Section Branding

Header Content

Would-be Speaker McCarthy can learn from predecessors' struggles for the big gavel

Primary Content

The swearing in of a new Congress is now just a month away. Most of the top leadership positions for both parties in both chambers have been decided.

But one has not.

The Speaker of the House is the most powerful person on Capitol Hill and stands next after the vice president in the line of presidential succession.

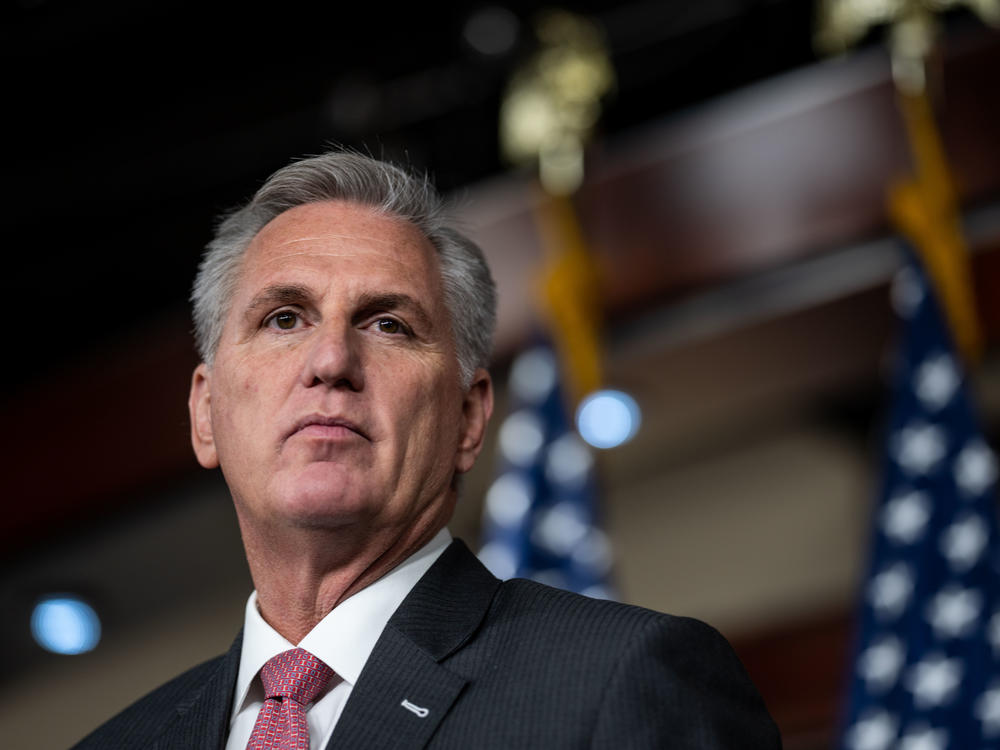

Kevin McCarthy of California is the Republican nominee for the job in the new, 118th Congress. But he first must win a majority of the whole House (or at least of those present and voting for a candidate) on January 3rd.

Most observers agree that McCarthy does yet not have the 218 votes it would appear he needs. Might he fall short? Can he win with fewer than 218? And how long can he run the House if he barely wins the right to do so?

We can look to history for help on all these questions. At a glance, the precedents suggest McCarthy will find a way to win on January 3rd. But at the same time, history suggests his prospects are far less promising when it comes to managing the majority and achieving its legislative and political goals.

The road to Gingrich's House GOP "revolution" was rocky

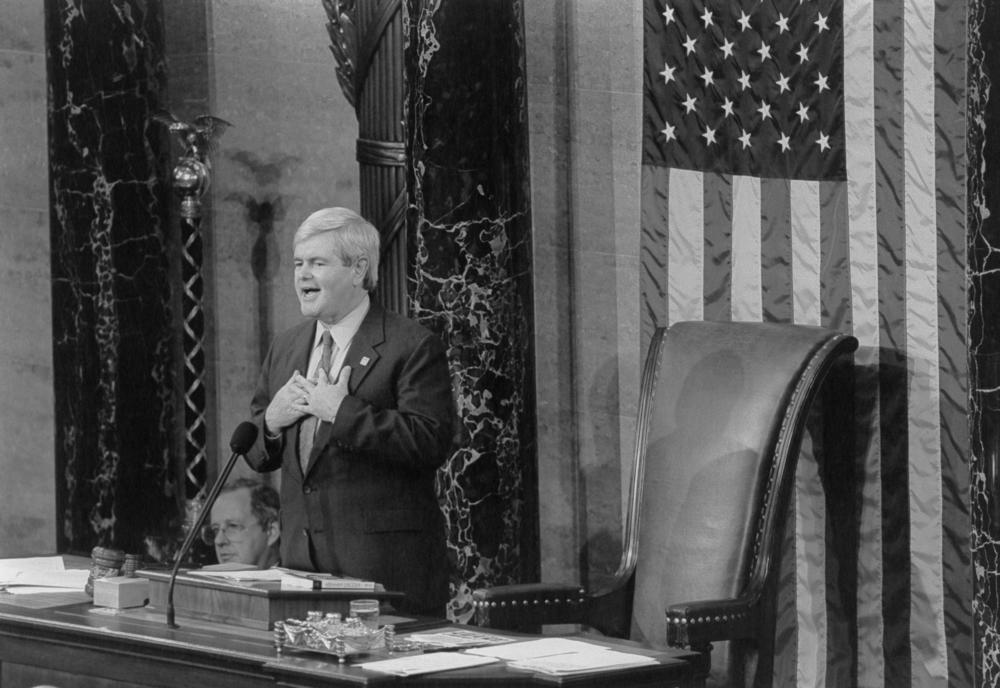

Being a Republican Speaker has often been challenging since Newt Gingrich of Georgia first grasped the big gavel in 1995. He was the first Republican to do so in 40 years, and some called the election that made it happen "the Gingrich revolution."

At that time, Gingrich ascended the House rostrum to cheers from his party ranks. Someone shouted "It's a whole Newt world."

But just two years later, reporters crowded into the House gallery with a far different air of anticipation. It was January 7, 1997, and the 1996 elections (in which President Bill Clinton won a second term) had cost Gingrich a few seats in the House, but his party still had 19 more seats than the Democrats. Gingrich's high-profile and adversarial leadership style had been alienating even when it was successful.

Most immediately on that January day, Gingrich was still battling a House Ethics Committee case regarding his unreported outside income. Several members of the Republican majority had bailed out, saying they would not vote for Gingrich again.

The most senior among them, Banking Committee Chairman James Leach of Iowa said: "Winning does not vindicate taking shortcuts with public ethics." (Leach apparently liked that summation well enough to use it again, verbatim, when he voted for the impeachment of President Bill Clinton in December 1998.)

But nearly two years earlier, when the question was Gingrich, Leach voted instead for a former member, Bob Michel of Illinois, the House Republican leader for 14 years before Gingrich displaced him. Two other Republicans cast their votes for Speaker for Leach, and a third voted for another former member. Five other Republicans who had declined to back Gingrich simply voted "present."

Bill Archer of Texas, the influential chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, had been non-committal in the weeks after the election. On the day before the vote, he indicated he would vote for Gingrich; but reporters in the gallery still leaned forward when the clerk called Archer's name.

"Gingrich," he responded, in a voice that conveyed neither doubt nor certainty.

Several members missed the vote entirely. In the end, Gingrich's 216 votes gave him a majority of the 425 who were present and named someone.

But it was a sobering moment for the man some had hailed as the GOP's Moses after he led the party out of 40 years in the wilderness of minority status. It foretold some of the problems he would have within his own party later in the 105th Congress.

Boehner learned that some in his ranks eschewed cooperation

Gingrich's eventual successor, Dennis Hastert of Illinois, won four terms as Speaker with narrow majority margins but minimal drama.

McCarthy may be especially envious of Hastert's election in January 2001, when the Republican majority in the House was down to just 221 seats (more or less exactly where McCarthy finds it today). Hastert breezed to a third term with the gavel without much fuss at all. But no Republican Speaker has been quite so fortunate since.

Hastert left Congress in 2007 and years later was sentenced to prison. The case involved money he paid in an attempt to cover up his sexual abuse of high-school aged boys when he was a wrestling coach in Illinois in the 1960s and 1970s.

The Republican Party had lost its House majority in 2006 but seized it back with a net gain of 63 seats in 2010, the first midterm in the presidency of Democrat Barack Obama. That surge elevated veteran Republican John Boehner of Ohio to the Speakership in January 2011. While not himself part of the "Tea Party" wave, Boehner was next on the leadership ladder, and he was nominated by his party unanimously.

Thereafter, Boehner worked hard at relationships both with Obama's White House and the Democratic majority in the Senate. Known for his affability and working-class origins, Boehner might have been the Republican best equipped for the political tasks he faced – which were much like those facing the new Speaker in 2023.

But cooperation was not what some in his own ranks wanted. Boehner was barely re-elected Speaker in 2013, after Obama had been re-elected president. A dozen Republicans refused to vote for him, but he had enough of a majority to survive with 220 votes.

Things had not improved much when Boehner again stood for re-election as Speaker in January 2015. While he had followed the dictates of his caucus and scuttled ambitious budget deals he might have done with Obama, a faction known as the House Freedom Caucus still organized him and held him to 216 votes.

In September of 2015, Boehner announced he was quitting in mid-session even as he was attempting to negotiate an agreement to keep the government running without a shutdown.

Boehner and Ryan struggled to wrangle the House Freedom Caucus

At that moment, Boehner's No. 2 was McCarthy, who had moved up to House Majority Leader earlier that same year and seemed likely to be his successor. But in an interview with Sean Hannity of Fox News, McCarthy seemed to suggest that his party's multiple hearings on an ambassador's death in Benghazi, Libya, had been intended to damage the political popularity of Hillary Clinton (who had been secretary of state at the time).

After that, Republicans began casting about for an alternative to McCarthy. The House Freedom Caucus declined to support him. A consensus formed for Way and Means Chairman Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, who had been the party's nominee for vice president in 2012.

Ryan was subsequently elected by the full House in October 2015 with 236 votes, an absolute majority of the members. Two years later he was re-elected with only member of the Republican majority dissenting.

But Ryan, like Boehner, found the constant battle with the Freedom Caucus to be more than he could handle. Discouraged, still just 48, he announced in the spring of 2018 he would not stand for re-election. That fall, his party lost control of the House and Pelosi returned as Speaker and served for the next four years.

Both Boehner and Ryan have since worked as lobbyists in Washington.

Although Ryan encountered far less resistance to his election as Speaker, he had found much the same difficulty in carrying out the job. It was a replay of what Gingrich had found in the job in the late 1990s.

"Litmus-test Republicans" made Gingrich's tenure tough

Even after he had survived the ethics flap in January 1997, Gingrich found his once-grateful troops were restless. He faced down an open rebellion at a meeting of his caucus in the spring and that same summer escaped an attempted coup from within his own leadership team. When he achieved a major budget deal with President Clinton, he was criticized for it within the party.

In 1998 the House's focus shifted in 1998 to a protracted battle over Clinton's impeachment, displeasing many swing voters. Clinton's Democrats wound up actually gaining seats in the midterms that November (the first such win for a sitting president in 66 years). Gingrich caught the blame for it and stepped down within days.

One of Gingrich's confidantes in that era was Kenneth Duberstein, a former White House chief of staff for President Ronald Reagan, who spoke at the time to The New York Times.

"There was no doubt in mind [Gingrich] had the votes to win the Speakership [again]," Duberstein said. "But I'm not sure he had the votes to govern."

By way of explanation, Duberstein said "litmus-test Republicans" who focused on single issues such as abortion, same-sex marriage or taxes made it impossible for anyone to be an effective Speaker.

"They were saying we want this and we want that and they were denying him the flexibility to be able to put a governing coalition together," Duberstein said.

Gingrich could see that his next term at the top would be even rockier than his first two, and he chose to fall on his sword instead. It was a bitter moment that Boehner and Ryan would also taste in the decade ahead.

Factions within the parties are, of course, as old as the parties themselves, which arose in the chamber more than 200 years ago. Intraparty wars have been especially virulent in eras of realignment within the electorate, or when substantial parts of the country have opposed a war – such as Vietnam or the First World War.

Speakership woes go back to "the last of the czars"

The last time the House could not find a first-ballot majority for a single candidate for Speaker was exactly 100 years ago in January 1923. Republicans had 225 seats but had just been rocked by a 75-seat loss in President Warren Harding's first midterm, which followed the wreckage of the Teapot Dome scandal and the House's own refusal to accept the results of the 1920 Census.

Blocking a consensus at that time was an internal group of self-described progressives with the GOP who wanted changes to various rules and procedures favored by the party's Old Guard.

In the 1923 round, it took nine ballots to consolidate a majority behind the man who had been the sitting Speaker, Frederick Gillett of Massachusetts. He alone was able to promise serious consideration of the desired reform package. But Gillett would soon be gone, trading the big gavel for a seat in the Senate two years later.

It was in some respects an echo of the rebellion among progressives (in both parties) that had ousted Republican Speaker Joe Cannon of Illinois (the "last of the czars") in 1910. Cannon had and abused absolute power over committee chairs and assignments, floor procedure and rules for debate. No one since has had comparable authority. The Cannon House Office Building, the first such Hill building to bear a name, is named for him. It stands as a monument both to the pre-eminence of the Speakership and the impermanence of power.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.