Section Branding

Header Content

California offshore wind promises a new gold rush while slashing emissions

Primary Content

Installation of enormous floating wind turbines needed to turn West Coast ocean gales into clean electricity remains years off, but results of a federal lease auction this month off California promised to kickstart a work boom on the state's northern and central coasts.

The farming of wind power from American waters will be crucial in efforts to slash emissions of heat-trapping pollution from fossil fuels and ensure reliable supplies of electricity. While offshore wind farms are plentiful abroad and onshore wind energy is common through the U.S., just a handful of offshore turbines have so far been installed with many more planned along the East, West and Gulf coasts and potentially off Hawaii.

The redevelopment of 80 acres of waterfront land in Humboldt County into a hub for offshore wind operators and their vessels is imminent following the auction. Similar work will be needed in Morro Bay, onshore from three planned clusters of wind turbines.

"The work starts now," said Jeff Hunerlach, a building trades union leader based in Humboldt County after energy companies and joint ventures committed a total of $757 million to develop five floating wind farms clustered into two swaths of open ocean off Humboldt and Morro Bay.

Unions representing electricians, laborers and other trades — groups that for decades were frequently at odds with the green movement — joined environmental groups in celebrating the lease auction's results.

"It's a brand new industry," said Hunerlach, district representative at Operating Engineers Local No. 3 and local leader of 16 affiliated locals representing a variety of trades laborers. "For Humboldt," Hunerlach said,"this means growing the middle class."

Substantial new waterfront infrastructure will be needed at Humboldt and Morro Bay to bring electricity from offshore wind turbines onto shore, where it will power homes, electric vehicles and industry.

At the Humboldt port, Hunerlach anticipates hundreds of union workers will be employed during construction, with additional permanent jobs once the facility is running. Statewide, he expects the number of jobs created to support the new industry will be in the "tens of thousands."

The wind farm development rights were secured by large energy companies already developing wind farms on the East Coast, where shallower waters allow for the use of traditional tower-based designs. Some of the winning bidders are transitioning or expanding from fossil fuel to clean energy production.

"On an overall basis for offshore wind, we see the U.S. market as one of the top one or two markets globally that we'll be investing in over the next decade and a half," said Sam Eaton, a U.S.-based executive at RWE, a German energy company founded more than a century ago that secured the rights to build one of the wind farms off Northern California.

Other winning bidders included the wind division of Equinor, another energy giant expanding out of Europe, and several joint ventures created to deploy floating wind farms off the West Coast.

"When we focused in on the floating offshore wind space, California's option really put the U.S. right at the forefront," Eaton said. "It's one of the first to hit the kind of scale that we're talking about and sets up the Western part of the country extremely well to be a hub for the industry globally."

Best wind potential

While offshore wind power is a significant component of energy industries in Europe and Asia, just a handful of turbines are currently generating power in the U.S.

A belated offshore wind farming boom along the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf coasts is anticipated in the years and decades ahead, aided by international technology and know-how. Offshore wind energy is also being considered for Hawaii.

Offshore wind farming off the West Coast is complicated by the closeness to shore of the steep continental shelf. Waters viable for wind farming are too deep for the towers that hold most offshore turbines in place worldwide. The wind farms off California will be among the first in the world that float on giant platforms tethered to the seafloor and connected to land through electrical cables.

Efforts to build out the new industry will create jobs while providing federal incentives for developers to invest in coastal communities where new infrastructure will be needed. The efforts are however creating clashes with fishing fleets fretful not only of losing hunting grounds, but of broader impacts on their quarry from the new approach to renewables generation.

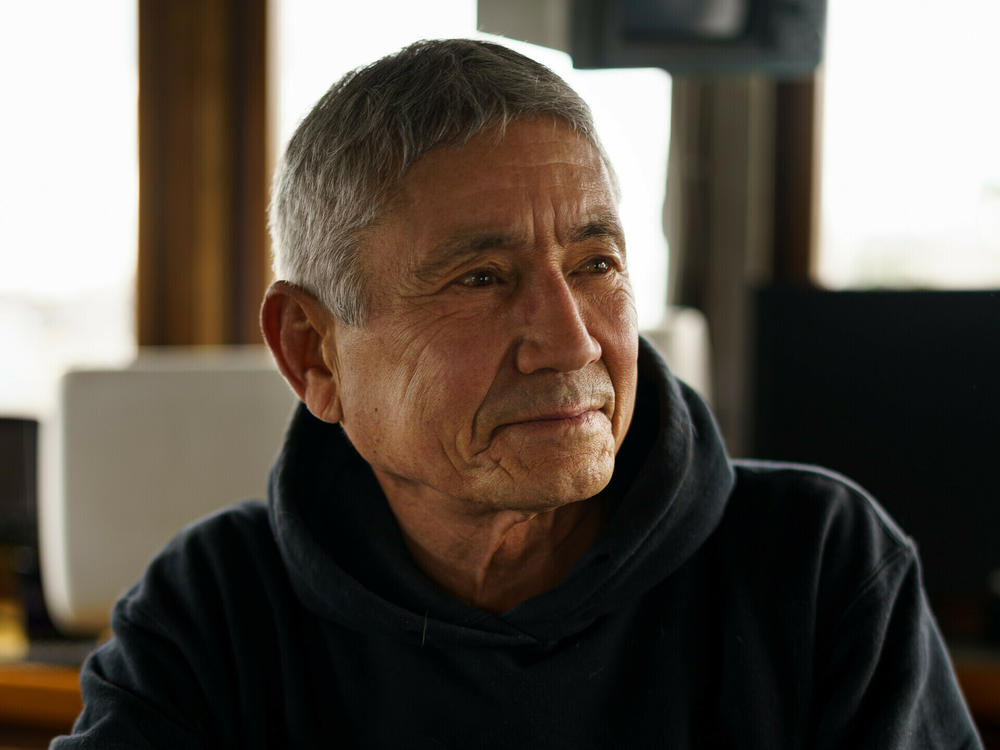

"We're going to throw billions of dollars into something that we don't really know what the impact is going to be," said Dick Ogg, a commercial fisherman of crab, albacore, black cod and rockfish. He's based out of Bodega Bay but he chases salmon from the state's north coast south to Morro Bay, which is another quiet part of California where an infrastructure boom is planned to get electricity from offshore wind turbines to land-based power customers. "We'd like to see a project that is smaller," said Ogg.

Fishing fleets nationally are angry about what they say is a lack of consultation with them by wind developers and by the federal government, with hundreds of lobstermen in Maine attending protests about plans there. Tribes, too, say their members are being ignored.

"We're asking developers to simply view us for what we are: sovereign nations," said Frankie Myers, vice-chair of the Yurok Tribe. The Yurok have lived in the redwood coast and along the Klamath River in what is now Northwestern California for thousands of years.

Yurok tribal leaders spoke with half a dozen potential developers in advance of California's offshore wind auction, but Myers said they weren't consulted by RWE or the other auction winners.

Myers said the worst impacts would be visual impacts from sacred high country, particularly at night during ceremonies that include prayers. He said the tribe also worries about unknown effects of rapid development in what has long been a quiet region.

"The last thing we want to do is destroy the environment in the process of trying to save it," Myers said. "This gung ho approach of having a single-minded goal is exactly how that happens. We have to look at this. We have to weigh every step. That's what we do as tribal people."

RWE's Eaton said the company had held off on engaging with groups like fishing fleets and tribes in California until it had won a lease at auction. "We're prepared to begin those dialogues very soon," said Eaton.

Wind's role in reducing carbon emissions

Researchers at Princeton University modeled a variety of pathways that could see the U.S. reach net carbon neutrality by 2050, meaning the nation would stop being a net climate polluter by that point. Without offshore wind, it would technically be possible to reach 'net zero' by 2050, but that would be "more expensive than tapping into the abundant strong wind potential that's right off our shores," said Jesse Jenkins, a member of Princeton's Net Zero America project.

"The best wind potential in the country, if not the world, is off the Northern California and Southern Oregon coast," Jenkins said. "It's an important resource that the region is looking to tap into."

The Net Zero America project didn't consider potential wave energy generation because it isn't yet commercially viable. But Jenkins said the heavy chop of the Pacific Ocean could eventually be used to produce this additional form of clean ocean energy — perhaps operating off the same floating platforms as wind turbines.

"There are several companies working to develop wave energy," Jenkins said. "It's very difficult to build things that can survive the pummeling of West Coast waves."

A cornerstone of ambitious plans

State renewable energy mandates in California and elsewhere have for years spurred planning of offshore wind farming, with the goal of replacing power plants that generate the pollution responsible for climate change. More recently the federal government under President Joe Biden has been working to open additional offshore waters for potential leases and to eliminate development bottlenecks imposed by the pro-fossil fuel Trump administration.

California air regulators have charted an ambitious path to dramatically reducing planet-warming emissions over the next two decades, which Gov. Gavin Newsom has said will "spur an economic transformation akin to the industrial revolution" and create a "pollution-free future."

To hit clean energy targets that are among the most ambitious in the world, California will have to foster the construction of renewable generating capacity faster than ever before. The state is relying on robust offshore wind development in this plan. It wants to see 5 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity installed by 2030, which would be roughly equivalent to the output of 8 or 10 natural gas power plants. The goal quadruples by 2045.

California is working to overcome workforce and technological barriers that could hinder the new industry, and it's banking on rapid global innovation to push wind farms into deeper waters.

"Floating platforms are going through a period of great innovation," said Stephanie McClellan, executive director of the recently formed nonprofit Turn Forward, which aims to accelerate the buildout of offshore wind farms nationally. Gas-and-oil drillers already use floating turbines, and some of those designs are being adapted for wind farming.

"We're starting to see a variety of different innovations, a number of different designs," McClellan said. "We'll start to see which of these are going to rise to the top in terms of usage."

While floating technology is essential for building wind turbines along California's coast, it could turn out to be superior to the fixed-tower turbines that currently dominate the industry.

That's because building further offshore, where floating technology would be required even along the East Coast and along other shallower coastlines, reaches stronger winds while reducing potential conflicts with fishing fleets. It can also ease concerns of residents and tourism operators about impacts of wind farms on ocean views. "There's higher wind speeds in deeper waters," said McLellan.

Some environmental risks, many benefits

Assessing the likely environmental impacts of floating wind generation is difficult "because there's not an awful lot of it in the world," said Andrea Copping, an oceanographer at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. After spending a decade investigating likely impacts, she said "the risks are reasonably small and manageable."

Because the turbines will be so far out to sea, there would be fewer threats of turbine blades striking land-based birds and bats, Copping said. Tethering platforms to the seafloor should also cause fewer harms than the installation of towers, which require extensive pile driving that can harm whales and other wildlife by creating underwater booms.

"The more platforms you put out there, you increase the risk incrementally with each one," Copping said. "If I have concerns at all, it's probably looking 30 or 40 years in the future with many, many things out there."

Impacts aside, some environmentalists are leery at the presence of fossil fuel companies in the growing offshore wind sector.

Shell is a joint-venture partner on a wind farm planned off the coast of New Jersey, which is leading efforts on the East Coast to attract offshore wind farm manufacturing and other facilities to its shores. Other gas and oil giants like BP registered to bid at the auction, which closed on Dec. 7, though none emerged as winners.

Jeff Tittel, a veteran New Jersey environmentalist and former president of the state's Sierra Club chapter, points out that many of the wind developers setting up operations in the U.S. retain extensive fossil fuel operations, which he says erodes trust. RWE, for example, operates natural gas-fired power plants across Western Europe. Equinor traces its roots back 50 years when it was founded as the Norwegian State Oil Company, Statoil, and it remains a fossil fuel giant.

"I kind of get it, that energy companies want to diversify, like they used to be coal, and then they went into oil and then they went into wind and solar," Tittel said. "Does that mean that they're willing to go to one hundred percent renewable and put their other businesses out of business? That's why I say there's a trust issue."

For unions, working for fossil fuel companies is nothing new. What's new for them are vast workforce opportunities in a fast-emerging industry — one that's slowing the destruction of a livable climate, instead of contributing to it.

"This is a climate change issue," said Hunerlach, the union official in Humboldt County. "We're really excited to be able to be part of this historic new industry."

This story was produced through a collaboration between KQED in California and Climate Central.

Copyright 2022 KQED. To see more, visit KQED.