Caption

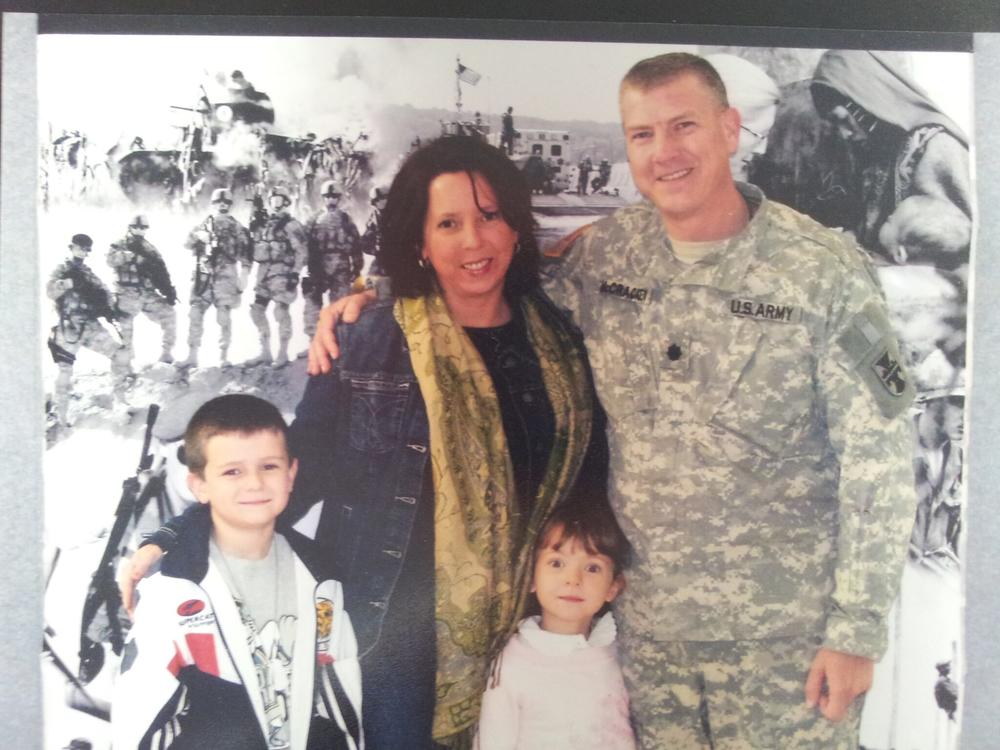

David McCracken (right) died of brain cancer in 2011 after serving in Iraq. He's seen here with his wife, Tammy, and their kids in this February 2008 photo. Sen. Raphael Warnock said he was moved to file a bill extending benefits to surviving spouses who remarry.

Credit: Contributed photo