Section Branding

Header Content

With a nod to 'Lolita,' 'Vladímír' makes a sly statement about sex and power

Primary Content

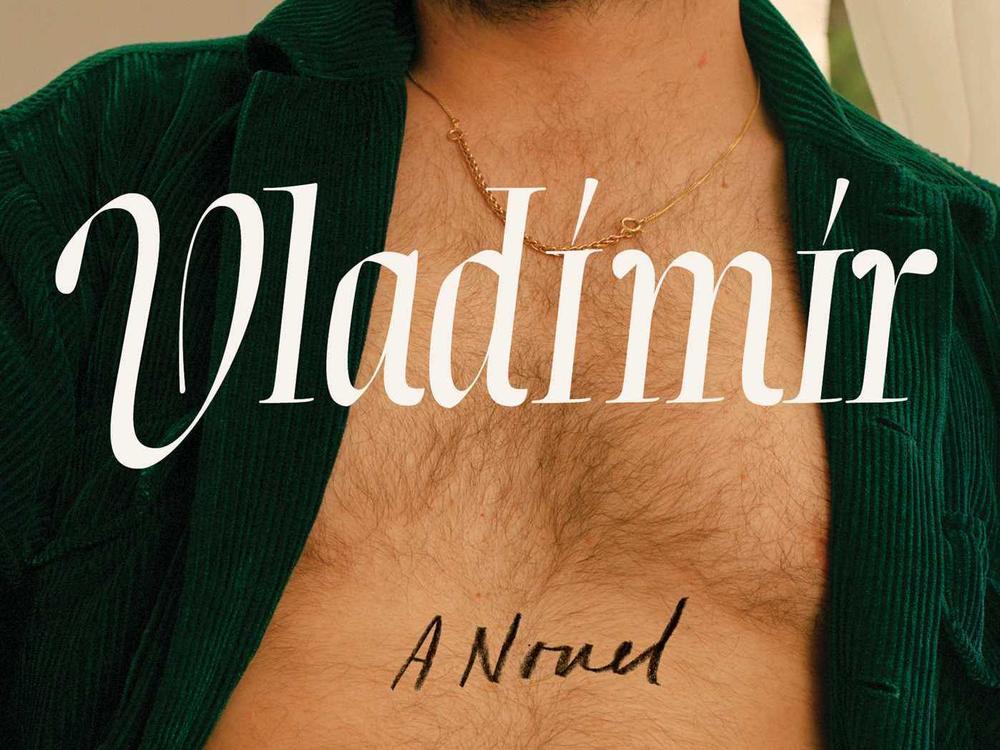

The guilty pleasures of Vladímír, a virtuoso debut novel by Julia May Jonas, begin with its cover: a close up from the neck down of man's very nice open-shirted chest and hands resting on his clothed crotch. That naughty cover, combined with the novel's title, also serves as a warning that this is going to be a sly and subversive read. After all, there's only one Vladimir who reigns supreme in the literary realm, so any novel that gestures to Vladimir Nabokov and, by implication, Lolita is a novel to be wary of.

Our unnamed narrator here, our Humbert Humbertina, if you will, is a professor of women's literature in her late 50s who's so witty, sharp and seductive that, as a reader, I was pretty much putty in her hands, as generations of her students have been.

When the novel opens, however, our narrator finds her status and feminist credentials jeopardized because of her husband's decades of bad behavior. John is the chair of the English Department at their small liberal arts college and he's a seasoned philanderer. The couple has always had an open marriage, so our narrator was vaguely aware of these so-called affairs with students.

But sexual politics on campus have changed over the years, most dramatically with the advent of #MeToo. A petition, signed by over 300 students, is calling for John's removal. Whispers are growing louder that our narrator herself should resign because she was an "enabler."

Here's our narrator's dismissive initial take on the situation:

At one point we would have called these affairs consensual, for they were. ... Now, however, young women have apparently lost all agency in romantic entanglements. Now my husband was abusing his power, never mind that power is the reason they desired him in the first place. ...

As to the age of the women, I felt too connected to my experience of myself when I was in college to protest. When I was in college, the lust I felt for my professors was overwhelming. It did not matter if they were men or women, attractive or unattractive, brilliant or average, I desired them deeply. I desired them because I thought they had the power to tell me about myself.

You may recoil from our narrator's cool rationale — her discounting of her husband's taking advantage of generations of young women — but surely you can also hear how deft she is in her professorial way of complicating the situation, prodding us readers to look at things from another angle.

What also complicates the situation is Vladimir, a newly hired assistant professor who arrives on campus with his emotionally fragile wife, a writer, and their small child.

Vladimir is a gorgeous flirt, given, as our narrator says, to "sensual display(s) of his corporeal beauty"; at one point he stands in our narrator's office doorway and "lift[s] his left hand over his head, ... stretching his body, like a nymph at a fountain."

As a post-menopausal woman of substance, our narrator long ago turned off the pilot light of her own lust; now Vladimir has re-ignited it. Confessing that "[v]anity has always been my poorest quality," she commits herself to a regimen of early morning boot camps at the local Y, whitens her teeth, massages her cellulite, and attempts to, as she says, "erect a fortress of care and grooming" around her body — all the while hating herself for doing so; for worrying that Vladimir may be repulsed by, say, the appearance of her upper arm: its "flesh hanging like a ziplock bag half-filled with pudding."

I should have mentioned at the outset that Vladímír, the novel, opens with a Prologue in which our narrator describes Vladimir, the man, unconscious and shackled to a chair, a prisoner of our narrator's outsized erotic fantasies. But that bizarre image might have pre-emptively closed your mind to the allure of this extraordinary novel, which is so smart and droll about the absurdities and mortifications of aging and sexual shame, as well as the shifting power dynamics on college campuses.

Above all, amidst this terrible current wave of book banning and idea policing, Jonas's debut raises the question — as Lolita itself always has — of how we determine the "value" of literature. We can seek to suppress that which upsets our sense of morality or we can engage with what is disturbing, offensive, deeply wrong. And, when reading the artful Vladímír, we can also have a damn good time doing it, too.

Copyright 2022 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.

Bottom Content