Section Branding

Header Content

A Camden grand juror speaks on the spaceport investigation

Primary Content

Mary Landers, The Current

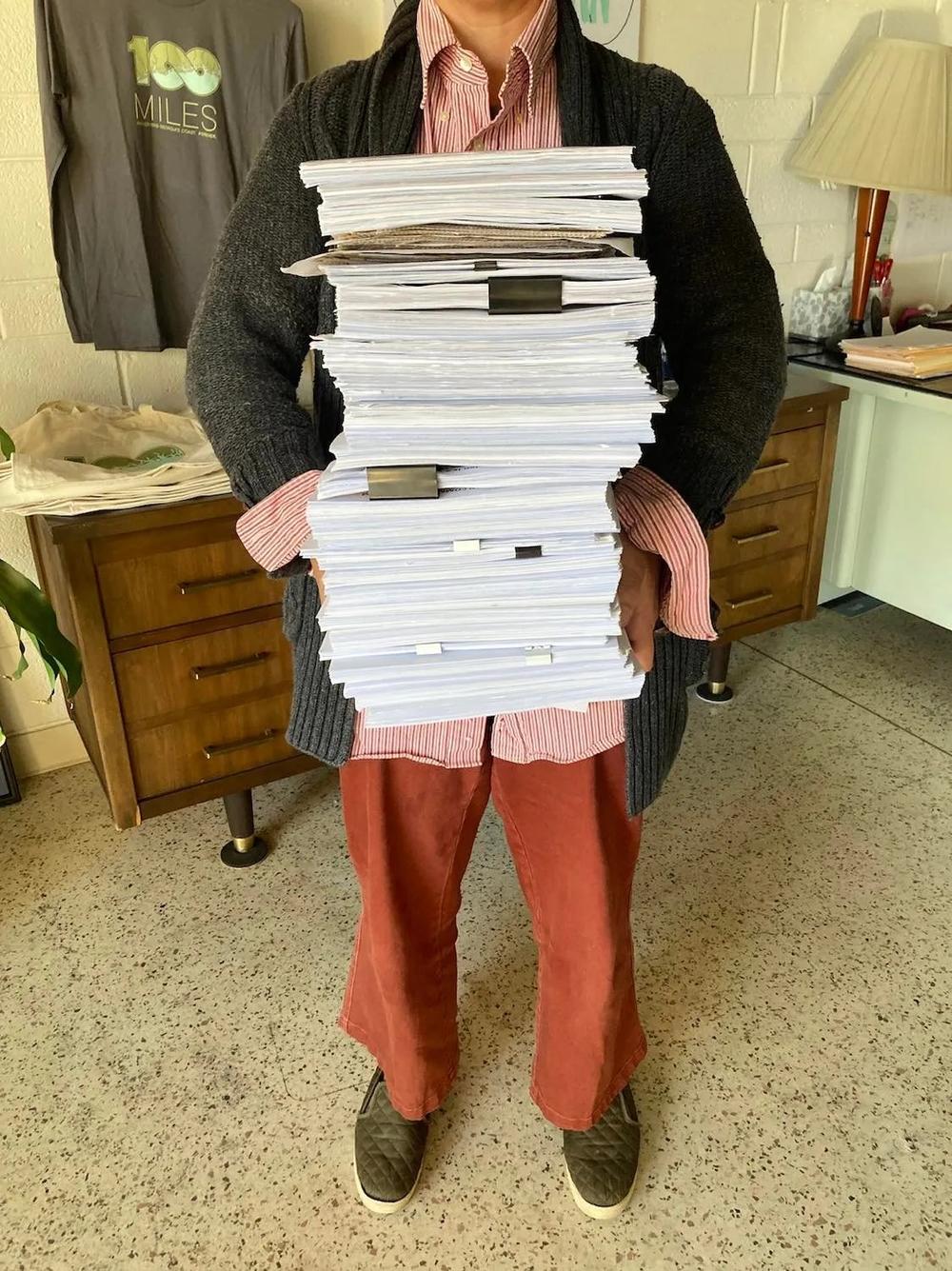

When a Camden County Grand Jury issued subpoenas in early March to county officials for information about Spaceport Camden, they received hundreds of thousands of documents in response. But the jurors had little time and even less guidance in analyzing them. The documents were disorganized and could only be viewed on a computer in the district attorney’s office under the supervision of a staffer. They weren’t even sure what they were looking for. And the clock was ticking on their term, which ended in early April.

The task was next to impossible.

“It was literally like having two giant haystacks and we didn’t even know if there were any needles in there,” said Christopher Walker, the juror who initiated the investigation. “But we were digging anyway.”

Initiating the investigation

Walker, who works in information technology, grew up outside of Atlanta and moved to Camden from Brunswick in 2007. He had always been civic minded, even considering a career as a lawyer, but he didn’t pay much attention to local politics.

He was familiar with Camden’s nearly decade-long, $12-million effort to establish a launch facility for commercial rockets on a former industrial site, but he hadn’t been active in either stopping or supporting the project.

“I mean, I knew about this case for a little bit, like I knew it had been this boondoggle,” Walker said in a telephone interview with The Current. “But it was not my fight. I wasn’t the type of citizen to get concerned or get involved.”

Spaceport Camden was controversial from the start, with proposed flight paths over private homes and tourists on nearby Cumberland and Little Cumberland islands. The Federal Aviation Administration granted Camden a launch site operator’s license in late 2021 contingent on the county gaining control of the proposed spaceport property, owned by Union Carbide Corporation. Citizens blocked the county’s purchase with a referendum in March 2022. Unwilling to give up, the county challenged the referendum in a case heard by the Georgia Supreme Court in October. The court’s decision was still pending when the grand jury convened in November.

Once Walker was called to serve on the grand jury he realized, “there’s really no oversight of county governments in the state of Georgia, other than the grand jury.” He learned this duty by reading the Grand Jury Handbook, a copy of which was given to each of the jurors. Under “Civil Functions & Duties” he saw how he and the other jurors could instigate an inquiry into spaceport. Optional investigations of county office required the support of only eight or more grand jurors, and a committee of the grand jury could inspect the county’s “records, accounts, property, or operations.”

I knew there were a lot of citizens out there that were requesting information that they should be able to have, because it’s public information. And it felt like that everybody was being sort of shut down by the county government. — Christopher Walker

“I thought, well, I’m in a unique position where maybe I can do some good,” he said. “I knew there were a lot of citizens out there that were requesting information that they should be able to have, because it’s public information. And it felt like that everybody was being sort of shut down by the county government.”

The county had frequently denied open records requests for spaceport records, citing mainly an exemption in state law for pending real estate deals. The nonprofit One Hundred Miles sued for the records in 2019 and earlier this month a judge created a timetable for the county to hand over documents.

The grand jury was convened in November, after the state Supreme Court heard oral arguments about the validity of the March 2022 Spaceport Camden referendum but before it issued its ruling. The 23 members and three alternates met once a month for about half a day each time. Walker bided his time in the first few meetings, thinking that a Supreme Court decision that upheld the results of the referendum would make an investigation moot.

“I really thought the county would be like, ‘Okay, we lost, that’s it, we’re gonna quit,’” Walker said. “But then when that Supreme Court ruling came out, the county’s response was to essentially double down on their position. Instead of saying, ‘the courts have spoken, that people have spoken,’ they basically said, 'ell, the law is wrong. We need to change the law.”

Walker was referring to a statement from the county that suggested Georgia lawmakers should change the law. It read in part, “Clearly, given the complexity of this decision on Home Rule and how it will impact local governments moving forward, this will be a matter that the General Assembly will need to address quickly to preserve the representative democracy we have in this great state. The future of Spaceport Camden remains a decision of the Camden County Board of Commissioners and as such will be discussed at a future meeting.”

The Supreme Court issued its ruling Feb. 7. At that point, the grand jury had only two months to go before its term expired. But the county’s response motivated Walker to take action anyway.

“I was like, y’all have missed the entire point of all of this,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Well, I’m gonna ask for an investigation,’ see if I can get the votes, and then I’ll just see what happens. And that’s how it all kind of started.”

Hurried work

At the grand jury’s next meeting in mid-February Walker asked for the investigation. He had the support of more than the required eight jurors. Two other jurors agreed to be on the committee with him, though only one other remained active. (That member declined to speak with The Current.)

“We knew we weren’t gonna have a lot of time, right? If I had known in November, what I know now I would have started the investigation our very first meeting,” Walker said.

They began by meeting with Spaceport Camden critics Steve Weinkle and Jim Goodman to get guidance on what to investigate.

Goodman was elected to the Camden County Commission in November after running on an anti-spaceport platform. He had been entangled in litigation surrounding spaceport, including being named as an interested party in the Supreme Court case. Weinkle ran for a commission seat, also with an anti-spaceport stance, but lost. A space enthusiast but fiscal conservative, Weinkle has long considered Camden’s space venture a waste of taxpayers’ money.

If I had known in November, what I know now I would have started the investigation our very first meeting. — Christopher Walker

Weinkle said he and Goodman guided the committee generally but couldn’t get too specific. In part his hesitancy stemmed from the fact that Weinkle’s long public criticism of the project made him something of a lightning rod; he didn’t want the grand jury’s work to be dismissed because of an association with him. “All I had to do was guide him in the right direction,” Weinkle said. “We didn’t breach any of the rules that would have caused the grand jury to get in trouble.”

Goodman confirmed that he met with Walker’s committee, but declined to share any details.

The committee gave Assistant District Attorney Robert German a list of items to subpoena. He issued subpoenas to the five county commissioners, County Attorney John Myers and County Administrator Shawn Boatright. They focused on financial issues, requesting invoices, bids, contracts and vendor reports along with associated communications.

Only Myers and Commissioner Goodman responded. Goodman, who was elected in November, 2022, indicated he had no documents to share. Myers responded on behalf of the Board of Commissioners, Chairman Ben Casey said in an email to The Current.

“The subpoena was for the production of evidence and as stated before, the county provided more information than was requested,” Casey wrote.

Walker also spoke with the forewoman of a 2019 grand jury that had also investigated spaceport, with a focus on the environmental impacts. That grand jury left a box of documents and instructions to continue its investigation, but they had had no luck in getting subpoenas, Walker said.

That’s because then-District Attorney Jackie Johnson, who is now charged with hindering the investigation of Ahmaud Arbery’s murder, declined to issue them.

“(Johnson) would say things like, oh, well, you catch more flies with honey, let’s just ask nicely,” Walker said the grand jury foreperson told him.

When the new materials were finally delivered they were digital records. The jurors were allowed to view them only inside the district attorney’s office with a staffer present, further limiting their investigation.

“There were a lots of times that we wanted to go up there for a few hours, and they were busy with court or whatever, and they didn’t allow us access,” Walker said.

Walker estimates he and the other active committee member each spent about six hours with the documents. Given that there were more than half a million emails alone, the time was too short.

And the information was in disarray. Walker works in IT, so he’s familiar with organizing information.

“There’s probably a dozen different ways to export email contents into a format that makes it easier for the person that is going to just search it and look for specific things and whatnot,” Walker said. “The county did not do that for us. “

Instead, they exported each email into an individual file, making them impossible to search efficiently. The zip files that held the emails weren’t named or dated. The emails weren’t all spaceport-related. Some were spam.

“There was no order whatsoever,” Walker said.

While Walker was pleased to get the subpoenas in the first place, some requested items were missing. For example, the subpoenas requested all communication but only emails were provided, not text messages.

The grand jury handbook indicated he could ask for technical assistance: “The Grand Jury is authorized to appoint one citizen of the county to provide technical expertise during the inspection or investigation. This technical expert receives the same compensation as Grand Jurors.”

With little time remaining the committee went to the GBI and asked for an accountant or a forensic investigator to help guide them. GBI declined, explaining what appeared to be a Catch 22: They’d have to have evidence of a crime before GBI could help them find evidence of a crime.

“They only get involved when invited by a district attorney or a law enforcement agency, and only if there’s criminal action suspected,” Walker said.

The best hope for the investigation was a handoff to the next grand jury. In its formal presentation to the court, called a presentment, the grand jury made four recommendations regarding Spaceport Camden:

- “We recommend that the District Attorney’s office make future Grand Jurys aware that there might be recommendations for them in the previous Grand Jury report

- “We recommend that future Grand Jurys take up this investigation into the Spaceport and push for answers for the public.

- “We recommend that the County Commission release all unredacted documents related to the spaceport that have been withheld or previously released redacted.

- “(W)e recommend that the District Attorneys office petition the Chief Judge of the Camden County Superior Court to request the empanelment of a special purpose grand jury to investigate the spaceport.

Work continues

That last request mirrors one made even before the Grand Jury wrapped up. Around the time he was subpoenaed, Commission Chairman Casey also requested a special grand jury to investigate the Spaceport Camden project. As with Walker’s request to GBI, however, it wasn’t possible without evidence of wrongdoing upfront.

“I asked for a ‘special grand jury’ to investigate all things spaceport,” Casey wrote in an email. “However, the chief judge informed me that a special grand jury would need a basis for their investigation as in a known criminal act or malfeasance.”

Casey said he turned to the new grand jury last week.

It might be that there are people out there in the community who know more than the experts, because they are the ones who’ve been right from the beginning. — Christopher Walker

“Absent of those, I also had the option of asking the recently impaneled grand jury to investigate the issue of the spaceport,” he wrote. “I did this on April 19th.”

The grand jury will need to follow the same procedure as did Walker’s group, getting at least eight of the grand jury members to vote to investigate.

“As the vote of the Grand Jury is secret, I don’t know how they voted, but they have access to more than just the records that the previous grand jury asked for,” Casey wrote.

Goodman said he is in the process of requesting a Special Grand Jury as well.

Weinkle would like to see the current grand jury ask for witness testimony rather than just sift through subpoenaed documents.

“What they really need to do is they need to take some testimony because when you’re doing testimony, you can lead them to the right question,” Weinkle said. “That’s one of the problems about subpoenas, they don’t have enough depth or experience to know what to ask for.”

He’d suggest witnesses like himself, who have studied spaceport from the beginning but have not been inside the effort.

“It might be that there are people out there in the community who know more than the experts, because they are the ones who’ve been right from the beginning,” he said.

Walker is hopeful that the new grand jury will continue the effort. They’ve received encouragement not only in the presentment but also from an in-person handover from the prior foreperson. The foreperson told Walker that Superior Court Judge Anthony Harrison also encouraged the new grand jury to continue the “big things” the previous grand jury had begun.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.