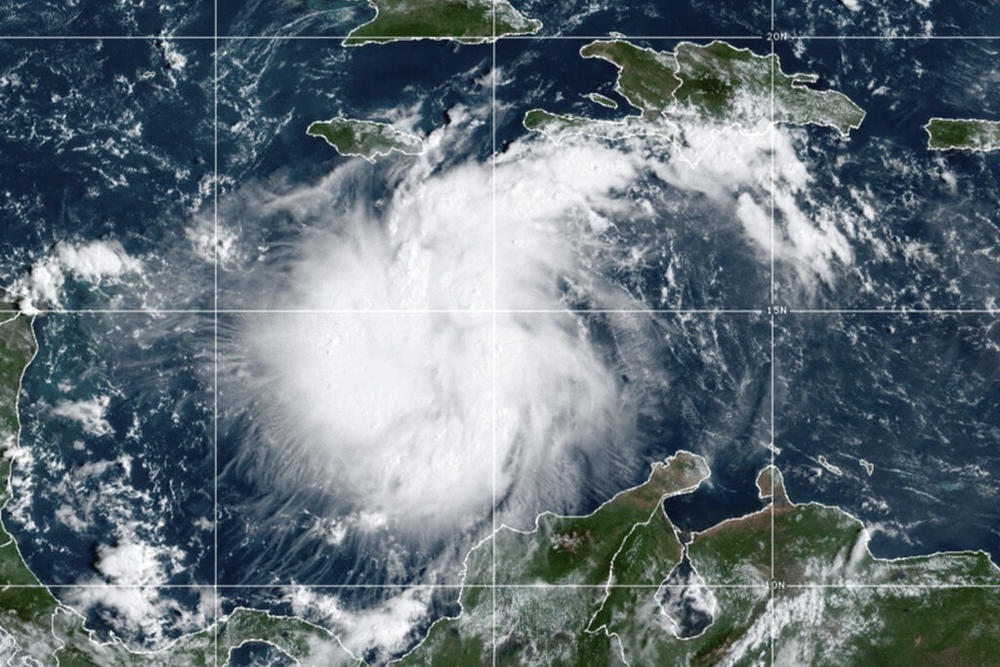

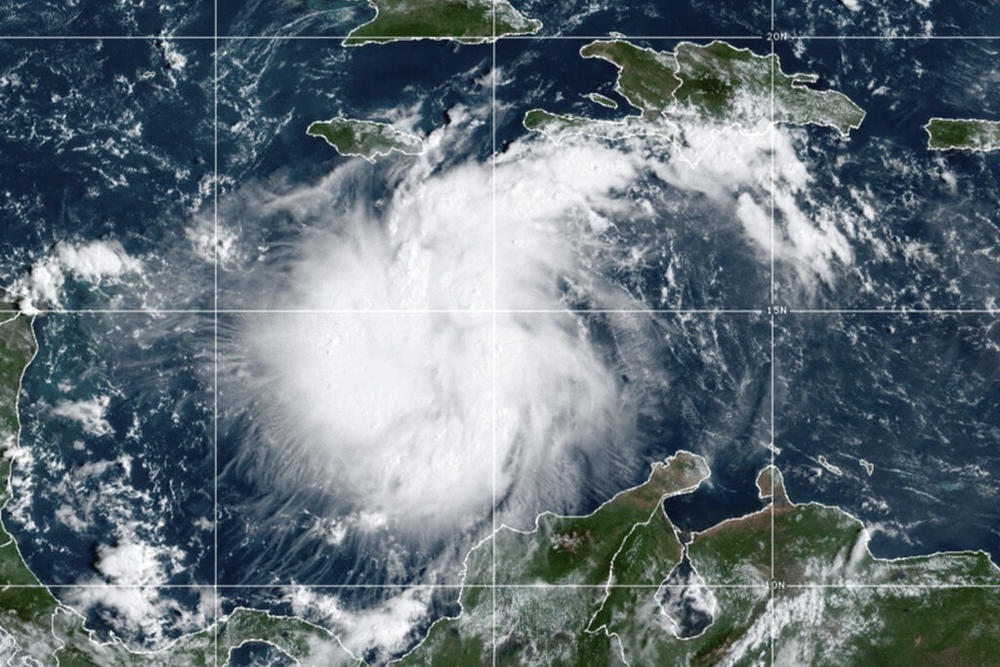

Caption

This satellite image provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows Tropical Storm Ian over the central Caribbean on Saturday, Sept. 24, 2022.

Credit: NOAA via AP

This satellite image provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows Tropical Storm Ian over the central Caribbean on Saturday, Sept. 24, 2022.

Mary Landers and Craig Nelson, The Current

As Hurricane Ian swept north through Florida, heading towards Coastal Georgia, Gov. Brian Kemp flew into Savannah to brief residents on preparations for the gale. Sen. Jon Ossoff urged residents to “take the storm seriously,” while Sen. Raphael Warnock urged calm and readiness.

Rep. Buddy Carter’s office provided a list of resources for those residents affected by the storm. Savannah Mayor Van Johnson and other municipal officials up and down the coast put emergency management plans on the ready.

Together, Georgia’s officials — especially those on the ballot next month — took pains to be seen and heard as Ian neared. After it was over, no one appeared to have dropped the ball.

This is due mainly to the fact that at least for Coastal Georgia, the hurricane was a “nothing-burger,” as one disappointed surfer on Tybee Island put it.

Yet with a slight shift in the storm’s path, it easily could have been different, St. Marys City Council member Jim Goodman told The Brunswick News.

“Had the storm run up the east coast of Florida as a Category 4, I’d be out of here,” said Goodman, the sole candidate for the Camden County Commission’s seat four in the midterm elections. “It would have been really bad.”

Going forward, the crucial question for state and local officials is what lessons can be learned from Hurricane Ian after the television cameras turn elsewhere and before a storm of similar scale occurs again, as it no doubt will — with possibly far more dire consequences for Coastal Georgia.

Certainly, the storm served as yet another reminder of the big picture: Growth in the region and elsewhere in the southeastern U.S. is putting more people in harm’s way.

From 2010 to 2020, the rate of population growth in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee surpassed the national average — Florida alone added a staggering 2.7 million people. Census projections suggest the Southeast will see the nation’s largest population gains over the next two decades, through 2040.

Hurricane Ian is also a reminder of the quandaries facing those government officials trying to address the costs of extreme weather while encouraging growth.

To our north, in Charleston, where the population grew 25% between 2010 and 2020, officials believe that climate change is an existential threat. Last year, the mayor said Charleston must “rezone every inch of our city” to put an end to development in flood-prone areas.

At the same time, plans are moving ahead for a massive residential and commercial development that environmentalists say is located partly in a flood plain.

More narrowly, Hurricane Ian renewed questions about the use of building codes, evacuations, and insurance for residents in vulnerable areas seeking to protect themselves and their property.

FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell told CNN on Sunday that anyone living near water should buy flood insurance.

“Just because you’re not required to buy flood insurance doesn’t mean you don’t have the option to buy it.” Fewer than five million policies are in force nationwide, FEMA reports.

Politically speaking, Kemp and other Georgia officials know that major storms provide a national spotlight and lots of media attention. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis knows that, too.

As the hurricane hurtled towards Florida from the Caribbean, he toned down his provocative political style to appear more collegial, especially to the federal government, on which his state depends for emergency assistance.

Politicians are also keenly aware that natural disasters can break, as well as make, a political career. The perils of ignoring such disasters — or appearing to ignore them — are woven into American political lore.

President George W. Bush never recovered politically from the perception that the federal government failed to respond adequately to Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

When a sudden storm quickly dumped 14 inches of snow on Washington in 1987, forcing the federal government, the local government, and businesses to shut down, then-Mayor Marion Barry was 3,000 miles away in California, playing tennis at the Beverly Hills Hilton and watching the Super Bowl, in which his hometown team wasn’t even participating.

Most politicians would have returned home. Barry did not, beginning his long slide from power.

Then there is that headline.

When city plows failed to clear streets in the borough of Queens for days following a blizzard in 1969, favoring Manhattan instead, the New York Daily News blared, “QUEENS CALLS MAYOR SCHMOBALL.”

The outcry forced Hizzoner, Republican John Lindsay, to change political parties. Lindsay managed to eke out reelection. But the “Lindsay Blizzard” and the mayor’s perceived neglect introduced the phrase “limousine liberal” into the American political lexicon.

Lindsay later retired to Hilton Head, where he died in 2000.

Whether DeSantis suffers anything close to that ignominy remains to be seen. But there are signs of a developing political storm.

The number of people in Florida killed by Ian increased to at least 100 yesterday afternoon. That toll is expected to increase. Questions also are starting to be asked over whether hard-hit areas received enough advance warning to evacuate. And then there are concerns over how the storm will affect Florida’s already floundering property insurance market.

Georgia officials are watching closely. Hurricane season continues through November.

The Tide brings news and observations from The Current’s staff. This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.