Section Branding

Header Content

The first images from NASA's new space telescope show how it's coming into focus

Primary Content

The powerful new James Webb Space Telescope has captured its first starlight, a milestone for the $10 billion space observatory — but it's not yet sending home the kind of breathtaking vistas of the cosmos that astronomers hope to unveil this summer.

That's because the telescope's 18 gold-coated, hexagonal mirror segments aren't yet perfectly aligned and are basically acting like separate telescopes.

When astronomers point the observatory at a bright single star, the mirror segments each capture a different vision of that one celestial object, and the images are all out of focus and distorted.

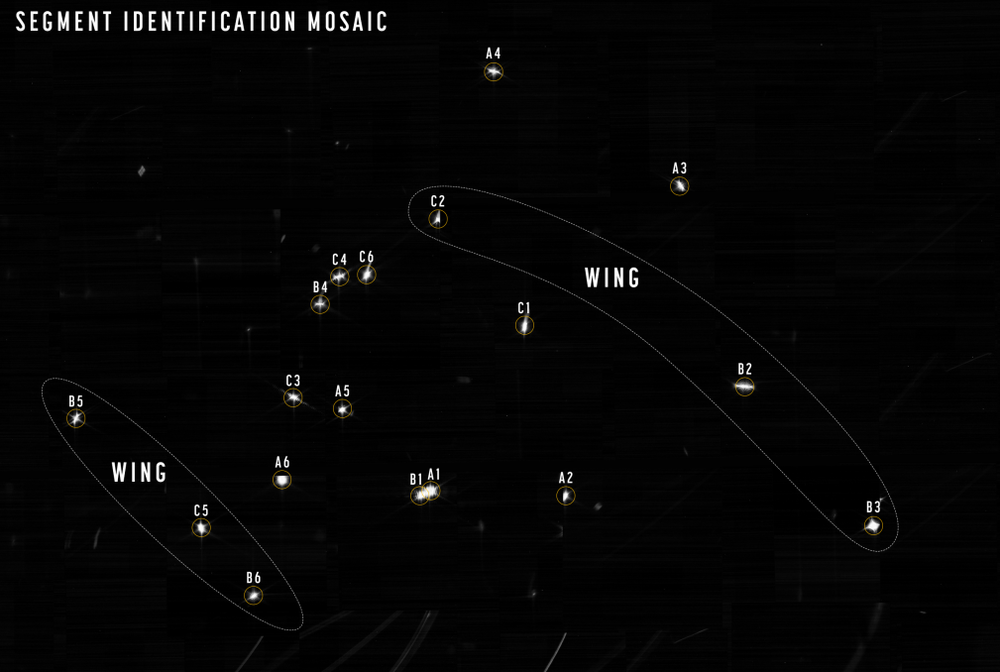

One mosaic released by NASA, for example, looks like just a dark sky speckled with 18 little dots. Each dot is a different view of the same star, and each is labeled with the name of the mirror segment that captured it.

Images like these are incredibly important as mission managers start to carefully adjust the position of each mirror segment to get them working as one giant mirror that's 21 feet across.

"This amazing telescope has not only spread its wings, but it has now opened its eyes," says Lee Feinberg, Webb's optical telescope element manager at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., who adds that all the initial results match their simulations and expectations. "It is still early, but we are very encouraged with what we are seeing."

So far there's no sign of any major flaw, like the one that troubled the Hubble Space Telescope before astronauts went up and fixed it. But Feinberg cautions that there's still plenty of work ahead. He thinks they won't know for sure that everything is OK until some fine-tuning that should occur in March.

The first light came into the telescope's main imager, a near infrared camera called NIRCam, early on the morning on Feb. 2. Scientists gathered at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore to watch and cheer.

"The excitement of finally getting some light through the telescope onto NIRCam's detectors was really hard to express," says Marcia Rieke, principal investigator for NIRCam and regents' professor of astronomy at the University of Arizona in Tucson, who has dedicated about 20 years of her life to this project. "This place was a giant celebration because the light had made it and we were super-duper happy."

The very first images were just a quick engineering check to make sure that nothing was blocking the path of light into the detector. "We got beautiful — at least beautiful to a person who has worked on NIRCam for a long time — images," says Rieke.

"After all these years, to actually see data when we are in zero gravity, in space, it is emotional," says Feinberg. "In the room, when we were looking at the data, people were really excited. But, you know, we still are being a little cautious because we still have things that we have to get through."

Nonetheless, Feinberg recalls that when he went home a few days after seeing those initial images, his wife said it was the first time she had seen him smiling since December. "We're all feeling energized by all this," he says.

The James Webb Space Telescope, which launched on Christmas Day, has been in the works for decades and was so over budget and so delayed that at one point, lawmakers in Congress tried to kill it. The telescope is so big that it had to be folded up to fit inside a rocket and then it unfurled itself out in space. The three-story-tall observatory is now parked in a special orbit around the sun that keeps it about a million miles away from Earth.

Once it is fully operational, this telescope should be able to capture faint infrared light that has been traveling through space for almost the entire history of the universe, revealing what the first galaxies looked like after the Big Bang. It will also allow astronomers to probe the composition of the atmospheres of planets that orbit other stars, searching for combinations of gases that might indicate the possible presence of life.

Marshall Perrin, Webb deputy telescope scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, says that the mirrors' separate depictions of a single star showed up pretty close together in images taken with the camera, suggesting that the mirrors are already aligned reasonably well.

"It's a real testament to the care and the precision with which the observatory was put together on the ground and with how smoothly the ride to space went and all those deployments," says Perrin. "And that has put us in a great starting position to begin aligning these mirrors to act as one."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.