Section Branding

Header Content

Mental health advocates in Georgia say a lack of access to care is what leads to crises

Primary Content

Partners across behavioral health systems in Georgia say they want to build on the recently passed Mental Health and Parity Act. GPB’s Ellen Eldridge reports.

The Georgia Mental Health Policy Partnership is comprised of 14 organizations that represent a majority of Georgia's mental health and substance abuse peers, consumers, their families and their allies, Jeff Breedlove with the Georgia Council on Substance Abuse said.

The 2022 Unified Vision for Transforming Mental Health and Substance Use Care in Georgia is part of a multiyear legislative process. Last year, Unified Vision called for better access to mental health care as the state tackled effects from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since then, Georgia rose from the absolute bottom to rank 48 when it comes to access to mental health care.

MORE: Georgia improves its mental health rating — on data collected before COVID. But challenges remain

A focus from not only the groups associated with behavioral health advocacy but also legislators including state House Speaker David Ralston, led to the passage of the Mental Health Parity Act.

Now, the advocates want more funding to expand programs that have proven effective.

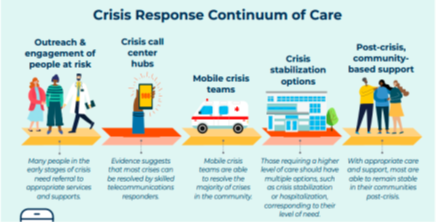

"We must focus on peer-led, recovery-based programs," Breedlove said. "House Bill 1013 was the beginning, not the end. There's still stuff to do on parity to make sure that state agencies are interpreting it with legislative intent, to make sure that we continue to build a peer-led workforce, and to make sure that we work on emergency crisis and response even further."

The largest mental health service provider in Georgia is its criminal justice system. County jails and prisons are filled with folks that have not properly given them access to mental health care, state Rep. Gregg Kennard (D-Lawrenceville) said last year.

"One can make an argument that we criminalize mental health," he said.

A lack of funding means that many parts of rural Georgia can't even afford to be part of a pilot program for coresponders, Breedlove said.

The Georgia Council on Substance Abuse aims to work with the state to expand the program of Recovery Community Organizations, which is an independent, nonprofit organization led and governed by representatives of local communities of recovery.

These organizations organize recovery-focused policy advocacy activities, carry out recovery-focused community education and out reach programs, and/or provide peer-based recovery support services.

"We have 40 of them in Georgia, but 40 is not enough to serve 159 counties," Breedlove said.

About 49% of Georgia high school students reported feeling intense anxiety, 40% said they felt depression, and 11% reported harming themselves on purpose within the last year, according to the Unified Vision.

Peter Nunn, a member of the board of directors of the Georgia Chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, said three of the foundational elements of the Unified Vision are:

- Early identification and prevention

- Workforce

- Parity

Inadequate provider networks are the primary problem for each of those three elements, Nunn said. Insurers’ provider networks are the crucial intermediary step between having insurance coverage and accessing medical care, but many insurers point to an overall shortage in the number of behavioral health care providers in an attempt to excuse their inadequate networks, Nunn said.

RELATED: With few other resources, people with behavioral health issues find treatment in jails and prisons

"That action, however, is nothing more than a verbal sleight of hand used by insurers to distract attention from insurers’ seemingly willful breaches of network adequacy obligations," Nunn said, citing a study by an actuarial firm, which found that Georgia’s children are forced to go out-of-network for behavioral health care more than 10 times more frequently than they are forced to go out-of-network for general medical care.

Nunn said that's because insurers have inadequate networks of behavioral health care providers for Georgia’s children.

"We're going to ask the state to expand existing programs in mental health and addiction services, which they know already work," Breedlove said.