Caption

Randy Nichols is the executive director of the nonprofit Redeemed Living.

Credit: Ellen Eldridge / GPB News

Residents in rural South Georgia are adamantly fighting a zoning request — a faith-based nonprofit called Redeemed Living wants to build cabins for men in addiction recovery on 23 acres of local farmland. But the neighbors don’t want them living next door.

The goal, according to Redeemed Living, is to build a sober living community where a group of men will share space and help keep each other accountable as they rebuild their lives from addiction.

Randy Nichols, 56, spent 25 years in and out of drug rehabs before he finally made the commitment to “get clean.” He is now the executive director of Redeemed Living.

“When I came to Redeemed, I really didn't have a place to go that was safe for me to build my life back up, save my money, get remarried and start to live again,” Nichols said. “On top of that, my son gets to come live with me, which is something I had given up on.”

Randy Nichols is the executive director of the nonprofit Redeemed Living.

The value of recovery and recovery-oriented systems of care is widely accepted by states, communities, health care providers, peers, families, researchers and advocates including the U.S. Surgeon General and the National Academy of Medicine.

But recovery from drug and alcohol addiction is tough.

Part of the reason people fighting the disease of addiction relapse, end up in the correctional justice system, or die is that they need a comprehensive recovery plan that is difficult to access without money.

We (could) have ten times more ministries than Redeemed Living in any area of the state of Georgia and other places and it still would be a drop in the bucket because we just can't find them

Treatment costs for substance use disorders are responsible for 10.4% of the global burden of disease, according to a study published in 2016.

Medical detox, inpatient rehabilitation and ongoing counseling are often not covered by insurance, even when patients have coverage. Many substance abuse counselors don't even accept insurance because of the legal loopholes.

And insurance never covers costs of living like food and housing.

RELATED: With few other resources, people with behavioral health issues find treatment in jails and prisons

One of the most important aspects of recovery — finding an affordable, safe place to live with people supportive of a sober environment — is often the most difficult to access.

However, the residents of Lowndes County’s Howell Road, which is where Redeemed Living wants to build, say they do not want an unregulated halfway house in their community.

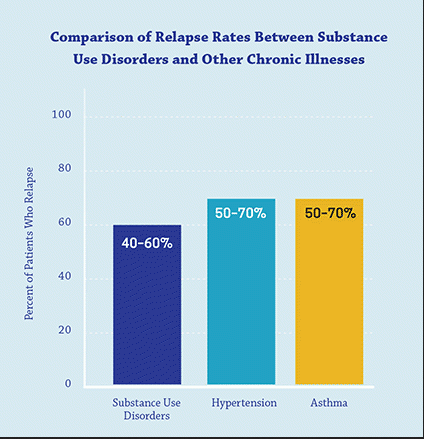

When people in recovery successfully complete a hospital or jail-based detox program, they must be careful choosing where to live. Former friends, environments and activities can make it easy to relapse and start using drugs again — which roughly 40% to 60% of people with addiction do, according to the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Addiction is compared by NIDA to chronic illnesses like hypertension, diabetes and asthma. If people with the disease of addiction stop following their medical treatment plan, they are likely to relapse.

Relapse rates for people treated for substance use disorders are compared with those for people treated for high blood pressure and asthma.

Halfway houses, as they are commonly called, are an important link between treatment and a full return to society.

NIDA estimates Georgia has 256 recovery homes in its 159 counties. The majority are in the metro Atlanta area.

Casey Corbin, a substance abuse counselor and a Redeemed Living board member, said the most frustrating part of his job involves finding a transitional home for people in their first year of recovery after a treatment program.

“We (could) have 10 times more ministries than Redeemed Living in any area of the state of Georgia and other places and it still would be a drop in the bucket because we just can't find them,” he said.

Because transitional housing arrangements are not treatment facilities, they are not regulated, and they are typically not covered by insurance, state Sen. Kay Kirkpatrick said.

And, because it's often a cash business, people can take advantage of the situation that parents and loved ones find themselves in when trying to help, said Kirkpatrick, who sponsored bills to protect syringe exchange programs and to crack down on bad actors in the transitional housing community.

MORE: Georgia’s Plan To Crack Down On Halfway House ‘Cash Cows’

"It was a cash cow for people," explained Missy Owen, who started the Davis Direction Foundation to support people in recovery after her son, Davis, died of a heroin overdose in 2014.

She said the problem is that anyone can open a sober living house without a permit or certification required. Often, a person with as little as two months of sobriety becomes the house manager, Owen said.

"They needed money and they say, 'Hey, I have a house. If I open up my house to five or six people, 10 people, 12 people and put them on the floor on sleeping bags or whatever and charge them all $200 a week, then I'll be sitting pretty and, you know, who cares,'" Owen said.

The Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities offers housing assistance but only to individuals with a diagnosis of a serious, persistent mental illness, and there is a list of additional requirements such as chronic homelessness and a history of incarceration.

Redeemed Living founder Brent Moore said his nonprofit has been helping five men at a time with affordable living accommodations. Morris runs a separate business as his day job and considers Redeemed Living service work.

Morris, 33, said he felt lucky to have a supportive family when he stopped using drugs and alcohol. He believes God led him to open the current sober house his nonprofit runs.

The home, inside the Valdosta city limits, provides five men only their own bedrooms, with access to a shared kitchen and conference room for recovery meetings.

The men have all passed a background check and completed a treatment program, Corbin said.

During the Lowndes County Planning and Zoning Commission meeting, Moore said publicly that many men in recovery had “burned their bridges,” which was then used against him by residents against the Howell Road development.

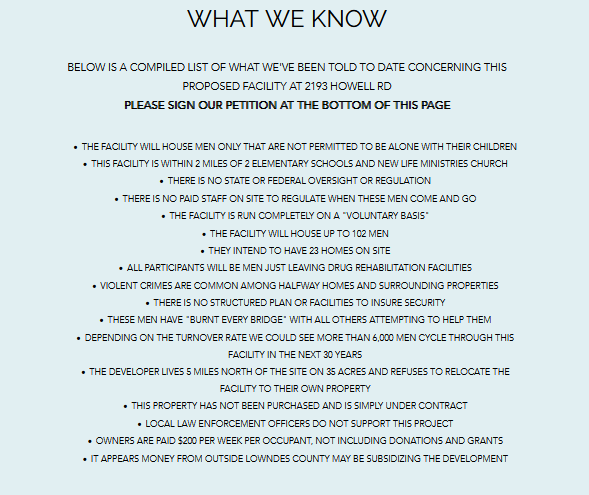

The group of neighbors to the proposed development put up a website and petition.

The website also includes implications that the men who would live on the 23-acre property would be pedophiles.

A screenshot of the website neighbors launched to oppose Redeemed Lving's planned development.

Resident Jesse Bush said he believes Morris and the Redeemed Living board of directors are “good-hearted folks” who want to help addicts, but Bush wants them to stay in a place with government regulation.

“A place with a high police presence, government oversight and that sort of thing,” Bush said. “Not out in the community with a bunch of homes and schools adjacent to the property.”

But taxpayers pick up the tab for state-run facilities, so, more often, nonprofits like Redeemed Living pick up the slack when it comes to transitional housing.

Michael Henderson spoke on behalf of the opposition at the Lowndes County Board of Commissioner's June 16 meeting.

"I'm sorry, but we are not ready to base the security of our family and our children on hope," Henderson said. "That's like putting snakes in the front yard and putting my child on a tricycle and sitting around saying, 'I hope she don't get bit.' This has to be a guarantee. It can't be based on hope alone."

Henderson said the group chose him to represent them because he understands the nature of addiction and recovery. Henderson said he started experimenting with illegal drugs when he was 16 years old, and later served seven years in prison for robbery by force and cocaine possession.

"It all boils down to a choice, no matter how good or how bad a program is," he said. "A real choice has to happen no matter what that is."

That choice is easier made when you have the right support, resources and access to a program of reformation and transformation, he said.

"And that was just the avenue that God had for me," Henderson said.

At the end of his prison sentence, Henderson moved to the state-run Valdosta Transitional Center, which is only available to felons nearing the end of their sentence.

Neighbors opposed to a planned sober living community posted handmade signs near the 23-acre property.

Savannah Baker, another local resident who fiercely opposes Redeemed Living's plan, said she is a mother and a certified police officer.

She said she worries about her family's safety if the community opens to men in addiction recovery.

"With drugs, crime goes hand in hand," Baker said. "It doesn't matter if you're currently doing it. You did do it. It's just like Michael had mentioned. It's always there. You get a taste of it and you're going to go right back to it."

Moore and Corbin both spoke at the meeting about the need for programs to keep men in recovery accountable.

They even agreed with the opposition that more regulation would be a good thing.

"It would be nicer if these kinds of ministries had some type of oversight from the government so that all of these parity issues and the manipulation of the system and all that kind of junk, you know, would be addressed as something illegal," Corbin said. "That would be great."

Corbin noted that Redeemed Living did legally file and obtain a 501(c)3 designation, so the nonprofit is regulated as such.

They also sought out oversight from the Georgia Association of Recovery Residences, which conducted an inspection of the Valdosta home and made sure the men had proper living conditions. GARR also reviewed the transitional housing's program for accountability, which includes voluntarily sharing location with a phone app.

GARR is another nongovernmental group that isn’t accountable to the public, but it is a founding member of the National Alliance for Recovery Residences (NARR) and is one of the oldest recovery residence organizations, founded in 1987 out of the need to evaluate and monitor quality of care in the rapidly growing field of addiction recovery related services in the state of Georgia.

It was the first association to develop and maintain a standards system for recovery residence programs in the state.

The Lowndes County Board of Commissioners Chairman, Bill Slaughter, cast the tie-breaking vote June 16 to approve Moore’s plan.

He said the state needs more transitional housing to get people back on their feet — like Henderson had in the state-funded program.

“There is a need in not only this community but in all communities for facilities such as what is being proposed,” Slaughter said. "So that we can help these folks get to a point in their life no different than the same point as one of the previous speakers.”

Henderson and others left the meeting complaining about their family's safety. Moore and Corbin waited for an escort to leave the area.

GPB is part of the Mental Health Parity Collaborative, a group of newsrooms that are covering challenges and solutions to accessing mental health care in the U.S. The partners on this project include The Carter Center, The Center for Public Integrity, and newsrooms in Arizona, California, Georgia, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Texas.