Section Branding

Header Content

How title lenders trap poor Georgians in debt with triple-digit interest rates

Primary Content

Magaret Coker, The Current, with ProPublica's Joel Jacobs and ProPublica's Mollie Simon

When Robert Ball turned 63, he was looking forward to retirement in his wife’s hometown of Savannah, Georgia. The couple had a comfortable house with a lush garden, the certainty of his pension and the hope of spending more time with their grandchildren.

That dream shattered when Ball’s wife, Gloria Ball, developed severe health problems. They faced huge medical bills, yet their bank refused to refinance their mortgage. Left with few options for raising cash, Robert Ball drove to TitleMax, a business that prospers in Georgia’s banking deserts and lends money at terms that would be illegal for other financial institutions. “I was desperate” for quick cash, Ball said. “They welcome folk like me.”

In July 2017, Ball signed a contract to receive $9,518 from TitleMax in exchange for a lien on the title to his 2006 Honda Ridgeline truck, money that the couple used to pay for Gloria’s medical needs. The terms of Ball’s contract were typical for TitleMax, specifying that he would have to repay the money plus interest in 30 days. But the store manager explained that, as long as he paid $1,046 each month, he could extend the contract indefinitely and keep his car — on which he had no other debt — from being repossessed by the company. What the manager did not mention, Ball said, was that his payments would only cover interest.

For two years, Ball made his payments diligently, court records show. Then the company told him something that nearly made him fall down: Even though he had paid more than $25,000 by then, his principal hadn’t budged.

TMX Finance, TitleMax’s parent company, calls itself a community resource to its 293,000 customers, people written off as credit risks by traditional lending institutions but who need financing to pay for life’s basic needs. As the nation’s largest title lender, TitleMax thrives on an innovative business model that lends money to risky clients in exchange for collateral: the title to the vehicle in which the customers drove to the store. In 2019, TMX Finance reported $910 million in revenue, primarily from its TitleMax brand.

Rather than seeing the company as a force for good, a growing consortium of lawmakers, religious leaders and consumer advocates believe TitleMax, and its industry writ large, to be predatory leeches on the growing ranks of working-class Americans. More than 30 states prohibit title lending or have laws inimical to the industry. In 2016, TMX Finance paid a $9 million fine, approximately 1% of the company’s revenue that year, to the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which ruled that the company misled customers about the full costs of its loans in Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee. Since then, at least five states have passed laws capping interest rates that title lenders can charge at 36% per year.

Georgia, however, has bucked this trend. Nearly two decades ago, the state made it a felony to offer high-interest payday loans that state lawmakers described as usurious. Yet state law allows title lenders to charge triple-digit annual interest rates. This has helped the industry grow like kudzu throughout the state, which is home to three of the nation’s top title lenders.

The Current and ProPublica spent seven months examining the operations of TitleMax, the dominant industry player in Georgia, based on hundreds of pages of internal company documents, interviews with current and former company officials and an analysis of storefront locations as well as vehicle lien records from the Georgia Department of Revenue’s motor vehicle division. The investigation offers for the first time a window into the scope and scale of the company in the state, as well as the impact on its target customers: the working poor and communities of color.

The Peach State is TMX Finance’s second-largest market, accounting for 20% of its business volume as of June, according to a financial ratings report by S&P Global Ratings. Only Texas, which has nearly three times the population of Georgia, was larger, representing 32% of the company’s business volume. From July 2019 through June 2022, roughly 210 TMX Finance stores in Georgia issued new “title pawns” for approximately 47,000 vehicles annually, under brand names TitleMax and TitleBucks. They represented more than 60% of the state’s total volume.

Annual interest rates in typical TitleMax contracts ranged from 119% to 179%, and title pawns — even though they are structured to last only 30 days — often remain active for multiple months, or even years.

‘There is no recourse. Title lenders operate a business that…is entirely legal in Georgia. It’s a terrible place to be powerless, poor or just down on your luck.’

— bankruptcy attorney Lorena Saedi

Despite offering a product that customers say feels like a loan, TitleMax and its competitors aren’t considered lending institutions under state law. Instead, the title-lending industry works under Georgia’s pawn shop statutes, a loophole that exempts it from the usury laws and state oversight that other subprime lenders in Georgia must operate under. Title pawn contracts, meanwhile, are not amortized like home mortgages, which offer customers a set schedule to pay off their loans. Critics say this practice creates a debt trap — which is profitable for companies and bad for consumers like Ball.

TMX Finance did not respond to repeated requests for comment on a detailed list of questions about the company’s operations.

“Privately there is not a legislator in Georgia who doesn’t feel like it is a scourge on our state, but publicly there aren’t many willing to take on” the title-lending industry, said Liz Coyle, the executive director of Georgia Watch, a consumer advocacy group that has pushed for regulatory reform for title lenders for roughly 15 years. “Their clout is too great, and political will is too weak.”

State Sen. Lester Jackson, a Black military veteran who represents Savannah, has voted against more regulation for his hometown company, arguing that title lenders fill a necessary gap for his constituents, given the lack of equity in the traditional banking sector.

“Banking deserts are real” in Georgia, said Jackson, a Democrat. “Sometimes, this is all that the community has.”

For customers like Ball, the power imbalance favoring TitleMax in Georgia feels like being caught in an undertow.

At age 71, Ball declared bankruptcy, seeking relief from his debt burden. Even then, TitleMax pursued him. The company threatened to repossess his car, sell it and keep the profit. It then went to court to assert its right to do so — and won.

Past the gilded dome of Savannah’s city hall and along the azalea-lined Johnson Square sits an unobtrusive two-story brick building from which privately held TMX Finance and its founder and sole shareholder Tracy Young run the nation’s largest title lender.

Unlike other Savannah-based corporations, TMX Finance and its biggest brand, TitleMax, keep a low profile. No corporate sign graces its headquarters. The company rarely sponsors local charity events. When TMX Finance needed money to expand its business operations, it turned to private investors rather than a public stock listing. When it’s sued, the company moves swiftly to seal documents that might reveal even its most mundane business details.

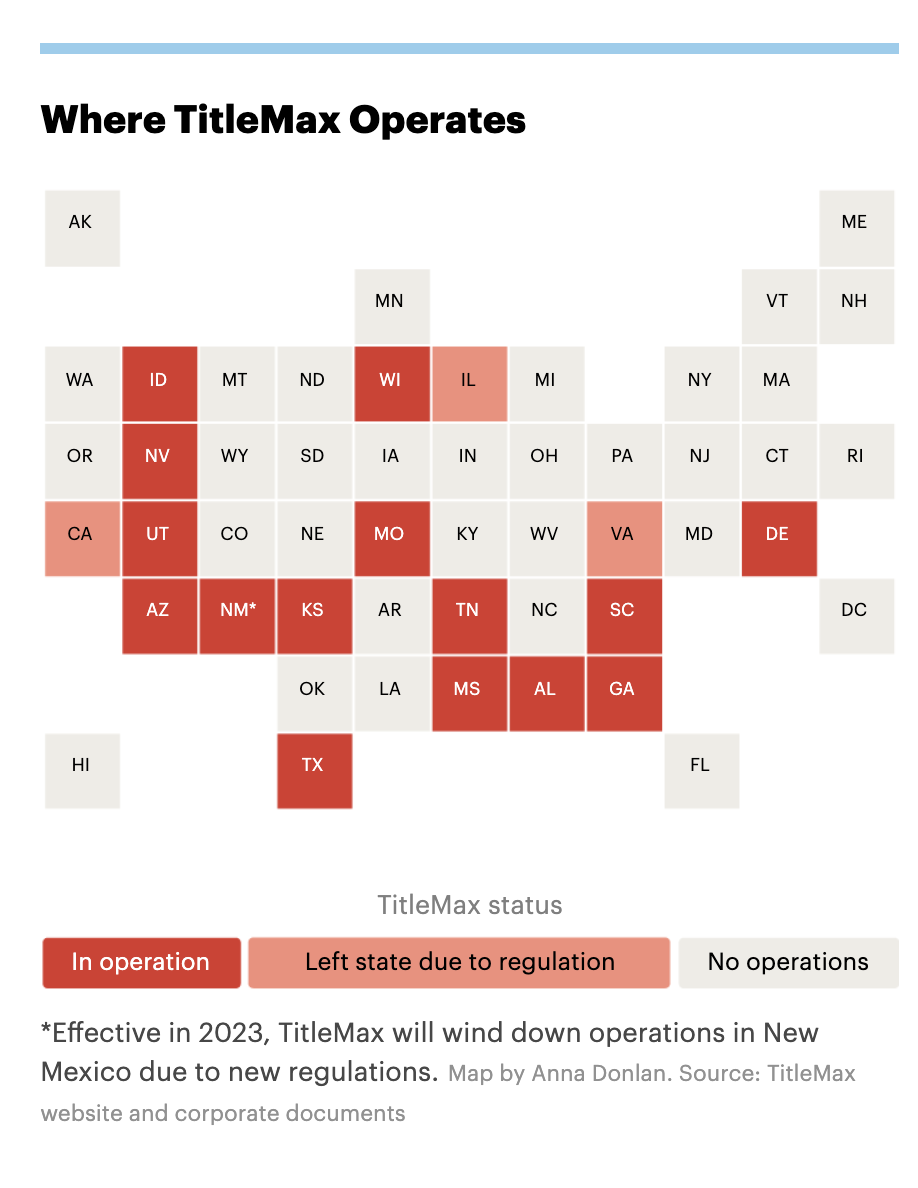

Young, a one-time pawn shop owner, relied on this impenetrable business culture as he built the company from two retail locations in Savannah and Columbus, Georgia, in 1998 into a national juggernaut. The company now operates in 16 states and has nearly 1,000 stores. In 2019, TMX Finance reported its most successful year ever, according to S&P, with revenue topping $900 million that year. (Revenue dropped to $753 million in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, and then to $712 million in 2021, after the company closed operations in three states after regulations there were tightened.)

Georgia has emerged as a critical profit center for TitleMax, with some stores making more than $1 million in gross revenue per year, according to tax documents and former store managers who requested anonymity to speak about internal company procedures. That’s despite Georgia’s history as a vanguard against some parts of the fringe financial services industry.

In 2004, Georgia lawmakers cracked down on payday lending, an industry that offered triple-digit-interest loans to people in need of cash in between paychecks. They closed loopholes that had allowed the industry to evade long-standing usury laws in the state and made offering payday loans a felony. The lawmakers — many of them proud churchgoers — considered such loans to be both unchristian and unfair, according to Chuck Hufstetler, a Republican state senator who has voted for more regulation for title lenders.

The Georgia Department of Banking and Finance regulates and licenses other subprime lenders that offer loans to customers considered high risk. For instance, the 166 installment lenders working in the state are subject to Georgia’s usury cap of 60% annually, including interest and fees.

Yet lawmakers in Atlanta also passed a law that allowed the burgeoning title-lending industry to operate outside these regulations. Since then, TitleMax and at least 90 other title-lending companies in Georgia have operated under state pawn shop statutes, rather than financial or banking laws.

The bar to open a title-lending business in Georgia is low. A company must apply for a pawn shop license for their employees from the local government in the city or county where they work. With that in place, “title pawn” stores can offer customers a 30-day contract at an interest rate up to 25%. State law allows these contracts to be renewed for an additional two months at that same monthly interest rate. After that, additional renewals have a lower interest cap of 12.5% per month, but that combined rate — up to 187.5% annually — is still far above the usury caps for other types of lenders in Georgia. Title lenders have no obligation to assess customers’ credit or their ability to repay what they borrow or to report the number of title pawns issued to state regulators.

Only a few states offer similarly permissive operating landscapes for title lenders. Alabama, the only other state where the industry works under pawn shop statutes, allows title pawns with up to 300% annual percentage rates. Texas also permits triple-digit rates, with no caps on the total amount of title loans or their fees.

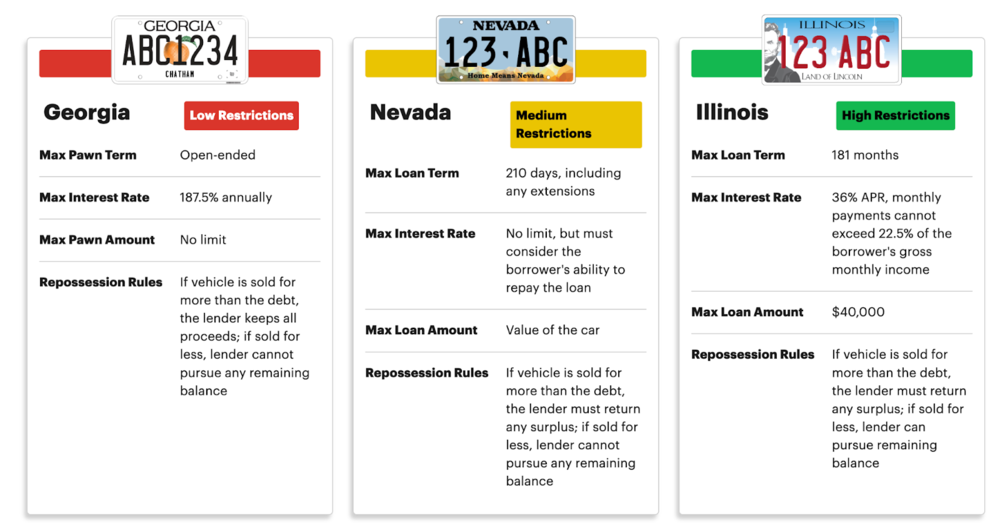

At least 20 states have laws that cap interest rates at 36% or less per year for title lenders — or 3% per month. Several other states have set loan terms for fixed periods or require the principal to be paid down as a condition of renewal, which limits customer costs of borrowing and title lenders’ maximum profit.

How title lending is regulated in 3 states

In Georgia, title lenders operate under pawnshop statutes that permit triple-digit interest rates and allow pawn contracts to be renewed indefinitely — rules far less restrictive than laws in most other states.

The increased regulations coincide with a growing body of evidence about the harm that subprime lenders like title-lending companies have on local communities and economies.

Illinois’s path to regulating the industry is instructive. In 2012, when TMX Finance executives identified the state as a growth market, regulators were already putting into place rules that mandated reporting from subprime lenders like title-lending companies working in the state.

In 2020, Illinois church groups and state lawmakers reviewed nearly a decade’s worth of data and became alarmed. High interest rates and fees charged by title lenders were exacerbating pockets of poverty, especially in minority neighborhoods, according to Brent Adams, the then-state official who helped devise the reporting regulations. Individual families were more indebted, and fees they paid were largely going to out-of-state lenders, leaving less money to be spent in local businesses. Moreover, customers who couldn’t keep up with their payments to title lenders would lose a working family’s most important asset: their vehicle. Without a car, a parent could be unable to hold down a job or get children to doctors or school, he said.

“It is difficult to craft a data argument for these products. Practically everyone you talk to pays three times the amount of the loan to get out of a title loan,” said Adams, who is now senior vice-president for policy and communications for the Woodstock Institute, an Illinois-based economic think tank. “Some people will say they had a good experience, but the percentage of people who report an abusive relationship with title lenders is so much higher. The disparities are extreme.”

In early 2021, the Illinois legislature passed a 36% interest rate cap, dismissing arguments from TitleMax and its industry that such a move would put them out of business. That year, TMX Finance stopped making new loans in the state. Virginia and California passed similar interest rate caps, moves that led TitleMax to close operations in those states as well, according to state officials and the company’s website.

A similar attempt in Georgia in 2020 died after TMX Finance’s then-chief legal officer testified at a state senate committee hearing that TitleMax needed to charge high interest rates given the risk profile of its customers. State senators did not press the company for more detail, nor did any senator offer up dissenting data.

Over the last 16 years, at least five attempts in Georgia to pass legislation regulating interest rates charged by title lenders or reclassify them under financial lending rules have wilted under industry pushback. TitleMax, for one, says strict interest rate caps would endanger the approximately 700 jobs the company provides to Georgians.

Tameka Rivers, a middle-aged Black woman who lives in east Savannah, has been paying off a TitleMax pawn for more than two years. Rivers said she was desperate for $2,000 back in 2019 to help her adult daughter, who was expecting a baby and needed a place to live. A single mother working two jobs to provide for an extended family, Jones didn’t have savings to help provide her daughter with a security deposit for her apartment lease. She also didn’t have relatives she could rely on for help.

Rivers remembered hearing TitleMax’s signature advertisement on the radio: “Get your title back with TitleMax,” goes the catchy jingle. That was enough for her to drive over to the TitleMax store on Skidaway Road, a mile from Georgia’s oldest historically Black university, to see if they could help.

“It seemed straightforward enough at the time,” Rivers said. “They didn’t ask me a lot of questions about my life, and, boy, we needed the cash.”

Consumer advocates in Georgia have long argued that struggling families like Rivers’ deserve better financial options than the one TitleMax and its industry offer. Yet revealing the scope of the impact title lenders have on these families is challenging because of the lack of public data on the industry.

The Current and ProPublica identified roughly 500 title pawn stores, which span the majority of Georgia’s 159 counties, including at least a dozen locations in Atlanta and Savannah, as well as in rural areas in and around Ellijay and Vidalia.

Georgia does not officially track the number of title pawns issued by these stores. The analysis of the records of vehicle liens placed by these companies reveals new title pawns for roughly 75,000 vehicles per year since mid-2019, when the state implemented a new system for tracking vehicle ownership information. That figure is likely an underestimate of the total number of title pawns, since the analysis does not include repeat customers.

The industry is thriving at a time when the number of traditional banking locations in Georgia has declined by 22% in the last decade, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. A 2021 FDIC survey found that 6.7% of Georgians lack bank accounts. That statistic is roughly twice as high — 13.3% — for Black households.

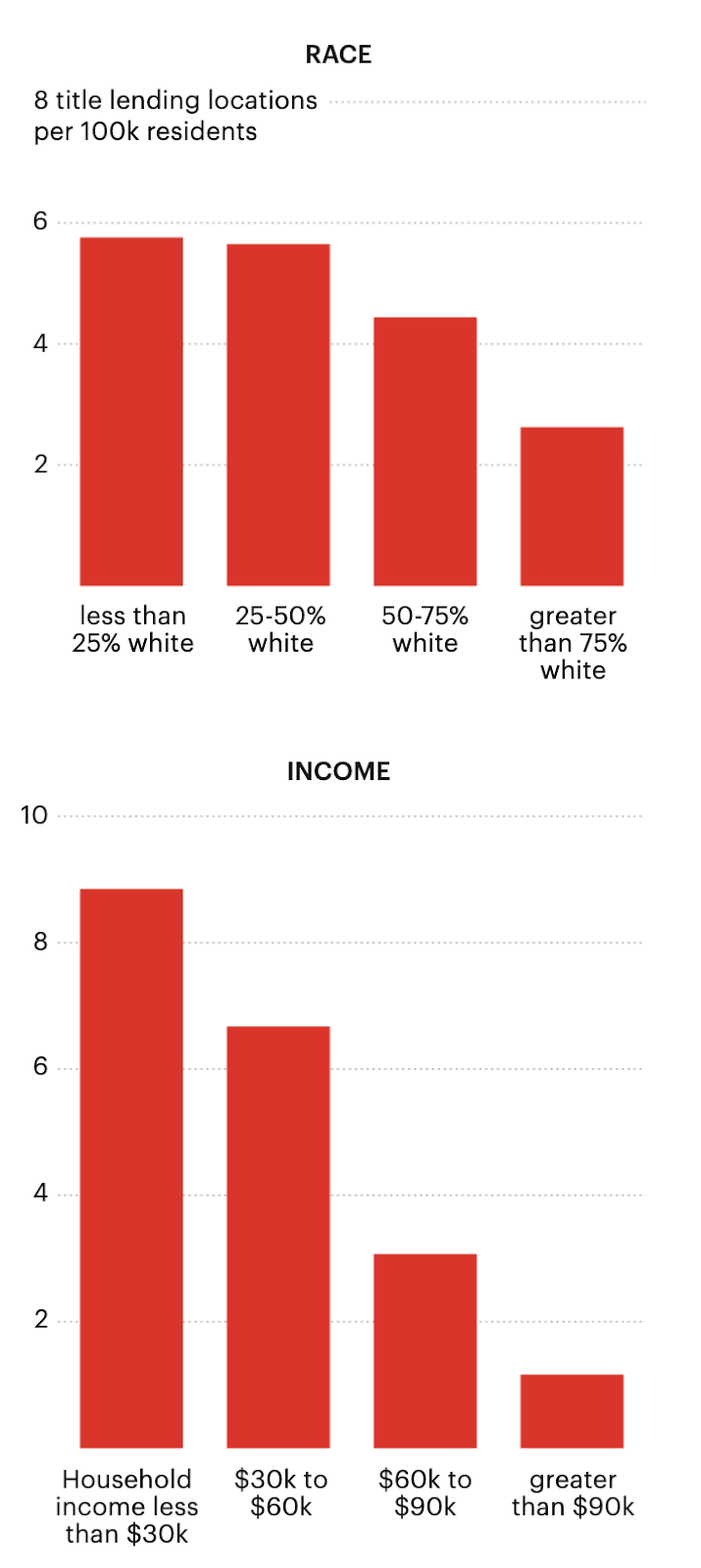

Title lenders are disproportionately located in communities of color and low-income areas, according to an analysis by The Current and ProPublica. Roughly three-quarters are in ZIP codes with incomes below the state’s median income.

Title lenders cluster in disadvantaged communities

Title lenders are less common in ZIP codes with more white residents or more high-income residents.

Source: Georgia Department of Revenue; Google Maps; company websites; 2020 5-year American Community Survey

But the industry’s impact on these communities isn’t captured fully by where they have storefronts. Equally crucial is how many months customers continue to pay, according to current and former industry officials.

Back in 2009, then-TMX Finance President John Robinson explained to the company’s creditors that repeat customer fee payments were the crux of TitleMax’s business plan. We “recover in excess of 100% of the face value of the Customer Loans,” he wrote in an affidavit. “The average thirty (30) day loan is typically renewed approximately eight (8) times, providing significant additional interest payments.”

Rivers told The Current and ProPublica that she wasn’t offered a formula describing how she would pay off her pawn. Instead, she said, the store manager emphasized the relatively low monthly payments of $249. Rivers said she doesn’t recall anyone explaining the difference between a payment that covered interest and one that included paying down her principal. After the manager talked through the monthly payment, she signed a contract on the store’s digital tablet. She had access to her data via a company app, which also allowed her to make payments electronically. But she rarely used the app and generally paid her monthly payments in cash.

Ten months later, after Rivers had paid TitleMax more than the $2,000 she had borrowed, Rivers talked to the manager who had set up her contract. That’s when she realized that she had only been paying interest and still owed the original pawn amount.

When Rivers complained about feeling deceived and asked for help working out a repayment plan to get out of debt, TitleMax wasn’t willing to help, she said.

District directors have the authority to rewrite contracts, but rarely do, according to two former managers who worked in Savannah and Columbus and who requested anonymity to speak about internal company procedures.

In October, Rivers’ daughter went to the hospital for a cesarean section, and now Rivers is helping care for a newborn, as well as four other grandchildren, while trying to juggle vocational school courses. She doesn’t know where she’s going to scrape together money to get rid of the TitleMax debt, she said.

Consumers who feel taken advantage of by title lenders in Georgia have a very narrow avenue for pursuing their complaints.

The CFPB, the federal agency created to protect consumers from big financial organizations in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, launched its investigation into TMX Finance, in part, due to consumer complaints amassed by Georgia Watch, the state’s most prominent consumer advocate. The company denied any wrongdoing, but the CFPB ruled in 2016 that it had deceived customers in Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee by masking the true cost of title loans. This did not impact individual cases, however, and the company’s $9 million fine was not paid out as restitution for individuals, instead going into an agency-controlled fund.

At the state level, the website for the Consumer Protection Division of the Georgia Attorney General’s Office has a whole page devoted to title pawns — but it is not directly linked from its homepage.

On that page, the agency categorizes title lenders as a fringe banking product similar to a “payday loan,” a product illegal in Georgia. It recommends that Georgians in need of emergency finance consider multiple alternatives, such as asking a relative for money or approaching a credit union, before turning to subprime financial products like title pawns.

For those who don’t find alternatives, the agency’s website offers straightforward guidance: If customers think their title lender violated the law, they “should notify the local criminal authorities for the city or county in which the title pawn company is doing business.”

Outside of metro Atlanta, few law enforcement bodies across Georgia’s 159 counties have robust white-collar or financial crime department or an investigator specialized in such crimes. LaGrange Police Chief Louis Dekmar, who has led the northwest Georgia department for nearly 30 years, said he doesn’t know of any local district attorneys who have filed charges against title lenders. The probability of that happening is slim, according to Dekmar and two other veteran Georgia police officials. Title pawn customers who may be victims “generally don’t know how to report something like that,” said Dekmar, a former president of the International Association of Chiefs of Police.

Meanwhile, the state attorney general’s office has not investigated TitleMax, despite the CFPB findings of abusive practices and that agency’s ongoing investigation, according to an official in the office.

The attorney general’s office has taken action against two other title lenders. In 2017, it settled with a TitleMax rival, Tennessee-based First American Title Lending of Georgia, for more than $220,000 to resolve allegations that the company had threatened individuals who were delinquent in repayments with criminal arrest warrants and by marketing its products as “loans” instead of “pawn transactions.” In the settlement, First American admitted no wrongdoing.

In 2018, the attorney general’s office reached a settlement with Georgia-based title-lending company Complete Cash Holdings and its owner Kent Popham, who agreed to pay a total of $35,000 “in response to allegations that it engaged in unlawful practices” against customers who had defaulted on their title pawn contracts. The company earlier denied wrongdoing.

“Consumers who seek out title pawns are already in financial straits,” Attorney General Chris Carr said in a press statement at the time. “Our office is committed to protecting vulnerable consumers from companies that try to take advantage of them through illegal actions.”

On other occasions, however, Carr’s office did not act. For instance, a testy five-year civil lawsuit in Fulton County Superior Court between TitleMax and subsidiaries of Alpharetta-based Select Management Resources surfaced a number of allegations of illegal behavior, including bribery and stealing customer information. TitleMax denied the allegations, and the two sides ultimately settled and moved to dismiss all allegations with prejudice in 2019. Kara Richardson, a spokesperson for the attorney general, said her office was aware of the case but declined to comment on specific allegations against those two companies.

Coyle, the head of Georgia Watch, said she’s disappointed that weak consumer laws tie prosecutors’ hands. “Municipalities can only do so much,” she said, referring to what she calls abusive behavior by the title-lending industry.

Sitting at his tidy ranch house in a leafy neighborhood in south Savannah, Robert Ball has a difficult time describing just how shocking it was when he realized in the summer of 2019 the extent of his debt with TitleMax.

Ball had become his wife’s full-time caregiver. Gloria was frail and barely had energy to get out of bed. Doctors had told him she had little time left. His sorrow was compounded by a second fear. Amid their increased medical bills, Robert had fallen behind on their mortgage payments. “When I was coming up, there were not a lot of Black folks who owned their home. If you have that roof, that is a sacred thing,” he said. “I was facing the loss of my wife. No way I could handle losing our home as well.”

On July 1, 2019, before the Fourth of July holiday weekend, Ball went to the TitleMax store on Abercorn Street to make his usual monthly payment. He asked the manager he had dealt with for two years just how much more was left on his debt. The manager looked up his account on her computer screen and delivered the crushing news.

Ball’s principal remained at $9,516 — just $2 less than the original amount of his pawn, according to court documents.

It had never occurred to Ball that his dedicated monthly payments weren’t paying down his principal. He assumed that, like a bank loan, if he paid what TitleMax told him to, he would eventually pay off the debt.

“It was a terrible feeling. I mean, I worked my whole life, for 38 years. I thought we were going to enjoy our retirement together. Instead, we were facing this kind of catastrophe. It’s a shameful situation for people like us — to be in debt,” Ball recalled.

He argued with the manager, but that didn’t change the ledger on her computer screen.

Ball didn’t know how to get his financial affairs in order, all while tending to his dying wife. He then got some unsolicited advice from a friend: Declare bankruptcy and try to get into a debt repayment plan. In Georgia, individuals who file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy work through a federal trustee to create a court-approved plan to repay creditors, often at steeply reduced rates. This was a solution, his friend advised, to keep the family house safe.

Ball, who spent his life as a medical tech delivering blood for the Red Cross, swallowed his pride and did it.

But the U.S. trustee appointed to Ball’s case had some more unwelcome news. His TitleMax pawn couldn’t be wrapped into a settlement with creditors. The company had status as a secured creditor due to Georgia’s pawn statutes, and would have to be paid back first and at the original terms of the title pawn.

Lorena Saedi, a bankruptcy lawyer and managing partner of Saedi Law Group in Atlanta, said stories like Ball’s are not unusual. At least once a week, she sees clients who are struggling with debt traps set by title lenders, and around a third of her bankruptcy cases include title lenders.

“There is no recourse. Title lenders operate a business that, while obviously immoral, is entirely legal in Georgia. It’s a terrible place to be powerless, poor or just down on your luck,” Saedi said.

Six months after Robert Ball filed for bankruptcy, Gloria died. Ball eventually paid off TitleMax.

Now, the 75-year-old spends his time trying not to drown in bitterness. Spending time with his daughter and grandchildren helps. Yet as he crawls out of the seven-year credit shadow caused by his bankruptcy, Ball prays that his old car doesn’t break down, and that he doesn’t need any expensive medical help himself.

“I have no safety net. I only have Jesus,” Ball said.

Students in the Covering Poverty Project at the University of Georgia’s Cox Institute for Journalism Innovation, Management and Leadership contributed research. Reporting for this project was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

This story comes to GPB through reporting partnerships with The Current and ProPublica.