Caption

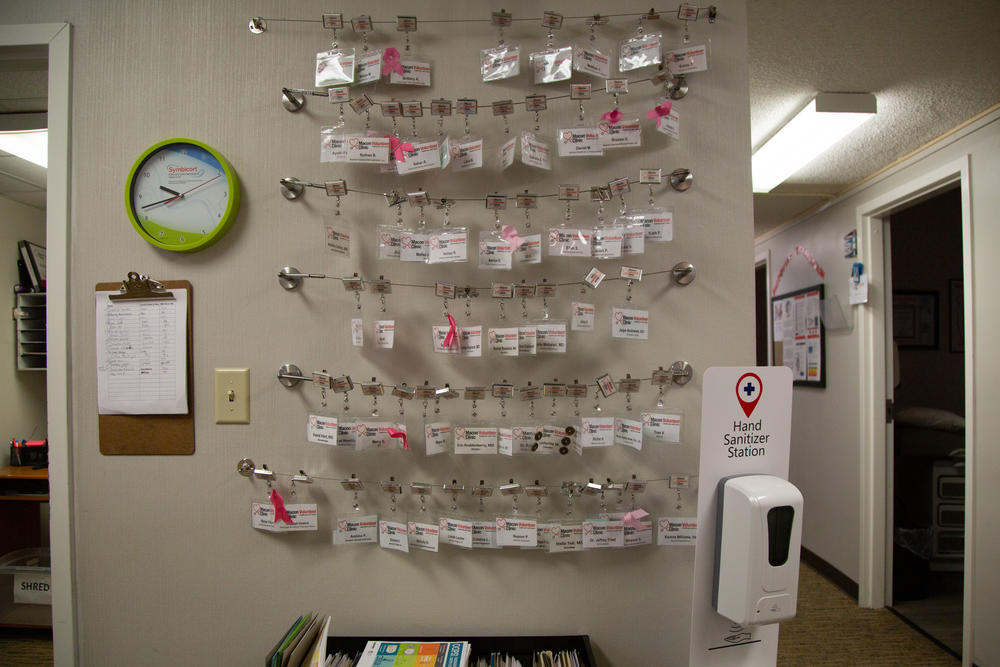

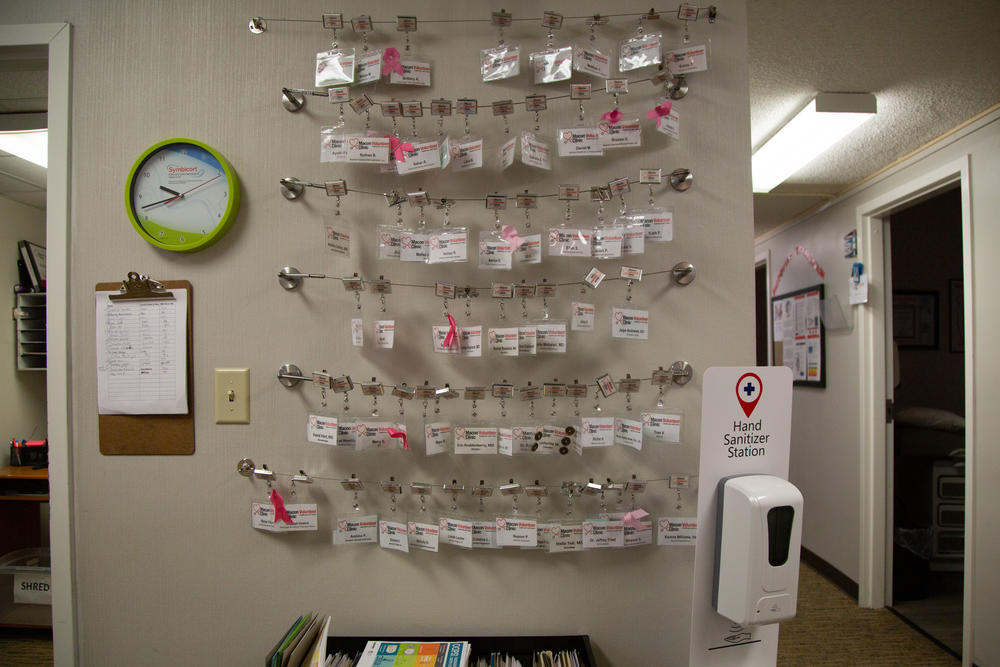

Volunteer name tags at the Macon Volunteer Clinic. The clinic relies on volunteer physicians to provide free care to working, low-income people who don't qualify for insurance.

Credit: Sofi Gratas / GPB News

On a Monday afternoon at the Macon Volunteer Clinic, doctors, nurses and administrators in the back assist patients.

The clinic relies on volunteers to provide free medical services to working, low-income patients who don’t qualify for health insurance.

Dr. Patrick Roche has been volunteering at the clinic since it opened 20 years ago.

“Most of the people that we see come from local restaurants, dry cleaners, gas stations, small businesses that don't have to insure them,” Roche said.

They’d all be considered essential workers. Roche says some of his patients even work for doctors.

In addition to not having access to benefits, they often make too much to qualify for Medicaid, but too little to afford average premiums for marketplace insurance.

That puts them in a coverage gap.

Volunteer name tags at the Macon Volunteer Clinic. The clinic relies on volunteer physicians to provide free care to working, low-income people who don't qualify for insurance.

“So they fall through the cracks,” said Nancy White, executive director at the clinic.

White said clinic patients can make no more than $29,000 a year, or 200% of the federal poverty level.

“So they are very challenged, but they're working,” White said.

And working matters for Georgia’s planned Medicaid expansion, which will extend Medicaid to thousands of low-income, uninsured adults.

After years of litigation with the federal government, Georgia was left with a choice: full Medicaid expansion the federal way, or an alternative plan from the state.

Unlike a full Medicaid expansion, the state’s program will have its own set of rules that may limit who can actually take advantage of the new access the program provides.

The program, called “Pathways to Coverage,” will go live in July. Some of Georgia’s 1.2 million uninsured adults will be eligible for Medicaid, but only if, like the patients at the Volunteer Clinic, they work.

People between 19 and 64 years old will qualify for the plan only if they complete 80 hours a month of certain activities, including work, but also community service or higher education.

Those who already qualify for Medicaid, including pregnant people and people with certain disabilities, will not be affected by the new requirements.

The state’s idea, as described in the language of the program itself is to create “incentive for participation in work and other employment-related activities for those not currently engaged”

Laura Colbert is Executive Director of Georgians for a Healthy Future. She has doubts.

“The evidence is very nonexistent that the work requirement would motivate somebody to kind of go out and get a job when they wouldn't otherwise,” Colbert said.

Why, she asks, would health insurance be a stronger incentive to work than basics like food and shelter?

“Medicaid will not pay your rent, your utility bill or put gas in your car,” Colbert said. “And, you know, it's not like people get a check for Medicaid. All they get is health care.”

But more importantly, Colbert said that while Pathways will expand coverage, it doesn’t include everyone that needs it.

That’s because lots of people simply can’t work.

“Not only are people with serious mental illness and full-time caregivers going to be left out,” Colbert said, “but there will also be some groups that are disproportionately left behind by the program.”

Like those in rural areas where there aren’t good-paying jobs, or some minorities living in historically disinvested communities, she said.

Some critics of the plan say it should instead mirror work requirements under SNAP, or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. SNAP includes work exemptions for people over 60 years old, those who have physical or mental disabilities and people who care for a child younger than 7 years old, among others.

A 2022 estimate from the Kaiser Family Foundation puts 269,000 adults in Georgia in the health insurance coverage gap. The same report says over half of Medicaid recipients are already working, though they may not be working 80 hours a month.

Regardless, administrative hurdles may make turning on work requirements difficult for some, Colbert says.

“If you're a person without a house, you know, you're probably not going to go to your local DFACS office every month and make sure that they know that you're still homeless in order to get coverage and the exemption.” Colbert said.

According to language in the waiver, the program will offer some exemptions to the work requirements, but only temporarily for serious life events, such as illness or the death of a family member.

Those likely left behind by the program will even include some patients at the Macon Volunteer Clinic, who are already working but still struggle financially.

To qualify for Pathways, people can only make up to $15,000 a year, or 100% of the federal poverty level. At the volunteer clinic, the cutoff for a patient is $29,000, or 200%.

So many who are seen at the free clinic will remain uninsured. Plus, Roche said the care he and other primary care physicians at the clinic can provide his patients has limits.

“Perhaps someone has gallbladder disease and they need to have gallbladder surgery,” Roche said. “But until their gallbladder gets infected and they become septic and have to go to the emergency room, they can't afford that procedure.”

Carl Lane is a retired cardiothoracic surgeon who has volunteered at the Macon Volunteer Clinic for 11 years. He says often, his patients arrive at the clinic without having seen a doctor for years.

“So we do our best to try to get them back on track and fix them up best we can,” Lane said.

In communities without free or low-cost clinics, emergency rooms will likely remain the place for primary care. Medicaid cost reports show hospital uncompensated care costs in 2018 were almost double in states that didn’t fully expand Medicaid, compared to those that did.

But some Republican lawmakers in Georgia argue that because so few providers even accept Medicaid for its low reimbursement rate, expanding the program could be more expensive for providers.

“Instead of expanding a broken system, we are taking practical steps towards improved coverage and access statewide,” Gov. Brian Kemp said in a tweet accompanying the program's intended launch date.

Georgia is one of 11 states that has not fully expanded Medicaid. Come July, it will be the only state with a work requirement in place.

Nancy White, director of the Macon Volunteer Clinic, said she “100%” supports any program that can make a dent in covering the uninsured population.

But she wonders if Pathways may leave more questions for lawmakers.

“Are we going to need another kind of safety net or are we going to need to change our eligibility criteria for those people that can't meet the work requirement and they are left with nothing?” White said. “That's a great concern.”

Georgia’s Department of Community Health estimates more than a quarter million people will be eligible for Pathways to Coverage this summer. Meanwhile, nearly 900,000 people will remain uninsured.