Section Branding

Header Content

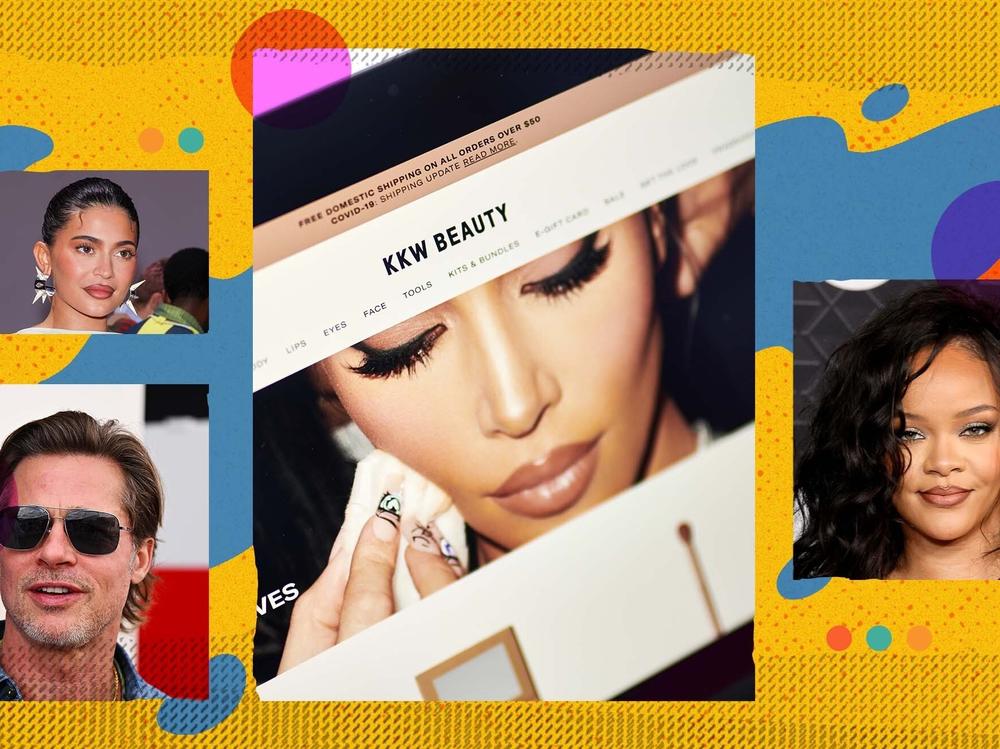

Skincare culture runs deep — and celebrities are cashing in

Primary Content

From Rihanna to Brad Pitt, celebrities everywhere seem to be starting their own skincare lines. And they all seem to promise to help us achieve healthy, glowing, youthful skin – just like theirs. And yet most of those stars didn't use their own products to get their clear, Hollywood-smooth complexions. So what are they really selling? And why can't we seem to stop buying in? In this episode of It's Been a Minute, cultural critic Jessica DeFino joins host Brittany Luse in breaking down why skincare can feel morally superior to makeup – all while the body positive movement has yet to extend above the neck.

This is adapted from an episode of It's Been A Minute. Follow us on Apple Podcasts or Spotify, and keep up with us on Twitter. These excerpts have been edited for length and clarity.

Interview highlights

Why skincare seems to be having a moment

Jessica DeFino: Oh, there are so many reasons why skin is having a big moment. Color cosmetics are sometimes seen as superficial or like a vapid pursuit. Skincare has all of these claims to health and wellness, so it's easier for people to feel like they are taking care of themselves that this is for their health, their well-being, even their mental health, and not feel like they're funneling time into perpetuating beauty standards, even though that is, for the most part, what skincare is as well.

The shifting meaning of 'good skin'

DeFino: I personally despise the term "good skin." I think good skin is an excellent example of how beauty has been wrapped up in morality. Beauty functions in society as an ethical ideal. And we have been fed messages since the minute we pop out of the womb: to be a good person is to be a beautiful person.

The idea of good skin [does] shift over time as beauty standards and beauty trends do. Currently, the ideal of good skin is very smooth, extremely shiny and wet looking. There is no allowance for changes in tone or texture. It's very flat and glass-like. It reflects the state of our largely virtual digital lives. We're expecting our faces to look like a screen. ... And it's so interesting because when you look back on the history of beauty standards, this isn't a new phenomenon. When movies first came out and we could see actresses on the screen, the lighting wasn't that great, the camera quality wasn't that great, and it led to this sort of blurred, ethereal look. And all of a sudden people were like, "This is what somebody famous and worthy looks like. I want to look like that, too." Every advancement in screens – in cinema, in digital – has had that moment. And we are trying to adapt our real life human faces to a virtual, hyperreal standard of beauty.

On Kim Kardashian saying she'd eat poop to look young

DeFino: I think it says a lot about the state of modern beauty marketing and modern skincare marketing, because in that very same New York Times interview, The Times noted that her skincare line [does not] use the term "anti-aging" to market any of her products. They don't want to use this negative connotation of anti-aging. However, when you come out in that same article and say that you would eat excrement to look younger, you're perpetuating anti-aging ideology. This is a really important thing to note, because in the beauty industry at large, we are seeing a backlash to negative sounding terms like anti-aging. But the underlying ideology hasn't changed. Our society and our beauty industry is more youth obsessed than ever. It's just that these messages are more being told in the underlying marketing stories, in the models being used, in the products being pushed in, the injectables being normalized. We are living in a youth glorifying culture. Even if we [don't] say anti-aging.

Brittany Luse: To bear down on this a little bit more, why do we not want to use the term "anti-aging," and still don't want to age?

DeFino: Anti-aging is ageism, plain and simple. We live in a deeply ageist society. We value members of society largely for their productivity. Your productivity and your value to the economy wanes the older you get. We don't have equity for the elderly. We don't have sufficient medical care for the elderly. We don't have a lot of resources that would make aging seem like an appealing proposition. We also live in a very surface-level society. So if we can take away some of our age anxiety by temporarily erasing our wrinkles with a shot of Botox, we're going to go for that because we have been trained to want a quick and easy sweep-it-under the rug fix for what is actually a societal problem.

The shortcomings of the body positive movement

DeFino: Body positivity has rarely extended above the neck in popular culture, which is always concerning to me. The standard of beauty is a set of parameters. There's some room for change – I think people can understand the idea of like, "Well, maybe I'm fat, but I have such a pretty face." And so these parameters still exist, and the body positivity movement did not address those parameters at all. So we see a lot of body acceptance influencers like Katie Sturino now preaching about accepting your body and loving your body, and funneling the brain space that they have freed up to worrying about their face.

Something that I always like to say is that skincare culture is just dewy diet culture. And you can make these really easy swaps to see if a piece of content feels right to you. So for instance, I think in Katie Sturino's Botox post, she was talking about erasing her frown lines. But if you swapped the words, "frown lines" for "stretch marks" – [does it] still feel good if it was telling you you had to get rid of your stretch marks? There's really no difference between these. And I really hope we can see how we've been collectively bamboozled by diet culture and beauty culture and skincare culture.

On the pressure to subscribe to beauty standards

DeFino: Beauty is an inherent human longing. When I'm critiquing the beauty industry, I am critiquing the industrialized, standardized portions of it. And I never mean to diminish the power and the importance of beauty in our lives. I think of beauty as being up there with freedom, truth and love. These are inherent human longings. ... We can appreciate the beauty of nature. We can appreciate the beauty of a piece of artwork. We need that kind of beauty in our lives. Part of what makes the beauty industry so powerful is that it co-opts this instinctual need, this instinctual craving for this free, beautiful, energetic, three-dimensional version of beauty, and it flattens it into one dimension and it says beauty is only physical, and beauty can only be achieved through these products and these procedures with this money.

And it really sort of bamboozled us into believing, "OK, that's the beauty that my spirit is craving." And that's also why it's so unfulfilling. We keep buying and trying to make ourselves look different because that inherent human longing for beauty is not satisfied by the physical, standardized, industrialized stuff. I don't have an answer for it. I don't know how we connect with that kind of beauty. But that's what keeps me going. That's what keeps me interested.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.