Caption

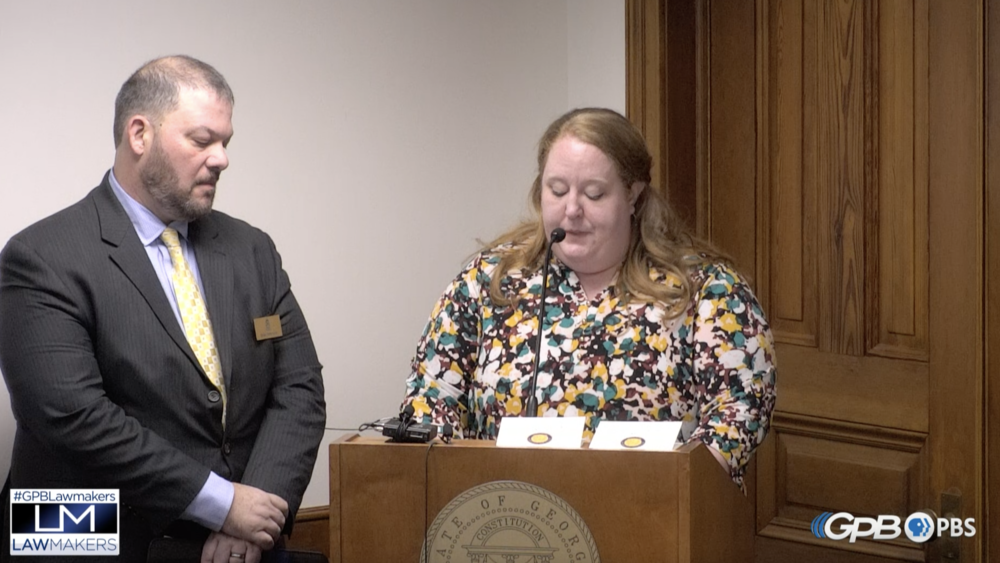

At Wednesday’s joint Senate Health, Human Services, Children, & Families Committee meeting, Aubrey Brannen, from the Department of Family & Children Services, pleaded for Senators' help with the "hoteling" issue around the state.

Credit: GPB Lawmakers