Section Branding

Header Content

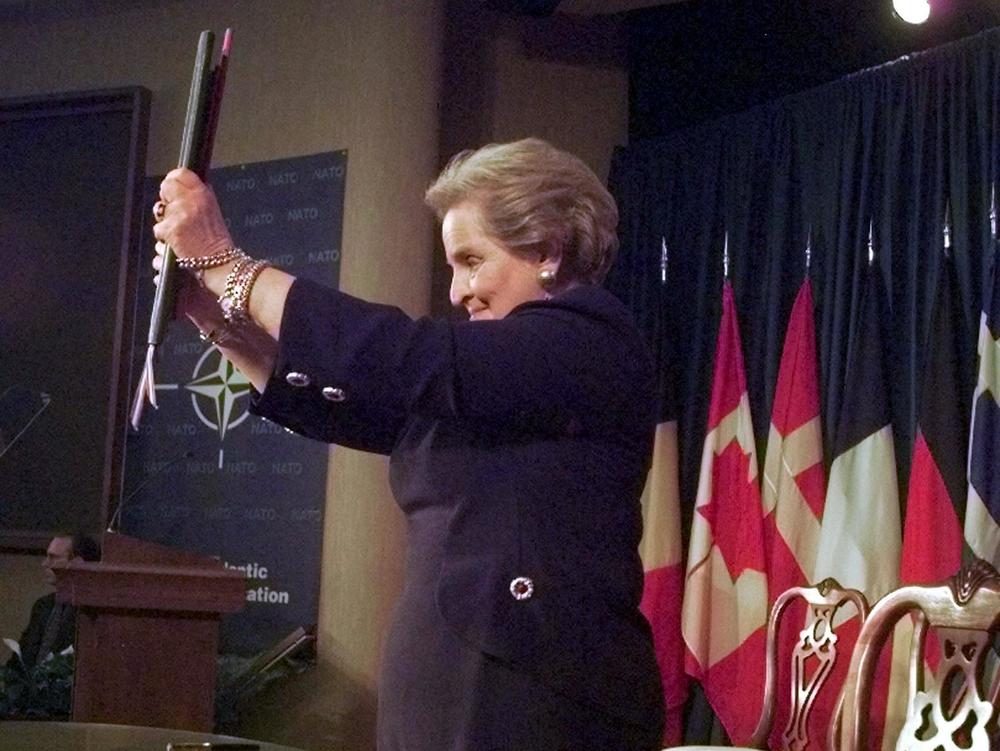

Madeleine Albright kept up her trailblazing work long after being secretary of state

Primary Content

Madeleine Albright, a refugee brought to U.S. shores after fleeing Nazis and communists and who went on to become the first woman to serve as secretary of state, died on Wednesday of cancer. She was 84 years old.

Albright had a long and storied career in foreign policy, serving as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations from 1993-97 before reaching the pinnacle of diplomacy: secretary of state. She was the first woman to hold the position and the highest-ranking woman in government at the time.

"Madeleine was always a force for goodness, grace, and decency—and for freedom," said President Biden in a statement after her death.

When Albright left office in 2001, she vowed she wasn't finished.

"I am still here and have much more I intend to do," she said. "As difficult as it might seem, I want every stage of my life to be more exciting than the last."

From refugee to U.N. ambassador

For Albright, diplomacy was in her blood.

Born Marie Korbel in 1937 in what was then Czechoslovakia, her father was a member of the Czechoslovak Foreign Service and later served as ambassador to Yugoslavia. Twice her family was driven to leave their home — first during Nazi occupation and again for good when communists seized power.

At 11 years old, Albright arrived at Ellis Island.

She studied at Wellesley College, marrying Joseph Albright three days after graduation.

She raised three daughters while earning a doctoral degree from Columbia University.

Albright then went to Capitol Hill, working as a legislative assistant to Sen. Edmund Muskie, the Maine Democrat who served as President Jimmy Carter's secretary of state, before becoming a counselor to Carter and serving on the National Security Council.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton appointed Albright ambassador to the U.N.

"At this time of turmoil and hope, this assignment is a major challenge," Albright said in her confirmation hearing.

Her tenure prompted a shift in the way women diplomats were viewed at the U.N.

"One male diplomat came to her complaining one day and said, 'You know, I watch you and you spend all this time with those women diplomats, when can I have the kind of time that you give to some of these women?' " recalled former U.S. Ambassador for global women's issues Melanne Verveer, who worked for first lady Hillary Clinton at the time. "Madeleine said to him, 'When your government names a woman to head the delegation, I will spend considerable time with her as well.' "

Albright proved adept at making complicated foreign policy accessible to the public.

As part of her campaign to educate civilians on the dangers of landmines, her deputy, Ambassador Karl "Rick" Inderfurth, worked with DC Comics to warn children.

"That became educational comic books with Superman and Batman, and at Madeline's suggestion, true story, Wonder Woman," Inderfurth said. "She said, 'Where's Wonder Woman?' So they did a Wonder Woman comic book as well. It was translated and got distributed to almost all of the landmine-affected countries."

One of Albright's more famous quips came after Cuban military pilots shot down civilian aircraft, boasting that it took a certain kind of fortitude.

"Frankly, this is not cojones, this is cowardice," Albright told reporters, a phrase Clinton called one of the most effective one-liners of his administration's foreign policy.

"She had an enormous gift of being able to explain complex topics in ways that people can understand what it means to their day-to-day lives," said Wendy Sherman, who was a counselor to Albright in the 1990s and is now U.S. deputy secretary of state.

"Women often are afraid of the use of power, she was not," Sherman chuckled. "She was happy to wield it in her own way."

That included using jewelry as a diplomatic tool.

"This all started when ... Saddam Hussein called me a serpent," Albright told NPR in 2009. "I had this wonderful antique snake pin and so when we were dealing with Iraq, I wore the snake pin."

She called the practice one of her most effective, albeit unusual, strategies.

"I became known for using a pin or a brooch to send a message — a butterfly, if I was in a good mood, a balloon to show that I had high hopes, and a spider if I wanted my counterpart to watch out," she said in 2017.

As ambassador, she had a rocky relationship with U.N. Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, whom she criticized for not doing enough to stop the genocide in Rwanda.

Albright later wrote in her memoir that her deepest regret in public service was the failure of the United States to intervene.

"I wish that I had pushed for a large humanitarian intervention," she said in a PBS documentary. "People would have thought I was crazy. It would never have happened, but I would have felt better about my own role in this."

Albright sought an increased role for the U.S. in the U.N. and pressed for aggressive action in Bosnia.

Albright's tenure, however, wasn't without controversy. In 1996, 60 Minutes' Leslie Stahl asked Albright if "the price" of sanctions against Iraq was worth the humanitarian cost, noting the death toll of children.

"I think this is a very hard choice, but we think the price is worth it," Albright answered.

She later wrote that she immediately regretted her words, calling them a "terrible mistake."

"Hope my heels can fill your shoes"

In 1996, Clinton tapped Albright to be his next secretary of state.

"It says something about our country, and about our new secretary of state-designate, that a young girl raised in the shadow of Nazi aggression in Czechoslovakia can rise to the highest diplomatic office in America," he said.

Albright, at 4 feet 10 inches tall, stood out in her cherry suit and pearls in the all-male group. She thanked her predecessor, Warren Christopher, adding, "I can only hope that my heels can fill your shoes."

Clinton, who had said he wanted his Cabinet to look like America, was peppered with questions about whether Albright merited the job.

"I'm very proud to have had the opportunity to appoint the first woman secretary of state in the history of America," Clinton said. "But it had nothing to do with her getting the job."

Verveer recalls Albright calling Jesse Helms, the conservative senator from North Carolina.

"Clearly they didn't see eye to eye on a whole lot of things, and yet she called him and she told him that she had just been nominated and she hoped he would be supportive and that she could work with him," she said. "It was an indication of her ability to be political."

The Senate went on to unanimously confirm Albright.

Not long after, Albright, who was raised Catholic, was faced with a personal revelation: Her parents, then deceased, had converted from Judaism (unbeknownst to her) and three of her grandparents had died in the Holocaust.

The emotional news was met with political cynicism and antisemitism, with pundits questioning what the news meant in terms of Albright's credibility.

Albright recalled the pressure years later.

"I had been asked to represent my country in a marathon, the first time a woman ever had been, and given a very heavy package to unwrap as I ran," she told CSPAN.

A new age

As secretary of state, Albright promoted the eastward expansion of NATO and the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons.

Sherman also credited Albright with making the State Department a more inclusive place, noting she was the first to put Ramadan on the department's calendar.

"She turned to me as a counselor and said, 'Could you organize the State Department to talk about Islam?' " Sherman said. "For many years, talking about religion was something you weren't supposed to do, but obviously, it was a force in the world, and one we had to better understand."

As chief diplomat in the late '90s, Albright pushed for military intervention in confronting the deadly targeting of ethnic Albanians in Kosovo.

Time magazine dubbed it 'Madeleine's War'; airstrikes in 1999 eventually led to the withdrawal of Serbian forces.

Albright also helped to bring Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic into NATO, a crowning diplomatic achievement.

At home, Albright enjoyed attending naturalization ceremonies.

"I heard this man saying all of a sudden, 'Can you believe it, I'm a refugee and I just got my naturalization certificate from the secretary of state,' " she described during a speech at Westminster College in 2019. "So I went up to him and I said, 'Can you believe that a refugee is secretary of state?' "

After government service, Albright founded a consulting firm in D.C.

She returned to the White House in 2012, when President Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor.

Albright stayed active in politics, supporting Hillary Clinton's unsuccessful presidential campaign in 2016.

"Just remember, there's a special place in hell for women that don't help each other," she said at one rally to cheers.

She took some flack for that, especially from supporters of Clinton's primary rival, Sen. Bernie Sanders. It was a phrase she had used countless times, but still, Albright apologized for turning it political.

Inspiring the next generation

Albright remained an active professor at Georgetown University, training the next generation of diplomats.

"She took the time after each class each week to have brown bag lunches with the students and to hear their stories, which is unusual for someone at her level," said Sophia Meulenberg, who was Albright's teaching assistant.

"The lessons about hard work and perseverance and truly loving the craft are ones that she exemplified every day and I can't state enough how important that was for me," said Meulenberg, who is now a Foreign Service officer.

In her lifetime, Albright saw two more women become secretary of state: Hillary Clinton and Condoleezza Rice.

She reflected in a 2012 CSPAN interview that what was once considered groundbreaking achievement was no longer a rarity.

"My youngest granddaughter, when she turned 7, said to her mother, 'So what's the big deal about Grandma Maddie being secretary of state? Only girls are secretary of state.' "

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content