Caption

In Georgia and nationwide, nighttime temperatures have been growing warmer across the decades.

Credit: Photo courtesy of Carlos Rosemberg via stock.xchng

LISTEN: GPB's Peter Biello speaks with Climate Central meteorologist Lauren Casey about the impact of warming winters.

In Georgia and nationwide, nighttime temperatures have been growing warmer across the decades.

Warming temperatures across the U.S. have meant fewer nights when the temperature drops below freezing. Climate scientists expect this trend to continue. According to meteorologists at the nonprofit Climate Central, assuming a moderate amount of carbon emissions, Georgia is expected to have about nine fewer freezing nights per year on average. For a look at what this means, GPB's Peter Biello spoke with Climate Central meteorologist Lauren Casey.

Peter Biello: So from your research and existing data, what did Georgia look like 50 years ago from a weather standpoint, particularly winter weather and freezing weather?

Lauren Casey: Due to human-driven climate change, we're seeing warming in all seasons all across the country, including in Georgia. And winter is the fastest-warming season in most locations and regions. Now, this has myriad impacts on wildlife, ecosystem health, human health and wellness, as well as recreation. So we're seeing warming in the daytime, but we're especially seeing warming in the overnight periods. So we're seeing far fewer nights below freezing.

Peter Biello: In your analysis, how did Atlanta fare?

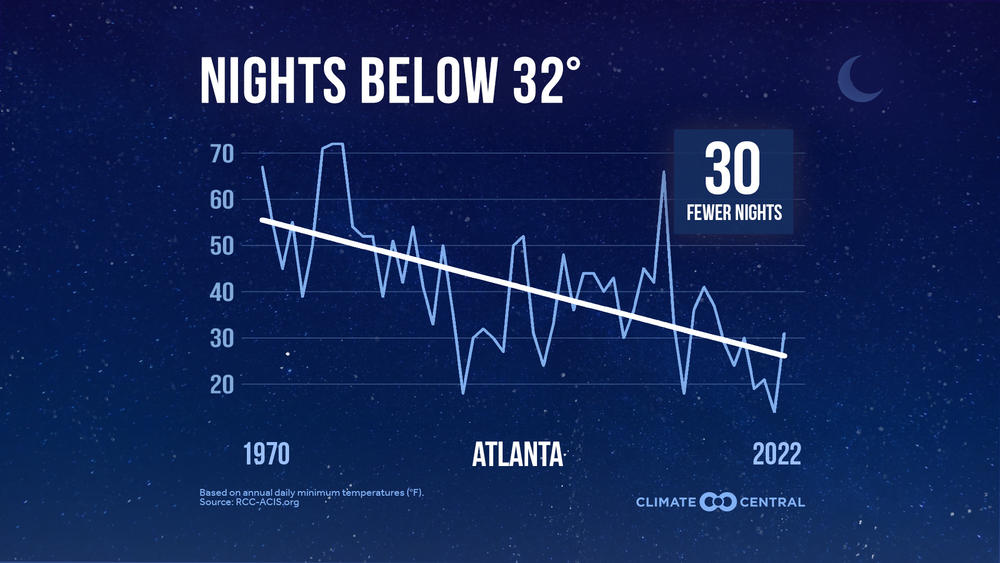

Climatecentral.org finds Atlanta has an average of 30 fewer freezing nights now compared to 1970.

Lauren Casey: Yeah, the number for Atlanta is quite astounding. Since 1970, Atlanta now experiences, on average, 30 fewer nights below freezing in the wintertime season. All across the state of Georgia, your average wintertime temperature has increased by at least 3 degrees for all locations. You take a look at Atlanta, though, that figure increases to nearly 6 degrees.

Peter Biello: Is there a difference felt between urban areas and rural areas when it comes to the impact of having fewer freezing nights?

Lauren Casey: Absolutely. In urban areas, we see warmth that is exacerbated by the urban heat island effect. So you have all the buildings, all the impervious surfaces, all the asphalt, the concrete, the sidewalks. It retains that warmth, particularly at night and then rereleases it. So those temperatures stay warmer, typically, in an urban environment than they would [in a] rural environment.

Peter Biello: What about pollen? I've heard, anecdotally, from friends and coworkers who've lived in Georgia for a while who say that the pollen right now seems to be out in full force much earlier in the year than usual. What's what's your take?

Lauren Casey: Yeah, it's really quite incredible. We're seeing blooms already. Already! ...And in Georgia right now, you're experiencing those spring blooms two to three weeks earlier than average. Two to three weeks! So we're already dealing with the pollen from the flowering trees and plants.

Peter Biello: And what impact does that have on agriculture?

Lauren Casey: That has a huge implication for agriculture as well, because especially if you go backwards a little bit for wintertime and of particular concern in Georgia, of course, known for its peaches, we're seeing in a reduction of something called chill hours or cumulative hours with temperatures generally between freezing and 45 degrees, that fruiting trees need to kind of rest or essentially chill in order to produce the best crop yields in the spring and summertime. Now, if this process is compromised with these warmer overnight periods, this can have profound economic consequences for local and regional economies. Now, 84% of locations analyzed by Climate Central have experienced decreases in these chill hours since 1980.

Peter Biello: Who ultimately is most affected by the reduction in nights where the temperature drops below freezing?

Lauren Casey: Most impacted would be potentially rural communities, farmers, people who depend on crops for their livelihoods.

Peter Biello: Let's talk solutions. What can be done to alleviate the worst impacts of having fewer freezing nights?

Lauren Casey: It's a great question. Well, No. 1 is we need to reduce our dependence on carbon so we can stop this planetary warming and all of its local and regional impacts that we're seeing across the board that we really need to invest in adaptation and mitigation and move the conversation more towards solutions. So especially investing in solar and wind energy and alleviating that dependence on carbon.