Section Branding

Header Content

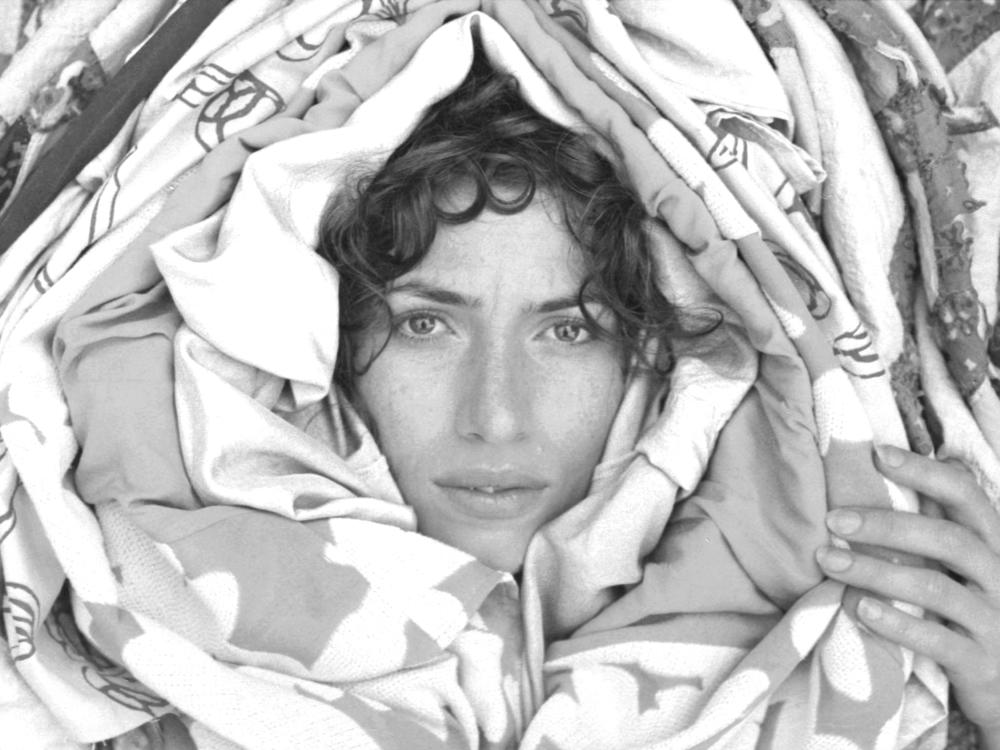

The Masked Singer

Primary Content

An interviewer asks Aldous Harding if she thinks her music is vulnerable. "Totally," she replies. "It's vulnerable in the sense that it can be rewound, fast-forwarded, stopped or deleted, not bought, criticized." When a journalist asks about vulnerability in art, usually the question is aimed at whether the artist feels disproportionately known. Does the music open a way into a private place that has now been amplified? Are the particularities of your life story suddenly out there for anyone to consume? Harding speaks to a different kind of vulnerability, not emotional but economic: The New Zealand artist makes records, and people could always decline to stream or purchase them, or tell each other to avoid what she's made.

This type of redirection, from typical question to atypical answer, threads much of her music. Across her past three albums — 2019's Designer, 2017's Party and her 2014 debut — Harding has eased from severe, guitar-based etchings into arch, sleight-of-hand chamber pop. She sings over instruments that, for the most part, engage with the human body directly, whose tones reverberate in actual space, far from the black box of synthesized sound. And yet, nearly everything else about her music cuts against the expectations this setting creates. Harding never sits us down to tell a story about something that has happened in her life, nor does she sketch out fictions in recognizable beats. Pop's usual terms of exchange, in which an identifiable "I" and "you" want things from each other, and negotiate via melodies that push them toward resolution or deeper conflict, are consistently sidelined.

On this year's Warm Chris, the vacancy she leaves by avoiding those conventions has its own gravity. Throughout the album (released March 25), her elastic singing voice stretches across scenes you can't quite see but can powerfully feel. There are people in there, though their movements are obscured; you're invited to listen in on their intimate exchanges, even if you're not sure who's who. To follow Harding into this uncanny world is to feel both held and adrift: safe in the company of a skilled navigator who won't tell you where we're going, or how she aims to take us there, or how close to the waterfall she plans on steering the boat.

Acoustic instruments prime us to believe we are about to hear the truth. Listen to an Aldous Harding song and you can piece together the objects that made each sound, envision the physical mechanics that activated them: A musician empties their lungs into a saxophone; another depresses the keys of a piano, which trigger tiny hammers to vibrate taut strings. You might fairly expect, then, to hear a continuous voice cutting through the mix, a single narrator guiding the way. Harding slips that trap. As each track on Warm Chris begins, she invokes a new character, with a slant in her voice. As soon as the song is done, she discards it and becomes someone else.

On "Fever," she sinks down into her lower register over a piano-snare one-two punch, savoring the creases that spider over her notes. For "Lawn," where bass notes pop like bubbles and the drums take on an aerated shuffle, she drifts up an octave into a whispery head voice, like she's telling a secret. Occasionally, she converses with herself. "Tick Tock" sees her toggling between two characters — one cool, composed and knowing, the other enthralled and giddy — sometimes within the space of a sentence.

These oscillations derail a longstanding habit across popular music — the impulse to hear voice, especially a woman's, as a malleable substance onto which experience imprints, passively documenting a real self. In her 2019 book The Race of Sound, Nina Sun Eidsheim tracks the tendency of critics and historians to hear Billie Holiday's idiosyncratic vocal style as the direct result of her early life trauma. When listeners do this, Eidsheim writes, "the artist's skill is reduced to an expression of biographical circumstances." The idea of the sung voice as essence, something that inevitably tumbles out of a singer following feelings she can't fully control, shuts a performer's agency out of the frame. If Holiday is only venting story, the necessary implication is that she is not really writing it.

Certain timbres Harding uses set her in a lineage of other idiosyncratic performers. Joanna Newsom and Regina Spektor surface as audible predecessors here, women using acoustic compositions as bedrock for the outgrowth of challenging vocal streaks. Both their voices are so stylized that they strain the critical impulse to hear voice as autobiographical record, and throughout the 2000s and 2010s, music writers lobbed questioning, diminishing language in response. A 2009 review of a Spektor concert rendered her music as "kooky urban sea shanties full of breathy babble and exaggerated glottal stops." In a 2015 essay for The Awl, Leah Finnegan collected the responses of male music critics to Newsom's voice, quoting phrases like "goofy young-girl singsong," "brave little coo" and "dying cat."

This language disparagingly orbits the phenomenon known as "indie girl voice" or "singing in cursive," a much-parodied vocal mode that crimps and elongates the vowels, and seemingly calls back to a simpler time before we were all on the computer. It's the voice whose jitteriness escapes the flattening algorithms of Auto-Tune, a newer and more frightening technology when Spektor and Newsom got their start, and gestures instead toward some elusive primordial authenticity. If Auto-Tuned voices were explicitly "fake," these tugs to a pre-digital sociality careened too far, for some listeners, to the other end of the spectrum — too outrageous to be explained by autobiographical imprint, and thus calculated, affected, made up.

Like Kate Bush before them, Newsom and Spektor do not often write confessionally. They prefer to catapult their voices along storytelling at the scale of myth, singing with the swing of history. Bush is as likely to be Catherine from Wuthering Heights or Wilhelm Reich's terrified son as she is to sing as herself. Spektor enters the biblical story of Samson and Delilah to extract a feeling of cold and delicate intimacy. Newsom sings about love not as any particular tie between her and a second person, but as the activating force behind all activity on earth. Their voices make characters, and by embodying characters, they are freer to sing beyond themselves. "I think songwriters are more related to fiction writers," Spektor told NPR in 2006. "Who the hell wants to be themselves all the time? It's so boring."

In 2020, Harding shared a similar sentiment. "Do you feel that you're able to be fully yourself, to be honest, in your music?" asked Cheryl Waters on KEXP. "No! It's impossible to tell the truth and be honest," said Harding. "It's a version of the truth. I have good intentions. But it's certainly not the whole. I don't think anyone's ever able to give the absolute truth. I've never seen it, anyway."

Try to pin the lyrics on Warm Chris to clear, perceivable stories and you'll come up empty. Instead, Harding offers a variety of tethers between unnamed and unfixable characters. There might be a passing mention of a spouse or a friend or an exciting stranger. Maybe the song's speaker and her companion are in a defined place, like a hotel lobby or the botanic gardens in Wellington; maybe their only container is the electric charge between them.

Her context-collapsed music opens and envelops the ear, inviting it to make sense of the vacuum — and the ear finds that there is little sense to make, only intermittent pulses of warmth. On her album's title track, she sounds much older than she is: "Oh, Crystal / I got the love for you now / Not that you need it, eh, girl?" she sings with a wink on her voice. She reads almost grandmotherly, secure in her unnecessary love, radiating it without fear of its rejection or hope of its return. The "I" and the "you" never settle into recognizable roles; Harding only hints at their possibilities with twists of voice and careful pacing, nudging you to lean a little closer than you might for songs that paint their drama on the surface.

If Holiday's voice conferred a sense of authenticity, and Spektor and Newsom's strained it, Harding's voices do away with the question altogether. Her songs are not opportunities to know her, not portals to a rarified inner world, but a series of meeting places. They are stages where she can ask: Who are we if not what we are to each other? And doesn't that mean we're always in flux?

Her music videos, confounding as the songs themselves, carry these questions as well. She is a skillful screen actor who understands the power of small movements, how a pinch of the facial muscles or an understated dance move can be more compelling than the format's typical flash-bang. When she appears on camera, she tends to fix the viewer in an unflinching gaze. It can feel confrontational almost to the point of awkwardness, as if you were suddenly the one being seen.

But Harding takes the awkward moment as threshold, and moves past it into a subtle, welcoming space. The video for Designer's "The Barrel" presents an infinitely unfurling gallery of minuscule gestures that transforms at the end into unselfconscious full-body play. The video for the non-album track "Old Peel" stages a typical bar performance, but swaps Harding for her frequent collaborator Martin Sagadin at the mic. While the rest of the band dutifully and politely performs with an approachable amount of feeling, Sagadin dances exaggeratedly, only occasionally remembering to lip-sync to the vocal track. In the closing shots, Sagadin walks through a tunnel while Harding hitches a ride on their back, the singer and her avatar both ejecting themselves from the performance expected from them, heading somewhere else.

Harding's art challenges the habits people use to relate to each other. Stories about who a person really is, those ones that are supposed to be recorded and relayed in an authentic voice, fall away here, irrelevant, as the artist asks us to drop our scripts and plunge into the unsheltered moment. It can look frightening from the outside, this place with no scaffold, but on the inside it's just a site of play — a chance to make it up on the spot in generous collaboration with whoever else is in there, to lose the constraints of individuation and spark something new.

Warm Chris abounds with invitations to that place. The album confronts and disarms. It's funny in that way, as in comic, as in: Absent rules, you can't help but laugh — not at the music, but at what it's melted around you, what you thought you couldn't put down but now feel freer without. You see someone moving in a way you thought wasn't allowed, hear her vocalizing in ways that don't track with what voice is supposed to do, and suddenly you're included in the permission she's granted herself. Suddenly, in your own body, you share her smiling ease.

Sasha Geffen is the author of the book Glitter Up the Dark and host of the podcast Shattering Gleam.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.