Caption

The proposed Spaceport Camden site has a long industrial history. Much of the manufacturing took place before state and federal agencies regulated hazardous waste.

Credit: Spaceport Camden

The proposed Spaceport Camden site has a long industrial history. Much of the manufacturing took place before state and federal agencies regulated hazardous waste.

Mary Landers, The Current

Ricky Manning loved working at Union Carbide in the 1980s.

“That was my favorite job in my whole life. Really, Union Carbide, Rhone-Poulenc, Bayer they were all are great companies to work for,” said Manning, 60, listing the companies that manufactured munitions and pesticides on a marsh-front property where Camden County is poised to build a spaceport. “They just took care of their people.”

But precisely because he worked there he’s adamant the county should not buy the land from its present owners, Union Carbide and Bayer Crop Science. A special election on March 8 will ask Camden voters if they want to repeal the county’s option to purchase the first of these properties. Manning sits firmly in the “vote yes” category.

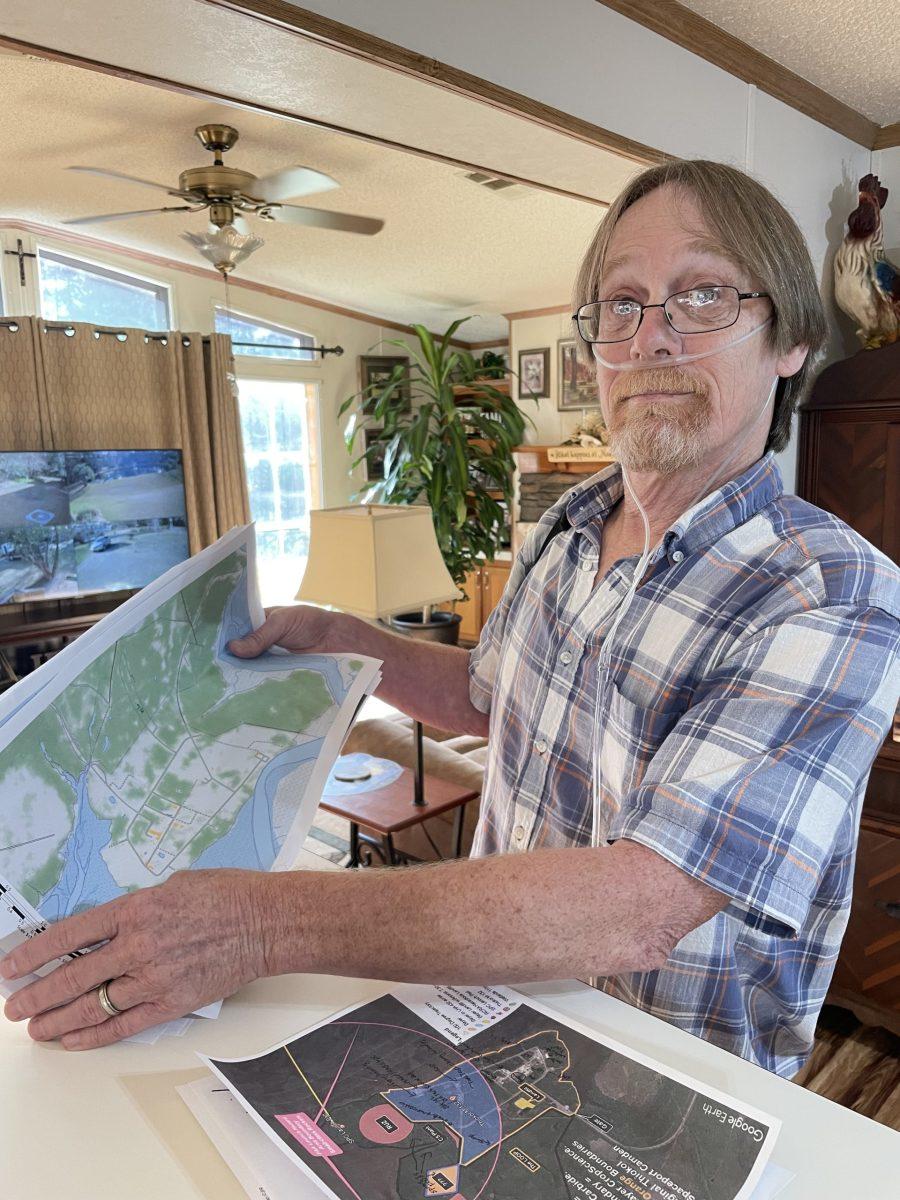

Ricky Manning looks over maps of the Union Carbide site, where he once worked.

“I know what’s out here,” said Manning, who requires supplemental oxygen to treat his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and “popcorn lung,” conditions he attributes at least in part to breathing in nitric acid, sulfuric fumes, acetic acid fumes and dust at the site. “I don’t want my tax dollars, I don’t want my kids, my grandkids having to pay for all this stuff. This place is a mess.”

Lots of spaceport opponents agree with him. Like Jim Goodman, one of the two named plaintiffs who filed the petition triggering the referendum.

“The first guy that gets on a bulldozer and drops the blade into the earth and trips over unexploded munitions and scatters whatever is buried beneath there, that’s a potential lawsuit right there, Goodman said. “It’s a wasteland.”

County officials and and some environmental consultants contend the risk to the county is manageable.

Manning grew up hunting and fishing on the site, where his dad also worked. About a year out of Camden County High School, Manning himself got a job at Union Carbide and trained with others for about 18 months before helping to set up a plant that produced the herbicide Amiben, used to kill weeds in soybean fields.

He worked there about 12 years and can still rattle off the chemical names and processes they employed making the herbicide, ending with “so you decarboxylated and then you went to 12,000 psi hydrogenation reaction and added hydrogen right on it and you come up with Amiben.”

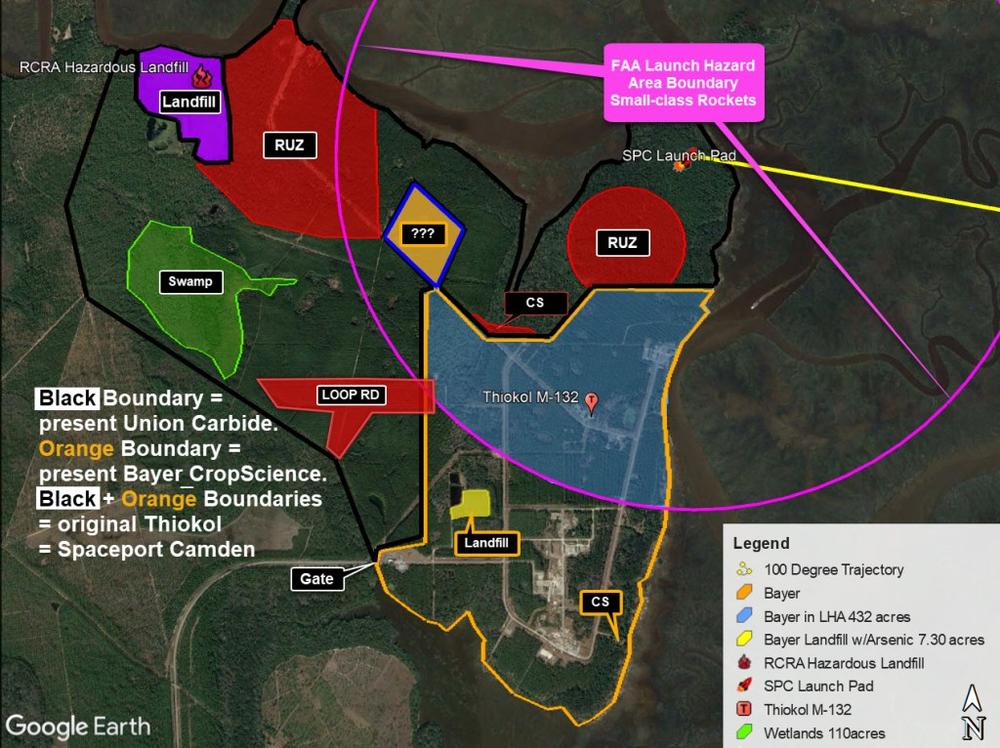

Viewing a map of the Union Carbide property and the adjoining acreage now owned by Bayer Crop Science, Manning traced with his finger the routes they’d take to cart away waste.

“Right here that was that wastewater plant put into service for the Amiben plant,” he said, pointing to the southeastern tip of the Bayer property. “And we’d pipe it down here. We used to haul sludge that came out off the filter press down here, down the road — boogedy, boogedy, boogedy — all the way out to this landfill,” he said, noting that the wet sludge dripped onto the road that whole three-quarter mile stretch.

Even if the landfill is carved out of the deal and retained by Union Carbide, as planned, Manning fears the possibility of other, undocumented pollution. And while much of the land where he remembers spills and lax safety protocols is now owned by Bayer and not part of the planned purchase from Union Carbide, it’s still part of the proposed launch site as described by the Federal Aviation Administration.

The spaceport site, about 11 miles east of Woodbine, was settled as the homestead by a Revolutionary War soldier, Charles Floyd. Floyd’s family developed it as Bellevue Plantation. Evidence of the tabby plantation home remained on the site, a 2014 report Union Carbide commissioned from environmental consultants CH2MHill states.

The tabby remains of the Bellevue Plantation house shown in a 2014 report by CH2MHill for Union Carbide.

From 1927 to 1942, the site was part of a tract known as the Sea Island Game Preserve at Cabin Bluff. Then in the 1940s a forest products company used it as a tree farm. Then its industrial stage began.

“In 1962, Morton Thiokol Corporation purchased the property for producing and testing solid rocket motors for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the report states. “The site was chosen because of low-cost shipping access to the then Kennedy Space Center in Florida.”

Camden County officials point to this history as evidence of Camden’s roots in the space industry.

But Morton Thiokol Corporation later used the site for producing specialty chemicals and ordnance items. A tragic explosion and fire at that Thiokol plant in 1971 claimed the lives of 29 workers, many of them Black women who had been recruited to work there producing trip flares for use in Vietnam.

Union Carbide purchased the 7,193-acre property in 1976 and produced pesticides there until 1986. Late that year Union Carbide sold the manufacturing plant and some of the adjacent land to Rhone-Poulenc, which eventually became Bayer CropScience. Industrial activities on the site ended around 2007. Bayer CropScience closed and demolished the manufacturing facility in 2012. Union Carbide retained ownership of the approximately 4,012-acre site.

As Manning points out, much of this industrial history took place before state and federal agencies regulated hazardous waste.

An area identified as Big Cypress Pond sits in the south central part of the Union Carbide site.

“There weren’t no regulations back in them days,” he said. “So that’s what I’m saying. There’s no telling what else they’re gonna find out here. That’s why they need to leave this place alone.”

“With its coastal setting, diverse habitats and cultural features, and proximity to high quality lands such as Cumberland Island, the site represents an exceptional opportunity for conservation and enhancement in rapidly developing southeast Georgia,” the report states.

The CH2MHill report concludes it’s a prime area to preserve.

The Federal Aviation Administration issued Camden a site operators license for Spaceport Camden in December, making it the 13th spaceport licensed in the US. The county spent more than six years and over $10 million to get to this point. The license allows up to 12 small rocket launches per year, for an unprecedented flight path over homes located downrange on Cumberland and Little Cumberland islands.

But each launch will require separate and more rigorous safety analysis than did the site operators license. (The environmental analysis of Spaceport Camden evaluated safety based on a hypothetical small rocket whose specifications don’t match any rocket yet developed.) And before any rocket’s safety can be analyzed, Camden must purchase, lease or obtain a site use agreement for both the Union Carbide and Bayer properties.

“The proposed launch site would be constructed within an existing 11,800-acre industrial site, consisting of property currently owned by the Union Carbide Corporation and Bayer CropScience,” the December Record of Decision from the FAA states.

Camden officials are quiet about the Bayer site and the pollution there. If there’s an agreement with Bayer, it hasn’t been made public.

The final Environmental Impact Statement says, “According to Camden County, purchase of the Bayer CropScience property is not speculative.” Bayer isn’t saying much either. David Pittman, listed as a Bayer point of contact in a 2020 application for a launch operator’s site license, declined to comment.

The EIS offers a brief response to almost 30 public comments expressing concerns about the Bayer property, including concerns that “access to the Bayer CropScience property apparently has been so restrictive that it has not been evaluated with the rigor done on the Union Carbide tract.”

“According to the County, the site investigation of the Bayer site conducted in connection with the County’s prospective purchase of the property indicates that the locations of the existing and proposed infrastructure are not likely to be contaminated. Environmental review under NEPA by FAA will be required for any proposed modifications to the Launch Site Operator license or any future Launch License application,” the final EIS states.

Annotated map of Union Carbide and Bayer properties created by Steve Weinkle

Steve Weinkle, a Camden resident who runs a website Spaceportfacts.org critical of the effort, said more attention is needed on the Bayer site.

“Keep in mind that about 470 acres of the Bayer property needed for the launch hazard zone has not been involved in any Environmental Impact Statement work,” he wrote in a recent email.

The Union Carbide site is another matter. The county has had an option to buy the chemical company’s 4,000 acres since 2015 and have extended the contract several times. Camden officials say they intend to acquire the land but not the risk.

“To ensure the health and safety of all involved in this project, Camden County and (Union Carbide) have extensively studied the environmental conditions on the property,” Camden spokesman John Simpson wrote in an email. “While the County will continue to retain trained experts to follow recognized Department of Defense, Environmental Protection Agency, and state regulatory standards and guidelines while conducting any necessary intrusive activities on the property post-closing, (Union Carbide) will remain responsible for addressing many of the remaining issues to the satisfaction of Georgia EPD.”

The 4,000-acre Union Carbide site contains a 58-acre hazardous waste landfill and buffer containing 2.8 million pounds of aldicarb, the active ingredient in the pesticide Temik; 37,500 pounds of acetone and methyl chloride, both solvents; and empty boxes and bags containing aldicarb residue. The landfill and a buffer would be carved out from the portion sold to Camden for the spaceport, but an environmental covenant on the site places restrictions on the entire site, not just the landfill. Among other provisions, the covenant prohibits any residential uses or use of groundwater for drinking.

That landfill is permitted under the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, a law is meant to provide for the proper management of hazardous and non-hazardous solid waste. RCRA (pronounced reck-rah), is administered in Georgia by the state Environmental Protection Division.

“Union Carbide Corp. will continue to own and maintain the landfill and buffer area post-closing, still subject to the RCRA permit, and will continue to be responsible to address any remaining concerns that Ga. EPD may have elsewhere on the site,” Simpson wrote.

Camden County Administrator Steve Howard

At a January hearing related to the upcoming March 8 referendum, County Administrator Steve Howard testified that the county knows what it’s getting into with the Union Carbide property.

“We felt very confident on what was on that property as well as brownfield programs,” Howard said. “And also Gerald Pouncey was brought on our team; he’s (worked on) the world’s largest redevelopment, brownfield program in the United States, the Atlantic Station, and we felt very confident after his review.”

Pouncey is a senior partner and head of the Environmental, Infrastructure and Land Use Practice at Morris, Manning & Martin in Atlanta and served as environmental counsel to Jacoby Development in their conversion of a old steel mill site into 138-acre residential and business complex called Atlantic Station. Camden County paid Pouncey’s firm about $6,000 in 2016, budget records indicate. Pouncey did not reply to an emailed request for comment.

Nor did Union Carbide respond to a request for comment.

The county also put together an Environmental Issues Subcommittee of the Spaceport Camden Steering Committee. Led by Camden resident Clay Montague, an ecologist and assistant professor emeritus at the University of Florida, the subcommittee included major stakeholders from the environmental community including representatives from the Georgia Conservancy, The Nature Conservancy and One Hundred Miles.

Montague said that many of the committee’s concerns about leakage from the landfill were alleviated when the county decided to change its license request to be able to launch small rather than medium-sized rockets, moved the launch pad farther from the landfill and dropped the plan for rockets to return to the site.

“It’s smaller rockets, so less noise, less vibration, less things that can be of special interest to that particular landfill. So I think that was a huge concern, that more or less got, I think, probably dissipated to some degree,” he said in a phone interview.

But other concerns may have gained prominence.

“One of the things out there is the contaminated land and how that’s going to be dealt with,” he said. “Personally, I think it will be dealt with adequately, more than likely.”

In its Record of Decision, the FAA indicates the county will be responsible for making sure that it knows what’s on site.

“Once the land is acquired by the County, the potentially contaminated sites could continue to be managed under the existing hazardous waste facility permit, or it is possible that another State program, such as the Georgia Brownfields Program, could be utilized. Also the County, as the owner of the property, would be responsible for any limitations placed on the property as part of State-approved corrective actions for the historical sites,” the Record of Decision states.

Additionally, the FAA’s EIS makes it clear that environmental conditions would have to be documented before the county buys the site.

“(T)he land acquisition process (due diligence) would require completion of a Phase I Environmental Site Assessment to document environmental conditions at the Spaceport Camden site. Based on the Phase I results, additional investigations may be initiated to better characterize areas where potential contamination may be present.”

Montague expects the county will partner with a commercial space company to make its analysis and mitigation more affordable. But the county doesn’t have a contract with one yet.

For Manning, who worked there years ago, it’s too much of a risk.

“Why does my county want to buy this place with our tax dollars when it is probably one of the most contaminated places in the country? I know it’s probably the most contaminated in Georgia,” he said. “I know what’s in that dirt. I put some of it in there.”