Section Branding

Header Content

The Buffalo shooting is a reminder that millions don't live near a grocery store

Primary Content

The racist massacre at a Buffalo, N.Y., grocery store this month has refocused attention on an issue that affects millions of Americans: lack of access to healthy, affordable food.

The shooter not only tore apart lives and families, he also struck an institution at the heart of a community: a grocery store that residents fought for years to get, in a neighborhood that hadn't had a supermarket like it in decades.

"It was the village watering hole," Tommy McClam, a resident of Buffalo's East Side neighborhood, told NPR last week. "It was more than just a Tops grocery store. It was a lot bigger than that for that community."

With the Tops closed for the foreseeable future as authorities continue to investigate the shooting, the community around it has been left without easy access to healthy and affordable food. In other words, it has become a food desert.

What are food deserts? And should we even be calling them that?

A food desert refers to an area where people have limited access to a variety of healthy and affordable food. These areas may have convenience stores, carry-outs, or fast-food restaurants — but they don't have any large grocery stores, supermarkets, or supercenters that carry an array of fresh foods including fruits and vegetables.

In recent years, many of those who work on this issue have been moving away from using the term "food desert."

Caroline Harries, acting director of healthy food access at The Food Trust, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit that works on healthy food access across the country, says calling an area a food desert implies a naturally occurring phenomenon — "rather than a result of systemic practices such as redlining that have caused disinvestment and a subsequent lack of grocery stores in communities."

The term also ignores the many opportunities and resources that exist in these communities, says Harries, who prefers to talk about the "grocery gap" in underserved communities.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is also bypassing the term. The agency's Economic Research Service now uses the terms "low income" and "low access" to designate the areas of the country with limited access to healthy food.

How many people are affected by limited access to healthy food?

An estimated 18.8 million people who live in low-income census tracts also had low access to food stores, according to agency data from 2019, the most recent year available. That's using a measurement that defines low access as living more than 1 mile from a food store in urban areas or more than 10 miles in rural areas.

Low-income census tracts are defined as those with a poverty rate of 20% or higher, or where the area's median family income is less than or equal to 80% of the metropolitan area or statewide median family income, depending on the tract's location.

Such access is a big problem for many Americans. Depending on which measure you use, limited access to a food store affects somewhere between 5% and 17% of the U.S. population, says Alana Rhone, an agricultural economist at the USDA Economic Research Service.

How can I see what areas have low access to groceries?

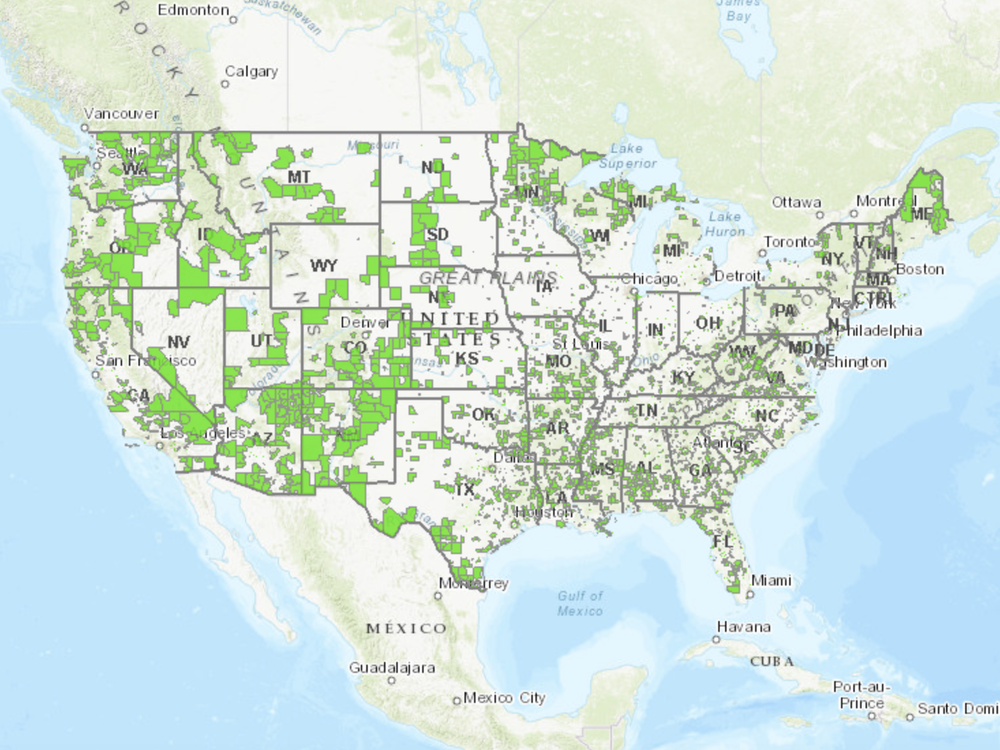

The Food Access Research Atlas, created by the USDA Economic Research Service, provides an overview of food access around the country by showing the census tracts that are low income and/or have low access to a food store.

"Food stores" include supercenters (big-box stores that sell groceries), supermarkets and large grocery stores.

But the USDA map does not necessarily provide a full accounting of people's options.

A 2009 USDA report noted that people do not shop for groceries only near their house: "They travel to work, school, church, and beyond and often purchase food on the way. Using an access measure that only considers distance from home is likely to underestimate the options available for food shopping."

Why does healthy food access matter?

People who live in areas with limited access to healthy and affordable food may be more prone to poor diets and have outcomes such as obesity or diabetes, Rhone says. Food stores also provide community access to government programs that help with food affordability, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

Harries notes that access to a variety of healthy foods is especially important against the backdrop of COVID-19, when health and preexisting conditions like diet-related disease can make people more vulnerable.

It should be noted, however, that the link between food deserts and obesity has been studied many times and is contested.

A 2013 review of the research by The Food Trust and PolicyLink identified several studies that found positive health outcomes were associated with access to healthy food. But the review also highlighted other findings that "question the strength of that connection."

Is the grocery gap getting better or worse?

Progress has been mixed. Between 2015 and 2019, the number of low-income census tracts fell, but the number of low-access areas went up. When combined, the number of communities that were both low income and low access in 2019 was higher than in 2015.

Harries says that in some ways, a lot of progress has been made over the past 10 to 15 years — in terms of awareness and in the number of innovative projects. For example, there are now programs that help corner stores carry fresh produce or make SNAP benefits go further if used at a farmer's market.

But challenges remain, she says, and the pandemic has only underscored how vital a grocery store is to a community.

"We started calling them front-line and essential workers for a reason," Harries says. "They literally became the heartbeat of every neighborhood. And neighborhoods that didn't have a grocery store nearby were all of a sudden in a crisis."

Then there are challenges that go beyond the pandemic: Stores operate on extremely thin profit margins. Independent operators face competition from Amazon and big-box stores. Equipment such as refrigeration has to be maintained.

"We have to keep an eye on every locality across the country to ensure the right supports are in place to keep these grocers viable," says Harries.

How does food access affect rural communities?

Residents of rural areas can be hit especially hard by a lack of grocery stores, especially if they don't have a car, since public transit is rare.

Even for residents who do have a car, the trip to pick up food can be a long one.

"In rural areas, often people have to drive 20, 30 miles to get to a grocery store, which can be an hour round trip. And it's counterintuitive because often rural areas are associated with farmland. But that product isn't always produce that gets back to the local community," says Harries. "This is absolutely an issue that impacts rural areas as well."

How can communities without a grocery store try to get one?

Community members can start by engaging with city and/or county officials to highlight the need and understand what resources might be available to support a project, says Harries.

One resource available in many states, as well as at the federal level, is a public/private program called the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, or HFFI. The program offers financing and technical assistance to support healthy food retailers in low- to moderate-income and underserved communities.

"Operating costs in food deserts are generally higher while profit margins tend to be lower," explains Laura Strange, a spokesperson for the National Grocers Association, which represents independent wholesale and retail grocers. "It sometimes takes a number of years for these stores to become profitable enough to sustain their operations," Strange said in an email.

But HFFIs can help, she says, by "provid[ing] grocers with the initial support they need to help mitigate some of the challenges experienced when operating a store in a food desert."

How much can online delivery services help?

A new study from Brookings found that 90% of people living in low-income, low-access tracts have at least one option for delivery of fresh groceries or prepared foods from among four prominent delivery services: Amazon (Amazon Fresh and Whole Foods), Instacart, Uber Eats and Walmart.

Researchers note that still leaves 4.5 million people in the U.S. who live in low-income, low-access areas outside the reach of these services — mostly in rural areas. Lack of broadband access can also be a barrier.

Harries says grocery delivery apps can be helpful, especially when combined with education and affordability, and she notes that many healthy food financing programs will fund grocery projects that include food delivery components.

But grocery stores provide more than just groceries. They also provide jobs for members of the community.

And their physical presence matters. "People like to go to shop, to see people. To pick out the things they want and touch them," says Harries.

A grocery store is a place, she says, where people go to feel connected to their community.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.