Section Branding

Header Content

As Georgia fentanyl overdoses spike, bill to ease access to life-saving test awaits Kemp OK

Primary Content

Georgians are suffering through a surge in fentanyl overdoses as the synthetic opioid finds its way into more illicit substances across the state.

“We’re packing out clean syringes and taking the dirty ones. We’re also distributing naloxone (a drug that can reverse the effects of opioid overdoses) and training people how to use it. We’re covering pretty much all the bases from a harm reduction perspective, probably keeping pace with Atlanta,” said Christian Frazier, executive director of Focus on Recovery Augusta. “That being said, we instituted this program, A, because it was necessary, B, because it helps us keep our finger on the pulse of the still-using opioid community, and it’s bad.”

Fentanyl-related overdose deaths have spiked since the start of the pandemic, rising more than 106% between May 2020 and April 2021, according to the Georgia Department of Public Health.

The department has also reported at least 66 emergency department visits statewide involving drugs laced with fentanyl between February and mid-March. In some cases, patients were brought in under what was assumed to be a stimulant overdose, but they responded when given naloxone. Cocaine, methamphetamine and counterfeit pills are the most common, but other laced drugs including cannabis products have also resulted in emergency department visits, DPH said.

“It seems like there’s just fentanyl in nearly everything,” said Mona Bennett, co-founder of Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition. “This past summer, there were quite a few overdose deaths because of fentanyl-laced cocaine, fentanyl-laced stimulants.

“We had some naloxone distribution events at Little Five Points, East Atlanta Village, some other places, and in the past, I had to beg stimulant users to please, take some Narcan (a brand of naloxone), but now that fentanyl is so common in stimulants, it’s an easier sell.”

Manufacturers mix fentanyl into their drugs to increase potency and lower costs, but when users don’t know their supply has fentanyl, the dose they are accustomed to can be deadly.

There are test strips available that can quickly determine whether a substance contains fentanyl, but they are in a legal gray area — you can buy them online from places including Amazon, but a police officer could consider them a drug-related object.

A bill on Gov. Brian Kemp’s desk seeks to remove strips that test for fentanyl from the list of drug paraphernalia to help make them more accessible. The governor has until May 14 to sign or veto the bill, or to take no action and allow it to become law.

Atlanta Democratic state Sen. Jen Jordan, who introduced the idea, said she has been hearing from constituents who have lost loved ones to drugs laced with fentanyl. She compared the idea with steps the state has already taken to reduce the harm of opioid overdoses like providing naloxone and passing a shield law that protects people who call 911 to report an overdose.

“It’s one of those things where it’s hard to acknowledge that people are taking these drugs, right? That’s not great,” she said. “But at the same time, we’ve got such a problem that if we don’t acknowledge it and try to do something to mitigate the harm, we’re going to lose so many more people.”

The change to the testing strip policy took a strange path to passage — it was attached to a bill designed to legalize raw milk sales.

Jordan said she had nearly given up on her test strip plan when she noticed the section of state law addressing adulterated food products like milk also addressed adulterated drugs, so she felt amending it to include the test strip language would stand up to objection.

The bill’s Republican sponsors in both chambers agreed, and it passed the Senate 42-10 and the House 110-55.

Effective, but pricey

The strips work great if you can get your hands on them, Bennett said.

They typically require so small an amount of the substance that users can test using the residue on the container that was holding the drugs, she said.

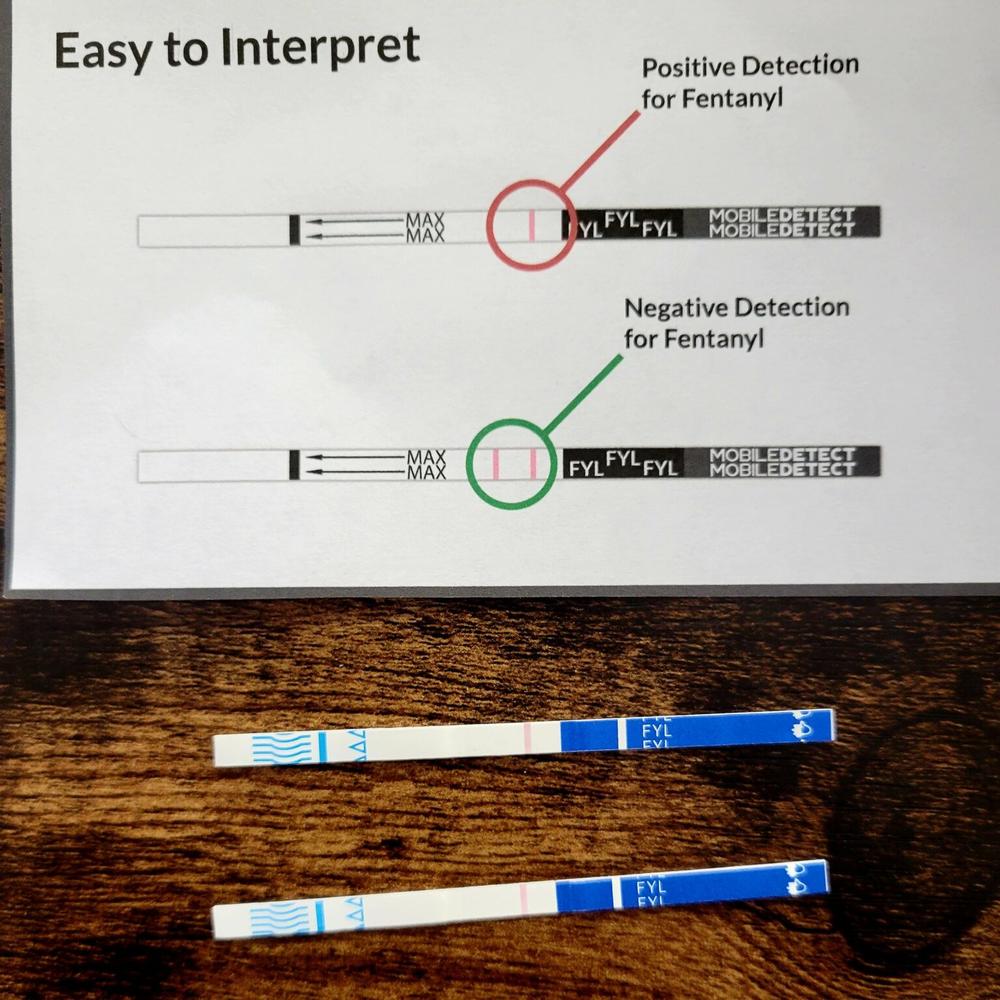

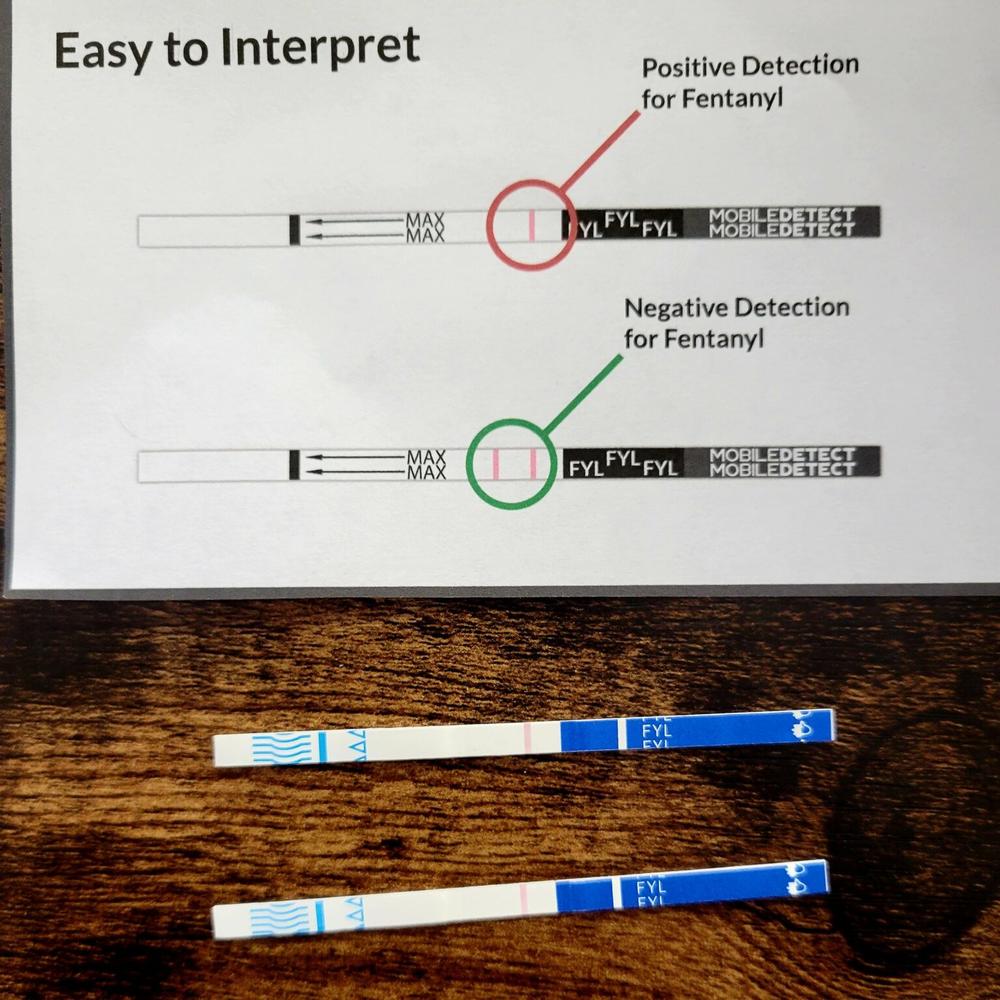

“It takes literally a few seconds to get a result,” Bennett said. “It’s kind of the opposite of a pregnancy test, where one stripe means that there is the presence of fentanyl in the substance test and two stripes is saying that it is not in the substance. And there are always new analogs, but the test strip does detect many of them.”

Bennett tells users to reduce their dose if their supply shows the presence of fentanyl. No matter what the strip says, she tells them to always have a friend nearby with Narcan and gives them a hotline they can call if they have to use alone.

She said Atlanta Harm Reduction’s current supply of test strips is limited and comes from donations, but she’s hoping the rule change will mean more vendors will carry them and the price will drop.

Right now, a box of 100 single-use test strips costs between $125 and $150 on average, she said.

When you are serving a large population of daily users, a buck and a half per strip can add up quickly, especially for a nonprofit, Frazier said.

“We get requests for it every single day. We explain to them every single day why we don’t carry it, because it’s expensive,” he said. “We just tell them, listen, assume that your dope has got fentanyl in it and use accordingly, otherwise, you’re going to be back here tomorrow asking for more Narcan. If the price point was lower, I would absolutely keep more of it in stock because I think that it has a multitude of uses, not only for the active user community, but for family members and allies, spouses. I wish it was cheaper.”

Telling heroin users to expect that their drugs contain fentanyl is not hyperbole, said Riley Kirkpatrick, program director at the Athens-based Access Point of Georgia. A study using spectrometers to analyze substances sold as heroin in Georgia found 100% of samples contained fentanyl, he said.

“There’s literally no such thing as heroin without fent in it anymore down here,” he said. “It is much more likely that people’s heroin has fentanyl in it than it actually has heroin.”

It’s harder to justify allocating resources to test strips for heroin users when a negative test would be a surprise, but the strips can come in handy for people who use other substances, Kirkpatrick said.

“We really just give the fentanyl test strips to folks that are using other things that they’re unsure of, like, especially now with pressed pills, and there’s a lot of pills that people don’t know are pressed,” he said.

Some pills bought from strangers or through social media can be marketed as and formed to look like prescription opioids but actually contain fentanyl.

“Those are the kinds of things where it helps even more, like the fentanyl test strips actually helps them see if there is or isn’t fent in their supply, and with cocaine sometimes,” Kirkpatrick added.

Kirkpatrick said he was heartened by a group of students who came by around New Year’s Eve who were planning on taking ecstasy but wanted to make sure their pills did not contain fentanyl.

“We had college kids show up getting fent test strips, because they were going to roll on E, take ecstasy, MDMA, and that just made me really happy,” he said with a laugh. “Because we were able to supply them, and they were able to test their stuff and make an informed decision as to what they were doing. As harm reductionists, we know that people are going to use no matter what, but we can help them be safe.”

Jordan said she hopes a wider prevalence of test strips will help get the word out among those who are not regular opioid users that fentanyl could find its way into their drug of choice.

“I think what we’re seeing is especially a spike in terms of younger users, recreational, maybe girls’ weekend, whatever it is,” she said. “We’re not even talking about regular users. So, there is an opportunity for education here even talking about these strips.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Georgia Recorder.