@_navalny_ Шутки шутками, но если зайдёте на мой ютюб-канал, то посмотрите потрясающее расследование. Дело раскрыто #howbizarre #navalny #poisoning #novichok ♬ How Bizarre - OMC

Section Branding

Header Content

'Navalny' director says Russian opposition leader's spirit is unbroken

Heard on

Primary Content

Director Daniel Roher first thought about making Alexei Navalny the subject of his latest documentary, when he was in Vienna, Austria, with Christo Grosev, an investigative journalist.

Navalany began his presidential campaign against the Kremlin in 2016. The campaign didn't lead to Navalny securing the executive chair, but he continued to organize nationwide "anti-Putin" protests. On Aug. 20, 2020, Navalany was poisoned with Novichok, a chemical that disrupts the ability of nerves to send messages to organs. Russia has never confirmed the nerve agent exists.

Grosev, a Russia investigator with Bellingcat, was investigating who poisoned the opposition leader, and Roher said Grosev informed him he might have a lead on the culprit.

A week later, in November 2020, Roher went with Grosev to meet Navalny in Germany, where he was staying to recover from the poisoning. It was there that Roher said he made an "emotional pitch" to Navalny about a documentary on his recovery and eventual return to Russia.

"Here's a guy who needs no help getting his message out to the world. He has a gigantic media presence, essentially social media companies, the YouTube channel that reaches hundreds of millions of people," Roher told NPR.

"Why then does he need a film? And that's what I had to convince him of, and that's what I had to enlighten him towards."

Navalny wasn't buying it, Roher said. So, he tried again.

"The other thing I told him is that if we don't start filming now, you'll never get it again, what's happening is happening in real time, we should start immediately."

Roher is not unfamiliar with sparking up conversation in uncanny settings. NPR's Steve Inskeep spoke to Roher about "Navalny" — which won "best documentary" at this year's BAFTA — while he was in a decommissioned refrigerator at the Ritz Theater in Elizabeth, New Jersey. He was on the set of his wife Caroline Lindy's upcoming film.

"It's the quietest place I could find," Roher said. "But you might hear stuff outside."

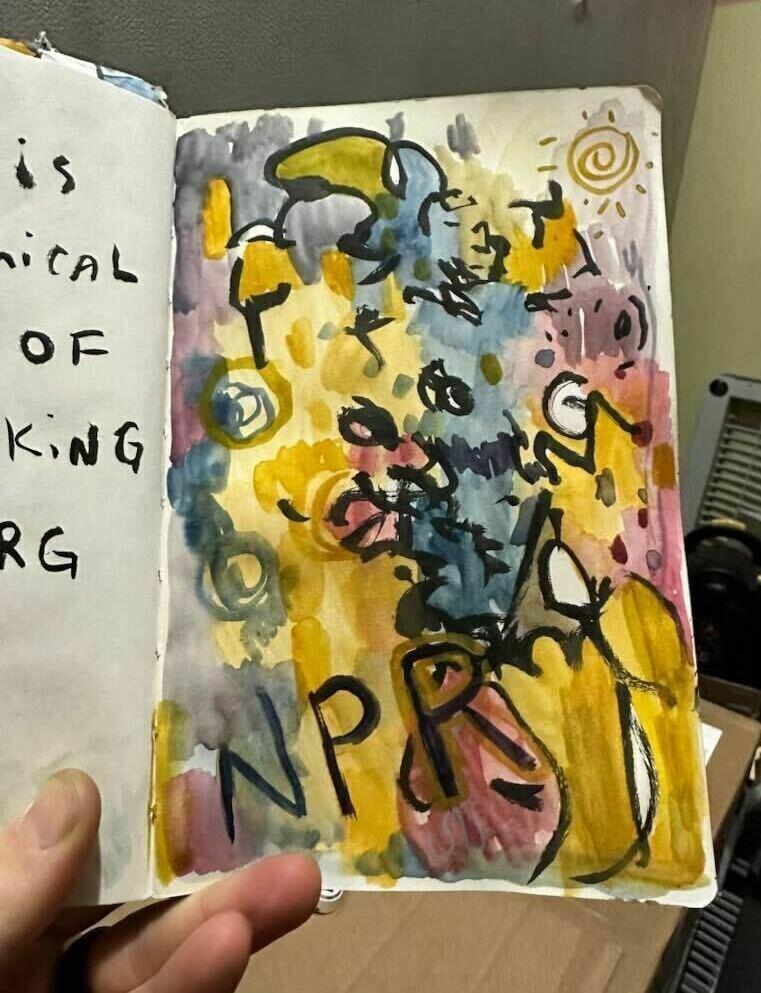

Roher, who has Attention Deficit Disorder, usually carries and paints out of a watercolor set because it helps him focus. He continued his brushstrokes and shared the latest news about Navalny during his conversation with Inskeep.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity. It includes some quotes from the interview with Roher that were not aired in the broadcast version.

Interview excerpts

What is it about Navalny that allows him to hold people's attention, whether he's on TikTok or in your documentary?

I think Navalny has a natural sort of God given charisma but more than that, he's just so funny. I think what's important and what scholars and academics will write about is how Navalny weaponizes humor to further his political ambitions. People love watching what should be dry investigative anti-corruption videos, and it's because he's so entertaining and so charismatic.

How does Navalny grow his base of support?

I know it seems impossible from the current landscape in the current history we're living through. But Navalny is the only politician in Russia other than the governing regime that has a national profile that every Russian knows. And it seems to be just a part of Russian history that if you want to make your mark, you have to do your time in the gulag. Well, Navalny is putting in his time, he's forced to. And although that's very challenging for all of us, he's a man who asks of his supporters optimism, whose worldview is geared and oriented towards optimism, who through two years of torture and prison, has not lost his singular sense of humor and his lightness and his spirit is unbroken. I think as long as his spirit is unbroken, hope for millions of Russians is also unbroken.

What do you think of Navalny's answer to your question about previously associating with far right nationalists?

His answer made me deeply uncomfortable. He essentially said, and people can watch the movie for themselves. But his essential answer was "the enemy of my enemy is my friend. How can I afford to alienate these crazy guys? Their goal is to get Putin out of power. And my goal is to get Putin out of power. Fine. We might as well join forces." Even though you know — this is me now, editorializing — their positions are deplorable.

What was your understanding of Navalny's thought process on returning to Russia?

Navalny went back with the expectation that he might have to sit in prison for ten years or five years. But he went back because he's a Russian politician and his people are the Russian people and he is deeply patriotic. And he saw it as his patriotic duty to go back and do whatever he could to get rid of this brutal, corrupt regime that is destroying his country. And whether you agree with his politics or not, everyone can agree that that courage in the face of unspeakable evil is righteous and it sort of has this quality, if not if not me. Who and if not now, when? Navalny was the man at the right time. And he was the last guy standing. He was the last meaningful oppositionist, the last meaningful opposition politician who went back to the country.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.