Section Branding

Header Content

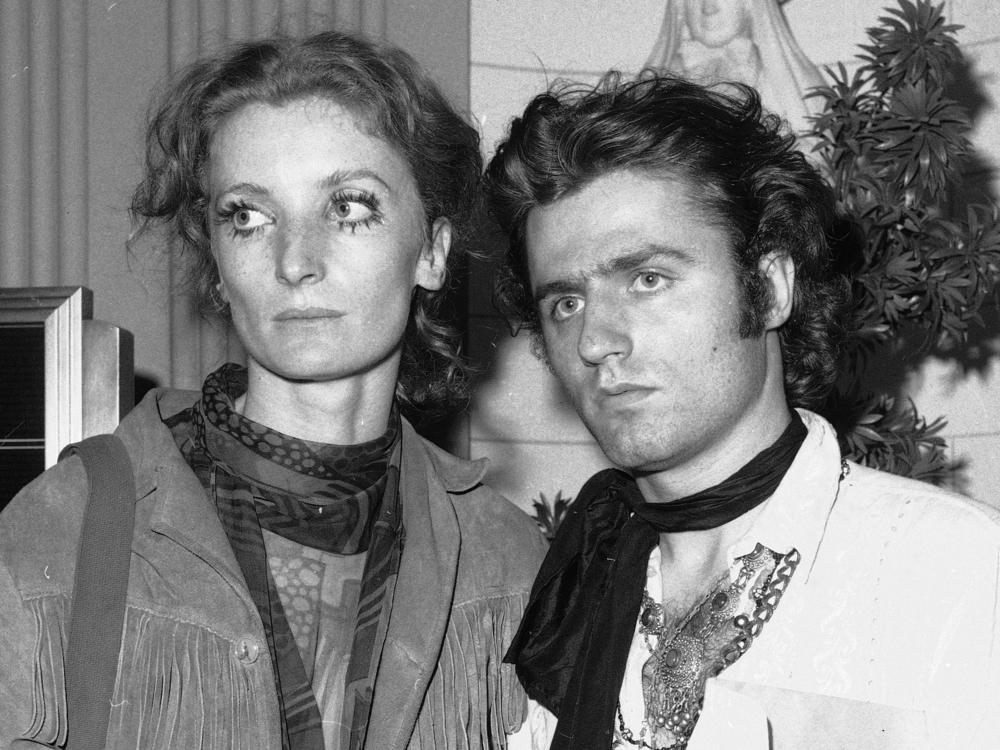

Daughter of Warhol star looks back on a bohemian childhood in the Chelsea Hotel

Primary Content

Alexandra Auder's mother, Viva, was one of Andy Warhol's muses. Viva appeared in the Warhol films Lonesome Cowboys and The Loves of Ondine, and she was on the phone with Warhol in 1968 when he was shot.

Growing up in Warhol's orbit meant Auder's childhood was an unusual one. As a kid, she played the daughter of a dominatrix in an underground film. After her parents split up when she was 5, Auder and Viva went on the road, traveling cross-country in a beat-up car with a cat they picked up along the way.

"It had no heat," Auder says of the car. "So at some point we were in the Rocky Mountains with no heat. And my mother would say, 'Oh God, my feet are just freezing to death,' and I would rub one of her feet while she was driving to keep them warm."

For several years, Viva, Auder and Auder's younger half-sister, Gaby Hoffmann, lived in the Chelsea Hotel in Manhattan, which was famous for having been home to Leonard Cohen, Dylan Thomas, Virgil Thomson, and Bob Dylan, among others.

"I absolutely loved living there," Auder says of the Chelsea. "Of course, there's transient people coming in and out. ... A 'normal' person might be horrified at the crowd — and there were often cops and some strange riffraff — but nobody was ever threatening to me at all. In fact, I loved the weirdos."

Auder is an actor whose credits include the HBO series High Maintenance. She's also a yoga teacher known for using Instagram to satirize the commercialization of yoga. She looks back on her unconventional upbringing in the new memoir, Don't Call Me Home.

Interview highlights

On her reaction to her mom's celebrity

When I was younger, I was very impressed with her and thought she was the most beautiful woman I'd ever seen. And I loved when people recognized her on the street, which would happen sometimes. I was very titillated by it. I thought she was the smartest, most wonderful woman in the world. And I think she just is who she is, so I don't think she thought about it like, "I want to be a celebrity" or "I'm a celebrity." She really was just living as she lived. And her convergence with Warhol was just one of those uncanny moments on the streets of New York at that time in the '60s that could happen, that could probably no longer ever happen again. ... I don't think it was an active thing on her part, but I think because she is a strong personality, I think she certainly enjoys attention.

On the deep bond she shared with her mother as a child

I think that a lot of single mothers have that relationship with their children, and especially if you're not wealthy and you have to work. My mother didn't have 9-to-5 jobs, but she wrote from home. I think space is a big issue. ... I think that sharing a bed for so long, it's almost the environment that creates that. But I do think that with Viva, with children, they are an extension of her. And that can be an amazing thing, up to a certain age. And she doesn't have a filter and she doesn't have boundaries. So in one sense, it creates this great like confidence, I think, in little kids, because you're treated almost as an adult in some way, and then certain aspects of that can go awry.

On Viva asking Auder if she should get an abortion when she got pregnant with Auder's half-sister, Gaby

Her saying, "Should I have an abortion?" ... didn't upset me at all in the sense that I wasn't shocked by the idea of abortion. I just knew, No, we're having this baby. And I would say "we" and I was absolutely certain I wanted a baby sister. It had to be a sister. And it was just outrageous to me, not because I thought abortion was bad or gross or anything, just outrageous to me that she wouldn't have this child that was meant to be that we had both prayed for. ... So I really thought that Gaby was a kind of destiny, our destiny. ...

Maybe I was a super weirdo at 11 years old, but I was so into the idea and I really felt this deep love for her and really wanted to be with her. As she became a toddler and I was then coming into my teen years, that felt different. I adored her, but I wanted some of my own time, so I felt more like a disgruntled mother by that point. But in those first couple of years, I was all in.

On her awareness of her father's heroin addiction

I didn't exactly know what heroin was, but my mother would always refer to him (French photographer Michel Auder) as a junkie. I knew there was something going on and that it was drugs, I suppose. And it made me very uncomfortable when I knew he was doing it. But I don't think I had an intellectual grasp of what it was. But I definitely felt very uncomfortable. It's hard to say which was more uncomfortable – my mother yelling about it a lot, and asking me to call him and tell him I know or talk to him or confront him and even calling him, or being in his loft in Tribeca, knowing he would sometimes do this thing, this mysterious thing. I almost preferred to just dissociate for a couple of minutes and wait till the process was over and then come out, because when we were together, he didn't seem high to me at all. I actually really enjoyed his company.

On writing about her occasional fantasies about wanting to smother her mother (in their adult relationship)

I think all women have that experience with their mother at times, and hopefully some less than others. But I think for whatever strange ... primordial, primitive animal [reason], we have that kind of repulsion to our mothers at times in our lives. So there's that. But then I think with ... Viva, who is difficult to contend with ... the constant monologue, the drama, the histrionic nature of her personality can be very overwhelming. It can also be hysterically funny and wonderful and a real joy ride, but in its darker moments can be very overwhelming. So, yes, I think from growing up in such a confined space and having had to deal with that from birth onward when she would come into our lives. ... I would feel that sense of claustrophobia. ... There is an internal violence and rage that simmers ... probably because I could never express any of that as a child. ... I wanted to be transparent and authentic when I wrote about that.

On feeling like Warhol discarded her mother

I really saw that there is a deep misogyny at that time. I think now things are very different, but I think I do see my mother as being discarded when she was no longer useful to Warhol, to certain directors, to the world. ... I do see that for women in that era, you had that moment. And then once you got to a certain age, it was over.

Thea Chaloner and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.