Section Branding

Header Content

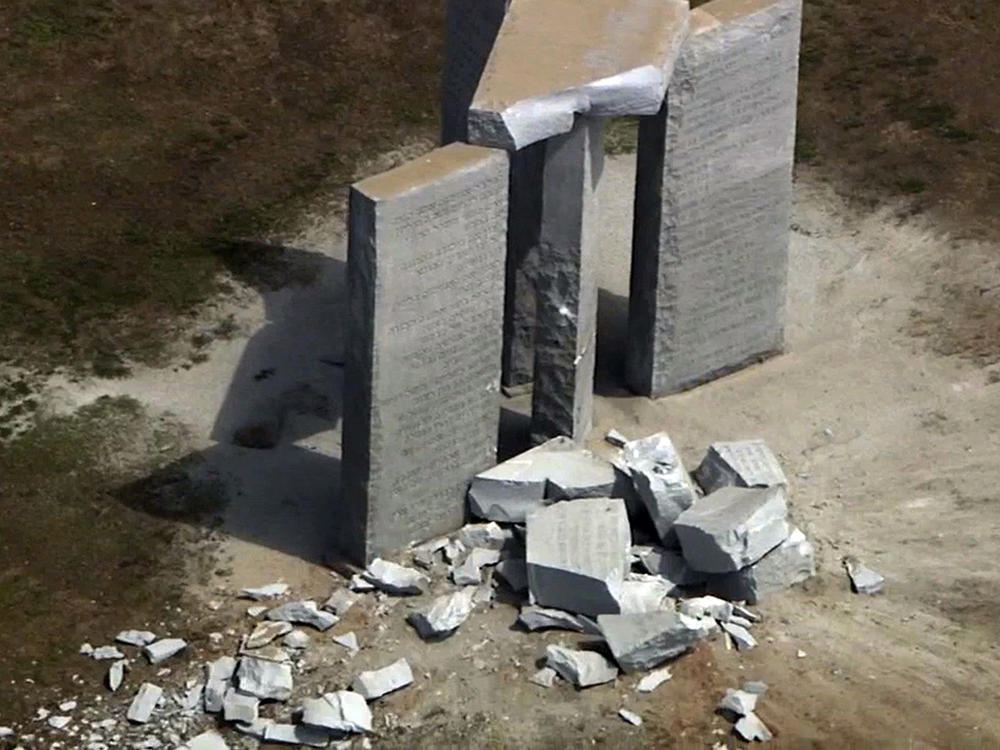

A Georgia monument, seen by some as satanic, was damaged from a predawn explosion

Primary Content

A rural Georgia monument that some conservative Christians criticized as satanic and others dubbed "America's Stonehenge" was demolished Wednesday after a predawn bombing turned one of its four granite panels into rubble.

The Georgia Guidestones monument near Elberton was damaged by an explosive device, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation said, and later knocked down "for safety reasons," leaving a pile of rubble in a picture that investigators published.

Surveillance footage showed a sharp explosion blowing one panel to rubble just after 4 a.m. Investigators also released video of a silver sedan leaving the monument.

After prior vandalism, video cameras connected to the county's emergency dispatch center were stationed at the site, said Elbert Granite Association Executive Vice President Chris Kubas.

The enigmatic roadside attraction was built in 1980 from local granite, commissioned by an unknown person or group under the pseudonym R.C. Christian.

"That's given the guidestones a sort of shroud of mystery around them, because the identity and intent of the individuals who commissioned them is unknown," said Katie McCarthy, who researches conspiracy theories for the Anti-Defamation League. "And so that has helped over the years to fuel a lot of speculation and conspiracy theories about the guidestones' true intent."

The 16-foot-high (5-meter-high) panels bore a 10-part message in eight different languages with guidance for living in an "age of reason." One part called for keeping world population at 500 million or below, while another calls to "guide reproduction wisely — improving fitness and diversity."

It also served as a sundial and astronomical calendar. But it was the panels' mention of eugenics, population control and global government that made them a target of far-right conspiracists.

The monument's notoriety took off with the rise of the internet, Kubas said, until it became a roadside tourist attraction, with thousands visiting each year.

The site received renewed attention during Georgia's May 24 gubernatorial primary when third-place Republican candidate Kandiss Taylor claimed the guidestones are satanic and made demolishing them part of her platform. Comedian John Oliver featured the guidestones and Taylor in a segment in late May. McCarthy said right-wing personalities including Alex Jones had talked about them in previous years, but that "they sort of came back onto the public's radar" because of Taylor.

"God is God all by Himself. He can do ANYTHING He wants to do," Taylor wrote on social media Wednesday. "That includes striking down Satanic Guidestones."

The monument had previously been vandalized, including when it was spray-painted in 2008 and 2014, McCarthy said. She said the bombing is another example of how conspiracy theories "do and can have a real-world impact."

"We've seen this with QAnon and multiple other conspiracy theories, that these ideas can lead somebody to try to take action in furtherance of these beliefs," McCarthy said. "They can attempt to try and target the people and institutions that are at the center of these false beliefs."

Kubas and many other people interpreted the stones as some sort of guide to rebuilding society after an apocalypse.

"It's up to your own interpretation as to how you want to view them," Kubas said.

The site is about 7 miles (11 kilometers) north of Elberton and about 90 miles (145 kilometers) east of Atlanta, near the South Carolina state line. Granite quarrying is a top local industry, employing about 2,000 in the area, Kubas said.

Elbert County sheriff's deputies, Elberton police and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation are among agencies trying to figure out what happened. Bomb squad technicians were called out to look for evidence, and a state highway that runs near the site was closed for a time.

No suspects were identified.

Kubas said local officials and community leaders will have to decide who, if anyone, pays for restoration.

"If you didn't like it, you didn't have to come see it and read it," Kubas said. "But unfortunately, somebody decided they didn't want anyone to read it."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.