Caption

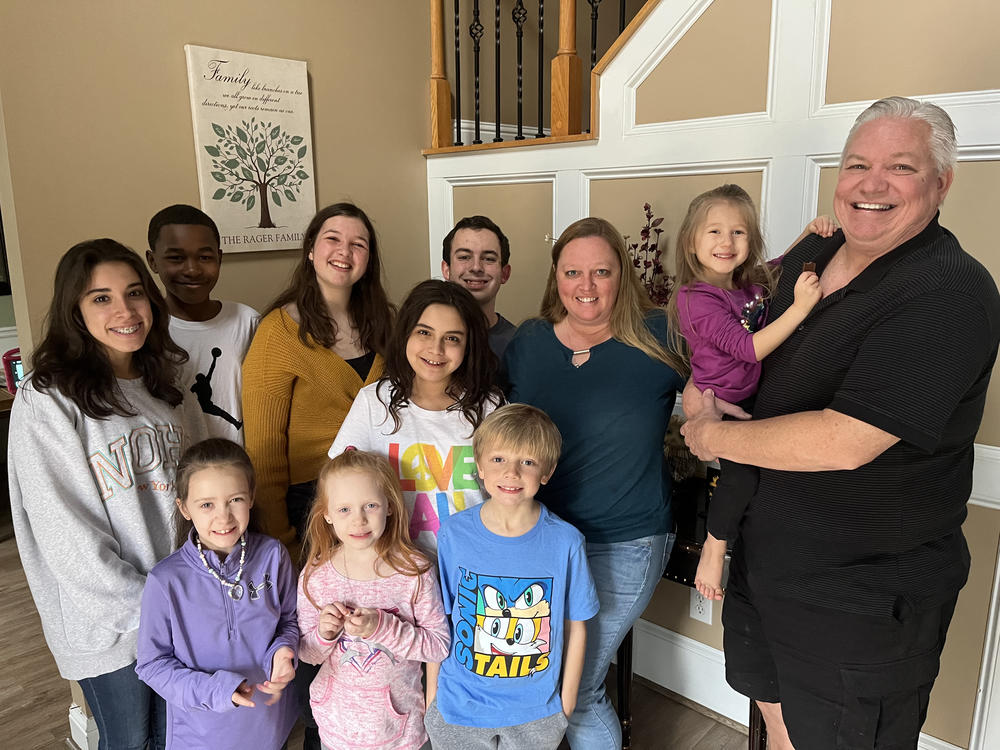

Lisa Rager knows well the hurdles to obtaining services for foster kids. She and her husband, Wes, have cared for more than 100 foster children and adopted 11 of them, many of whom are pictured. Rager says one child waited more than a year for an appointment to see a specialist doctor.

Credit: Andy Miller/KHN