Section Branding

Header Content

Researchers explore an unlikely treatment for cognitive disorders: video games

Primary Content

Updated April 15, 2022 at 10:33 AM ET

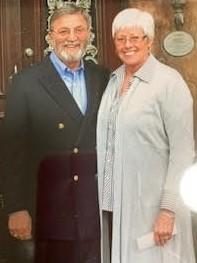

The neurologist said Pam Stevens' cognitive impairment couldn't be treated. After suffering a stroke in 2014, the 79-year-old wasn't responding to medication. She and her husband, Pete Stevens, were told to give up hope.

"On two separate occasions, over a two-year period, the neurologist said there was nothing we could do," said Pete Stevens. "He said 'just take her home and be prepared that she's gonna die.'"

But he refused to accept that grim prognosis. He was willing to try anything — including an experimental video game therapy — to restore Pam's brain.

Combating cognitive decline

After a referral from her psychiatrist, the Stevenses finally made it to Sarah Shizuko Morimoto and her lab at the University of Utah. Morimoto's work focuses on cognitive disorders, especially those related to aging brains such as geriatric depression and mental decline.

"My interest has always been in the intersection between mood and cognition, so how you think affects how you feel," said Morimoto. "I started thinking 'could we enhance the functioning of brain circuits through our eyes instead of our ears?'"

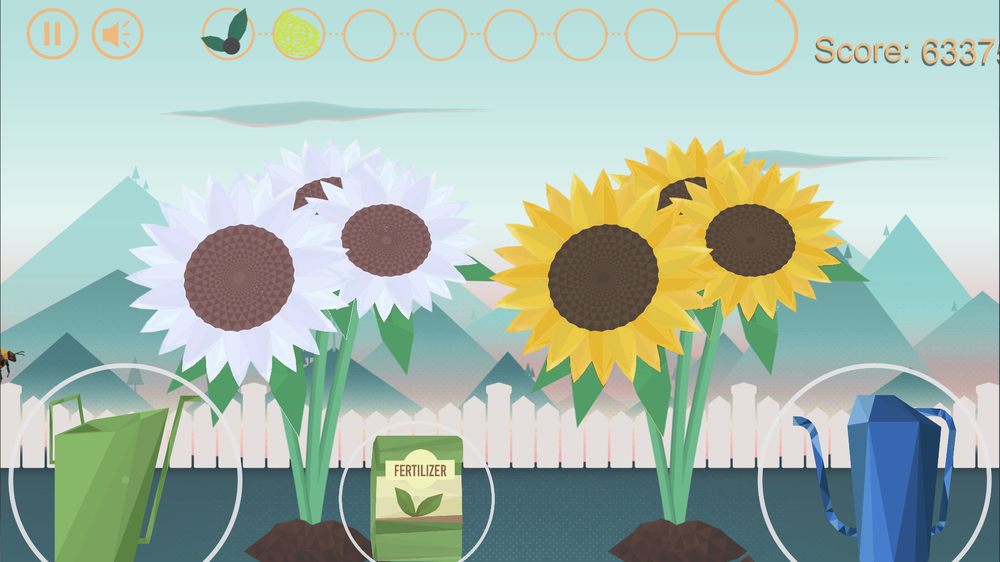

Enter Neurogrow: Morimoto's gardening video game is designed to target and enhance the functioning of neural circuitry. Their hope is that an aging brain, when exposed to the program, would eventually respond better to medication like anti-depressants.

Video games distract, amuse, and inspire. But Morimoto's research asks the question: Can they heal?

More like exercise than play

Neurogrow isn't a blockbuster video game like Call of Duty or Animal Crossing. It has a rudimentary design that eschews cutting-edge graphics and elaborate storytelling for tasks that challenge an aging brain's memory or reaction time. Someone playing Neurogrow might be presented with a specific color flower and be challenged to water it with the correct watering can before time runs out. For a brain unaffected by cognitive impairment, this task would most likely prove easy, but the memorization and timing can be demanding for patients like Pam Stevens.

"When you want a certain part of the brain activated," says Morimoto, "you use something similar to problems in a game. When someone solves a problem, a certain part of the brain lights up. So we started there and gamified those tasks."

According to Morimoto, her team's games aren't supposed to hook you. In fact, Neurogrow isn't much fun at all.

"My games are designed to do something completely different to your brain," she said. "They are not designed so that you want to keep playing or spend more money on it. The things we are asking patients to do are pretty hard and pretty boring, which is exactly the thing that's so hard for them."

It's more exercise regimen than play. When Pete Stevens would drive Pam home after her Neurogrow sessions, he noticed how much it exhausted her.

"There were times when we would not be even a mile away from Morimoto's office, and she'd be asleep in the car," he said. "Other times, she'd make it home but then sleep for four hours. It was an emotional and physical drain."

But Pam's hard work paid off. After completing several sessions over four months, Pete and her doctors noticed positive changes in Pam's behavior; She was more social, more conversational, and Pete even mentioned that Pam was reading a book on dialectical behavior therapy before our interview call.

Other researchers thought Morimoto was out of her mind. Video games as a treatment for depression? Unheard of, especially in the elderly, whose brains have gone through normal deterioration as a part of aging.

"Very few people thought this would work," said Morimoto. "They said that there was no way I was going to be able to make a game and get older patients to play it."

But the federal government thought otherwise. Morimoto and her team received a $7.5 million grant from the National Mental Health Institute to conduct clinical trials for Neurogrow.

A private company gets in the game

Neurogrow isn't the only game that claims to treat brain health. EndeavorRx is a video game designed to treat ADHD in children. It looks like a cross between the popular app Subway Surfers and Mario Kart. Developed by Akili Interactive, in 2020 the FDA allowed it to be marketed as a treatment for inattention in kids with ADHD.

While the FDA's blessing seems like the ultimate stamp of approval for a medical device, some researchers are skeptical. Speaking to The Washington Post, Russell Barkley, a clinical psychologist and researcher, called the game a "marketing ploy."

"The effects [of the game] just don't generalize," Barkley said. "You get better at playing the game and anything similar to playing the game."

Rather than improve, for instance, a student's test scores or reading comprehension, these critics say a child using EndeavorRx would only get better at playing games similar to it like the aforementioned Subway Surfers or Temple Run.

But Eddie Martucci, CEO of Akili Interactive, says he can point to tangible results.

"I think the reason there is skepticism, and there's a good reason for it, is that people have been burned by marketing gimmicks, especially in digital health and neuroscience," said Martucci.

"Over time, skepticism has dramatically decreased as we continue to research and show data."

It's not easy deciphering whether or not games like Neurogrow or EndeavorRx work or have long-term benefits. Researchers aren't always keen to divulge their findings, especially if it would reveal game mechanics that could be copied. But without outside verification, it's hard to tell if so-called medical video games have merit.

"We don't get to see the research surrounding it," said Anthony Bean, a clinical psychologist and video game researcher. "Sometimes the data looks muddled when we can see it, but we're also really in the dark with a convenient sample that they have created to verify their game."

But Neurogrow patients like Pam Stevens aren't waiting on independent researchers to give the thumbs up. Neither are investors — Akili Interactive went public and merged with Social Capital Suvretta Holdings Corp., injecting the EndeavorRx developer with about $412 million in gross proceeds.

Keller Gordon is a columnist for Join The Game. Find him on Twitter: @kelbot_

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.