Section Branding

Header Content

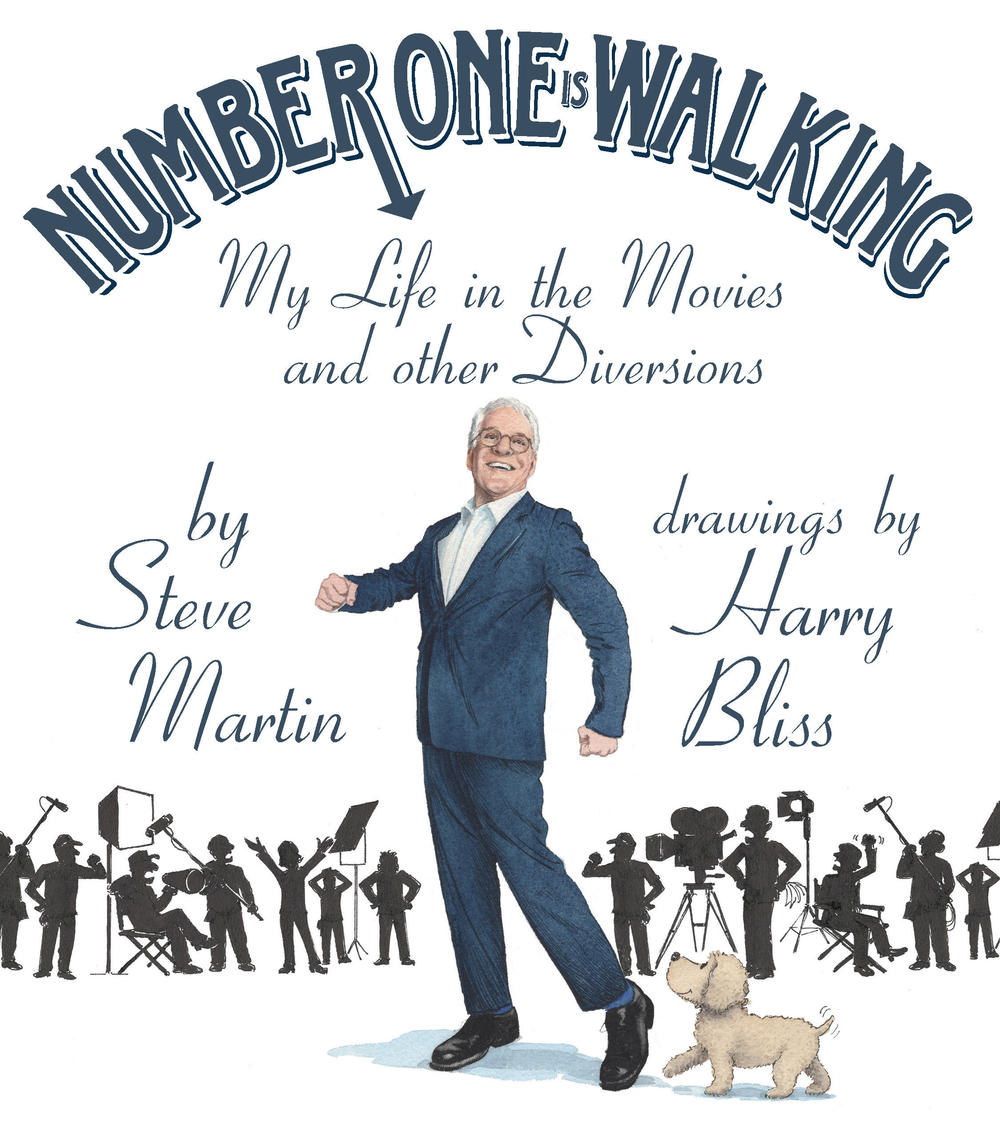

Steve Martin tells the story of his career — through cartoons

Primary Content

Steve Martin has been a renaissance man for decades.

His career has ranged from stand-up, to Saturday Night Live, to banjo playing. He's been in what feels like a million movies, and he's been lauded for his latest success, the series, Only Murders in the Building.

At the heart of his multi-hyphenate status is a passion for writing that ranges from novellas, to plays, to movies. That's why it's notable that to tell the in-depth story of his film career, he chose an new medium: cartoons.

The book, Number One is Walking, is a collaboration with The New Yorker cartoonist Harry Bliss. It's the second work from this pair, and is out November 15.

Steve Martin and Harry Bliss joined All Things Considered to share the experience of collaborating to tell the story of Martin's life through pictures.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Interview Highlights

On why they chose this medium

SM: I did a memoir of my stand-up career, and I did that in 2007, and it was called Born Standing Up. And the reason I limited it to that tale, was it had a beginning, a middle, and an end.

I started as a young, whatever, actor-comedian, and then I became the stand-up comedian and then I quit. So it had a stopping point. It had a philosophy to tell it. It had soul, I would say. And then I often thought about my movie career, but I always thought, well, I always think biographies and autobiographies are really interesting before you make it, and then after you make it, it's like, "Yeah, OK, and then I met, and then I did this, and then I did that."

I thought, I have these anecdotes and I don't want to do a book of anecdotes because often times they're tiny. They're little, tiny things. And then I started working with Harry, who I started writing cartoons for The New Yorker with, and then we did a book together of cartoons.

I approached Harry, I said, "Would you be interested in drawing up these anecdotes?" Because an anecdote in cartoon form is very succinct. You don't have to set the scene. You don't have to describe what people are wearing. You could just do the gist of the story.

So I thought, this is a perfect vehicle to do this because there's certain stories I just love and there are certain memories I love.

On the collaborative experience of illustrating someone else's life story

HB: I live in the woods, very rural. And how this came about and how I would get these anecdotes is sometimes he would email me. But on one day, he called me, and I was hiking in the woods, and I had taken a small dose of psychedelic, and I was feeling really good. And the phone rang and I felt it vibrate in my pocket. And I looked, and it was Steve. And I thought, well, I think I can handle this.

So I answered the call and he told me this really funny anecdote about Selma Diamond. And so he told me and I laughed out loud. And I got off the phone and I said, "Well!"

I was just standing there in the snow in the woods of New Hampshire. I will describe it in a way that David Byrne described: How did I get to this place? Where did this house come from? And this beautiful wife come from? How did I get to this point? It was a beautiful moment.

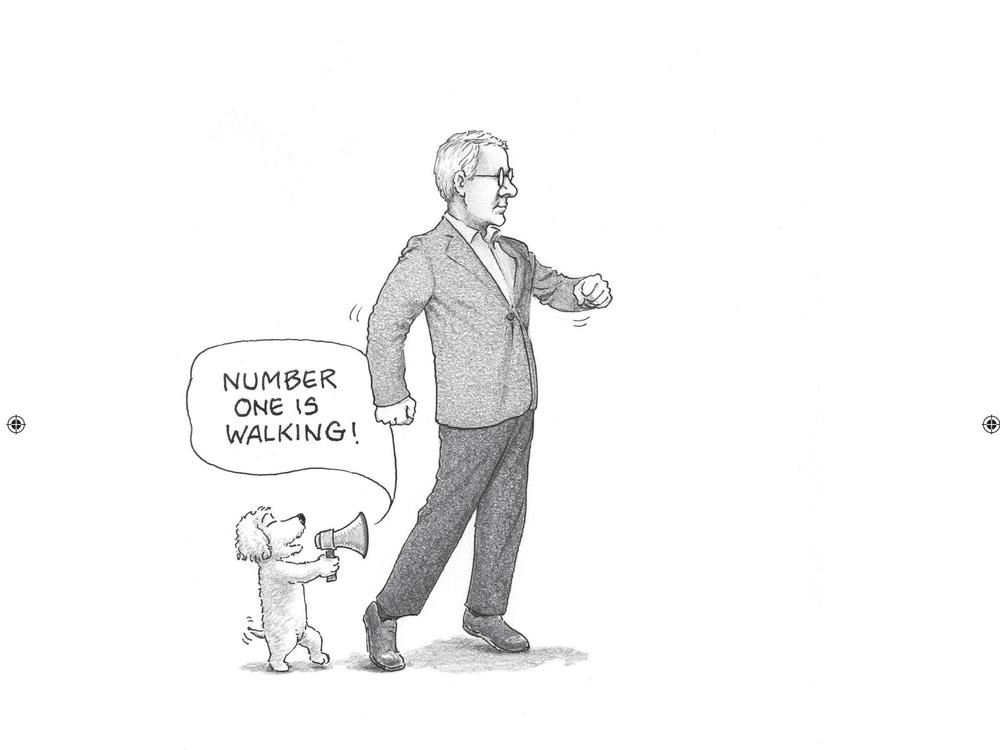

On the title, Number One is Walking

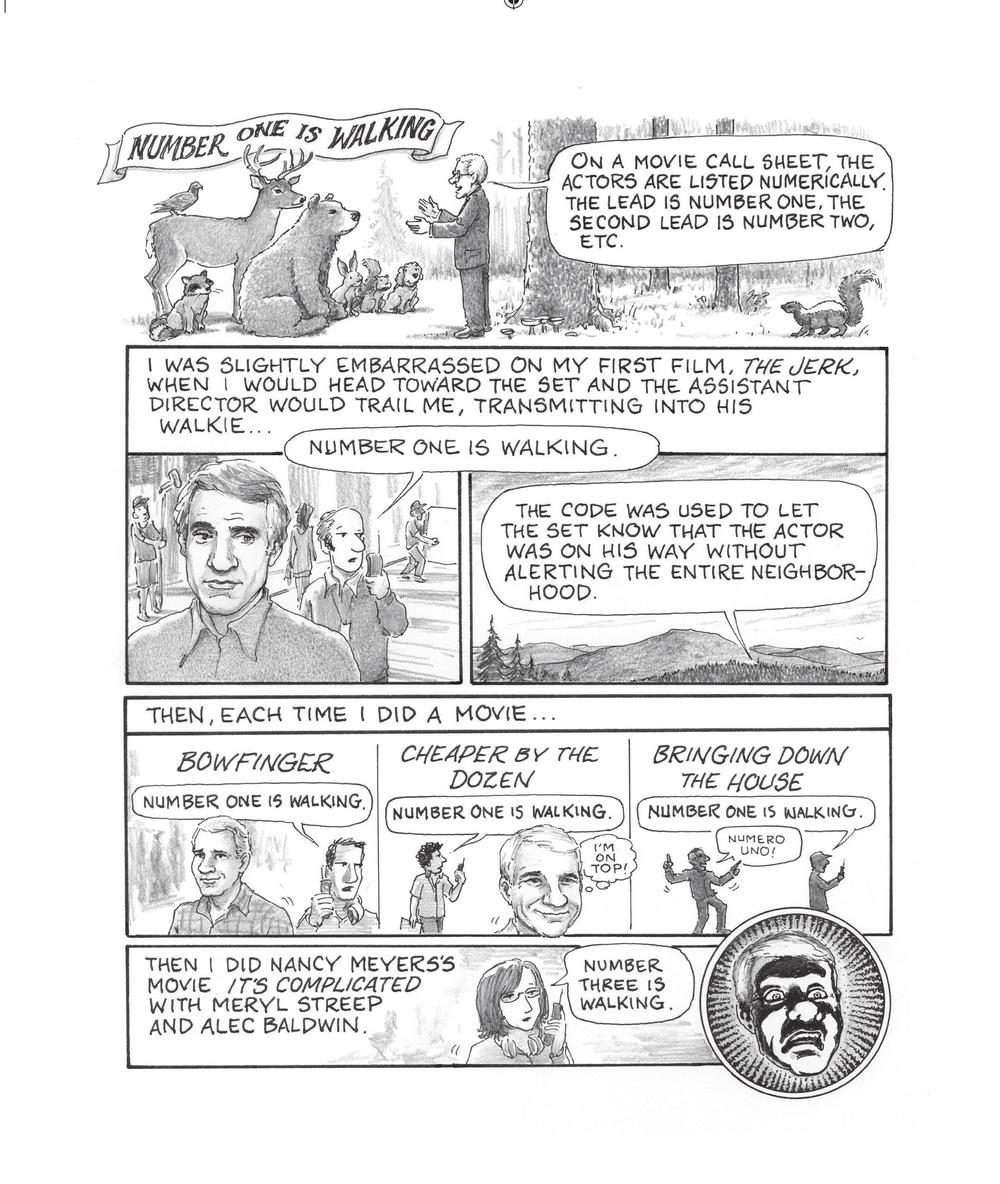

SM: Well, the original title is now the subtitle, My Life in the Movies and Other Diversions, which means there's cartoons, there's anecdotes and there's cartoons. But this phrase always stuck in my mind, "Number one is walking". It's used on a movie set when the call sheet comes in, the sort of lead actor, the ones with the most lines, is called number one. And then there's number two. And number three, the people that really buy lines.

And when the assistant director is on his walkie talkie, they don't want to say, "Steve Martin is walking to the set" because it can create a hubbub or something. So they changed it to, "Number one is walking, number two is walking." And it was always kind of embarrassing, you know.

On the process of creating the illustrations

HB: Well, the process, we sort of establish this a little bit in the first book that we did together. But I generally will start off, Steve, in this case, he's talking to some animals in the woods. There's a bear, and there's a deer, and a raccoon, and other animals. So he's telling this anecdote to these animals. Part of the reason I do this, open it this way, it's kind of an establishing shot, is that I love to draw animals and trees. It's just fun for me.

And I love the kind of incongruity of Steve in the woods. So he's talking to them. It's kind of a vignette of the image. From there, it's called "breakdown" in comics. So I'll break these panels down. I'll break down Steve's words, which come to me in an email.

He will write them out and I'll start breaking it down into the way a storyboard artist might do a film. Maybe like the third panel is a pull back shot and you just see the word balloon coming from the mountain top there. And it's fun for me because I get to draw these things and it's always fun to draw Steve, his face. I can draw Steve in my sleep at this point.

Martin on the vulnerability involved in a memoir

SM: I guess there's an assumption that at a certain point you're just supremely confident. And I don't think that's probably true for anybody. And so I did this movie Parenthood, and I went to watch it. I could tell it was playing great. And driving home, I thought, "Wow, everyone in this movie is fantastic except for me."

And I went home and I laid in bed, which is part of the story. And I'm just thinking it over and thinking it over. And I thought, "Wait a minute, they didn't hire seven fantastic actors and one lousy one. So I must be good, too." It's just the thing of watching yourself, because it's just you. Where if you write a book, at least you're separated from the end product.

It's distinct from you. But here it just actually is you. And so, you don't look at yourself from a distance, you're looking at yourself inside. I don't know how to describe it.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.