to government contracting," Amey said. "This is the kind of thing that makes people distrust the government and decisions that are being made."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content