Section Branding

Header Content

A skinny robot documents the forces eroding a massive Antarctic glacier

Primary Content

Scientists got their first up-close look at what's eating away part of Antarctica's Thwaites ice shelf, nicknamed the Doomsday Glacier because of its massive melt and sea rise potential, and it's both good and bad news.

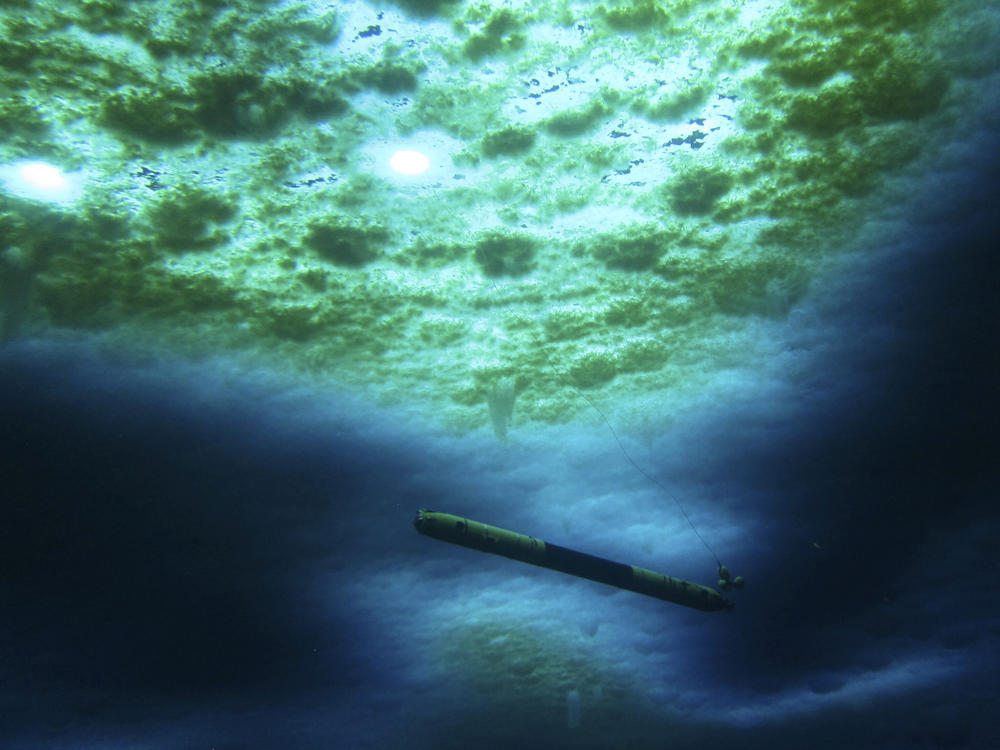

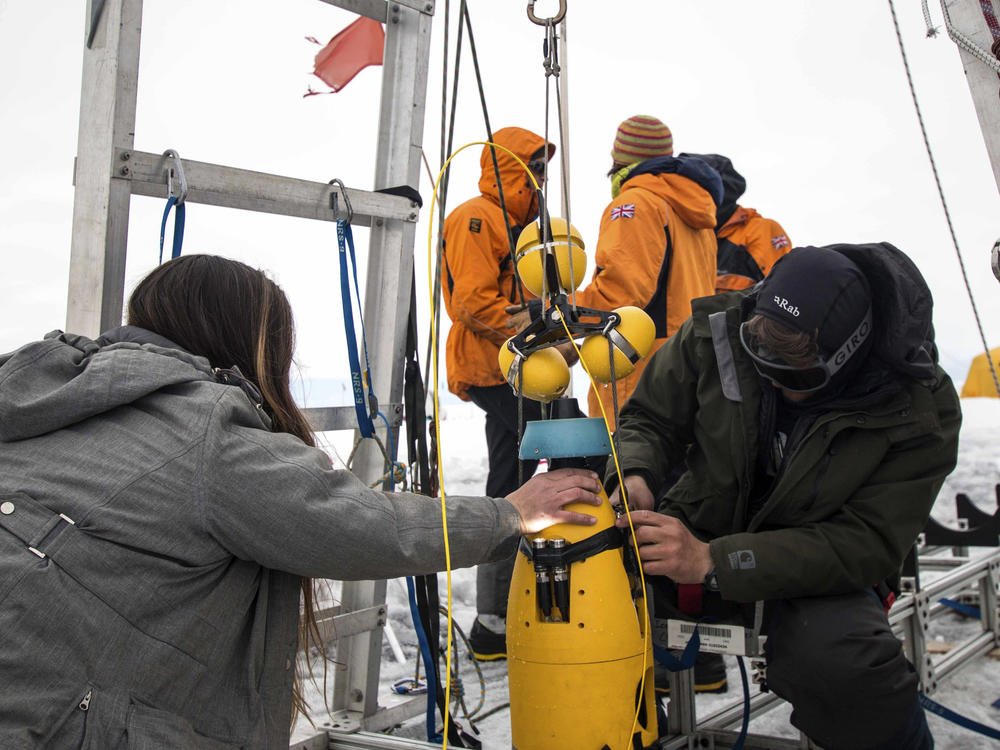

Using a 13-foot pencil-shaped robot that swam under the grounding line where ice first juts over the sea, scientists saw a shimmery critical point in Thwaites' chaotic breakup, "where it's melting so quickly there, there's just material streaming out of the glacier," said robot creator and polar scientist Britney Schmidt of Cornell University.

Before, scientists had no observations from this critical but hard-to-reach point on Thwaites. But with the robot named Icefin lowered down a slender 1,925-foot (587-meter) hole, they saw how important crevasses are in the fracturing of the ice, which takes the heaviest toll on the glacier, even more than melting. "That's how the glacier is falling apart. It's not thinning and going away. It shatters," said Schmidt, lead author of one of two studies in Wednesday's journal Nature.

That fracturing "potentially accelerates the overall demise of that ice shelf," said Paul Cutler, the Thwaites program director for the National Science Foundation who returned from the ice last week. "It's eventual mode of failure may be through falling apart."

The work comes out of a massive $50 million multi-year international research effort to better understand the widest glacier in the world. The Florida-sized glacier has gotten the nickname the "Doomsday Glacier" because of how much ice it has and how much seas could rise if it all melts — more than 2 feet (65 centimeters), though that's expected take hundreds of years.

The melting of Thwaites is dominated by what's happening underneath, where warmer water nibbles at the bottom, something called basal melting, said Peter Davis, an oceanographer at British Antarctic Survey who is a lead author of one of the studies.

"Thwaites is a rapidly changing system, much more rapidly changing than when we started this work five years ago and even since we were in the field three years ago," said Oregon State University ice researcher Erin Pettit, who wasn't part of either study. "I am definitely expecting the rapid change to continue and accelerate over the next few years."

Pennsylvania State University glaciologist Richard Alley, who also wasn't part of the studies, said the new work "gives us an important look at processes affecting the crevasses that might eventually break and cause loss of much of the ice shelf."

The good news: Much of the flat underwater area they explored is melting much slower than they expected. The bad news: That doesn't really change how much ice is coming off the land part of the glacier and driving up sea levels, Davis said.

Davis said the melting isn't nearly the problem at Thwaites that glacier retreat is. The more the glacier breaks up or retreats, the more ice floats in water. When ice is on ground as part of the glacier it isn't part of sea rise, but when it breaks off land and then goes onto water it adds to the overall water level by displacement, just as ice added to a glass of water raises water level.

And more bad news: This is from the eastern, larger and more stable part of Thwaites. Researchers couldn't safely land a plane and drill a hole in the ice in the main trunk, which is breaking up much faster. And they also found staircase-like steps, those crevasses, in parts of the more stable eastern side where the break-up is far faster and worse.

The key to seeing exactly how bad conditions are on the glacier would require going to the main trunk and looking at the melting from below. But that would require a helicopter to land on the ice instead of a heavier airplane and would be incredibly difficult, said studies co-author Eric Rignot of the University of California Irvine.

The main trunk's glacier surface "is so messed up by crevasses it looks like a set of sugar cubes almost. There's no place to land a plane," NSF's Cutler said.

Ted Scambos of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, who wasn't part of the studies, said the results add to understanding how Thwaites is diminishing.

"Unfortunately, this is still going to be a major issue a century from now," Scambos said in an email. "But our better understanding gives us some time to take action to slow the pace of sea level rise."

When the skinny robot wended its way through the hole in the ice – made by a jet of hot water – the cameras showed not just the melting water, the crucial crevasses and seabed. It showed critters, especially sea anemones, swimming under the ice.

"To accidentally find them here in this environment was really, really cool," Schmidt said in an interview. "We were so tired that you kind of wonder like, 'am I really seeing what I'm seeing?' You know because there are these little creepy alien guys (the anemones) hanging out on the ice-ocean interface.

"In the background is like all these sparkling stars that are like rocks and sediment and things that were picked up from the glacier," Schmidt said. "And then the anemones. It's really kind of a wild experience."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.