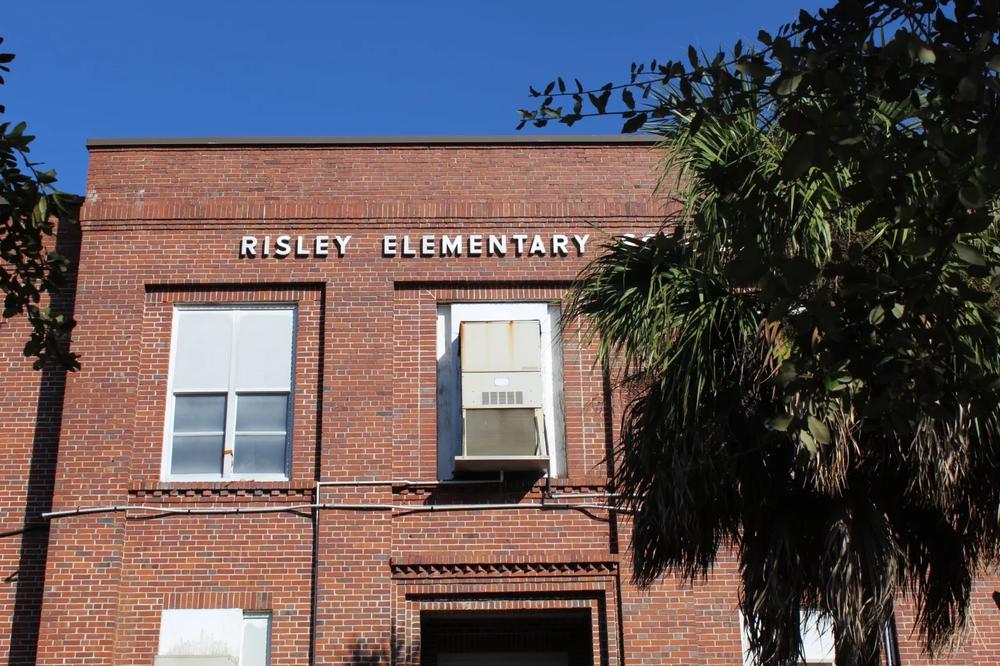

Caption

The historic Risley School in Brunswick off of Albany Street was the city’s first school for African Americans and opened in 1870. The school no longer educates children but may be the site of a future “justice center,” according to local advocates.

Credit: Erika Curtis / Georgia Justice Project