Section Branding

Header Content

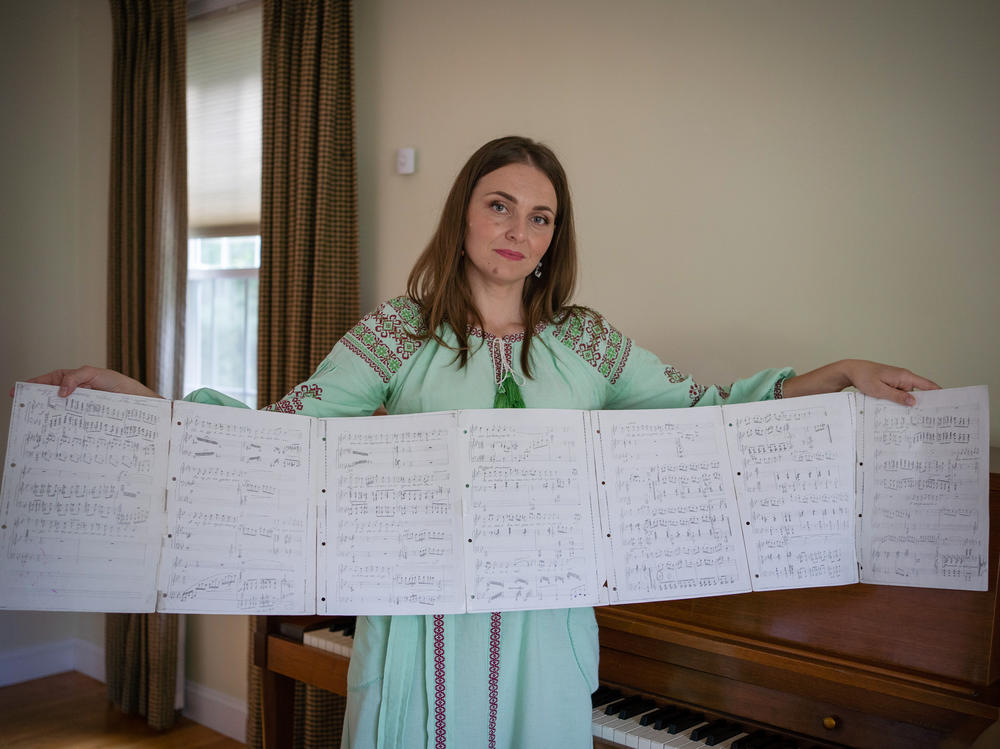

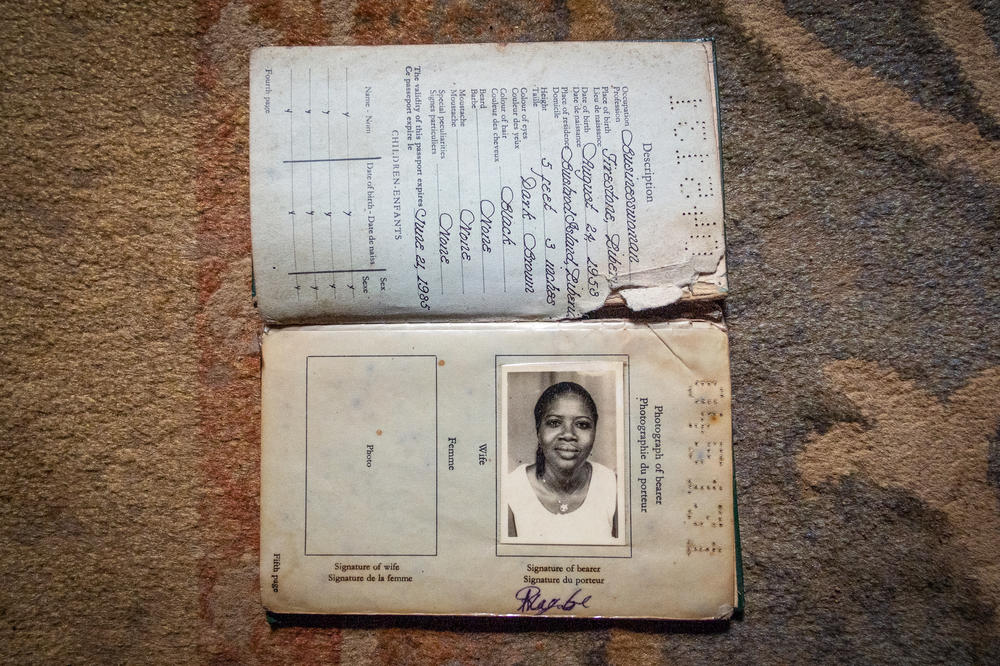

PHOTOS: If you had to leave home and could take only 1 keepsake, what would it be?

Primary Content

Maybe it's a piece of traditional clothing gifted by a parent. Or a bronze bowl used for religious ceremonies. Or a family recipe for a favorite dish.

These are all mere objects — but they aren't just objects. A cherished keepsake can serve as a connection to your family, your roots, your sense of identity.

This kind of memento takes on new importance if you have to leave your homeland and set off for a new country and an uncertain new life.

At this time of unprecedented numbers of refugees — a record 27.1 million in 2021 — we wanted to know: What precious possessions are refugees taking with them? The photojournalists of The Everyday Projects interviewed and photographed eight refugees from around the globe. Here are the objects they said give them comfort, solace and joy.

Editor's note: If you have a personal tale about a special possession from your own experience or your family's experience, send an email with the subject line "Precious objects" to goatsandsoda@npr.org with your anecdote and your contact information. We may include your anecdote in a future post.

For more details on the lives of the 8 refugees profiled below, read this story.

Additional credits

Visuals edited by Ben de la Cruz, Pierre Kattar and Maxwell Posner. Text edited by Julia Simon and Marc Silver. Copy editing by Pam Webster.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.