Section Branding

Header Content

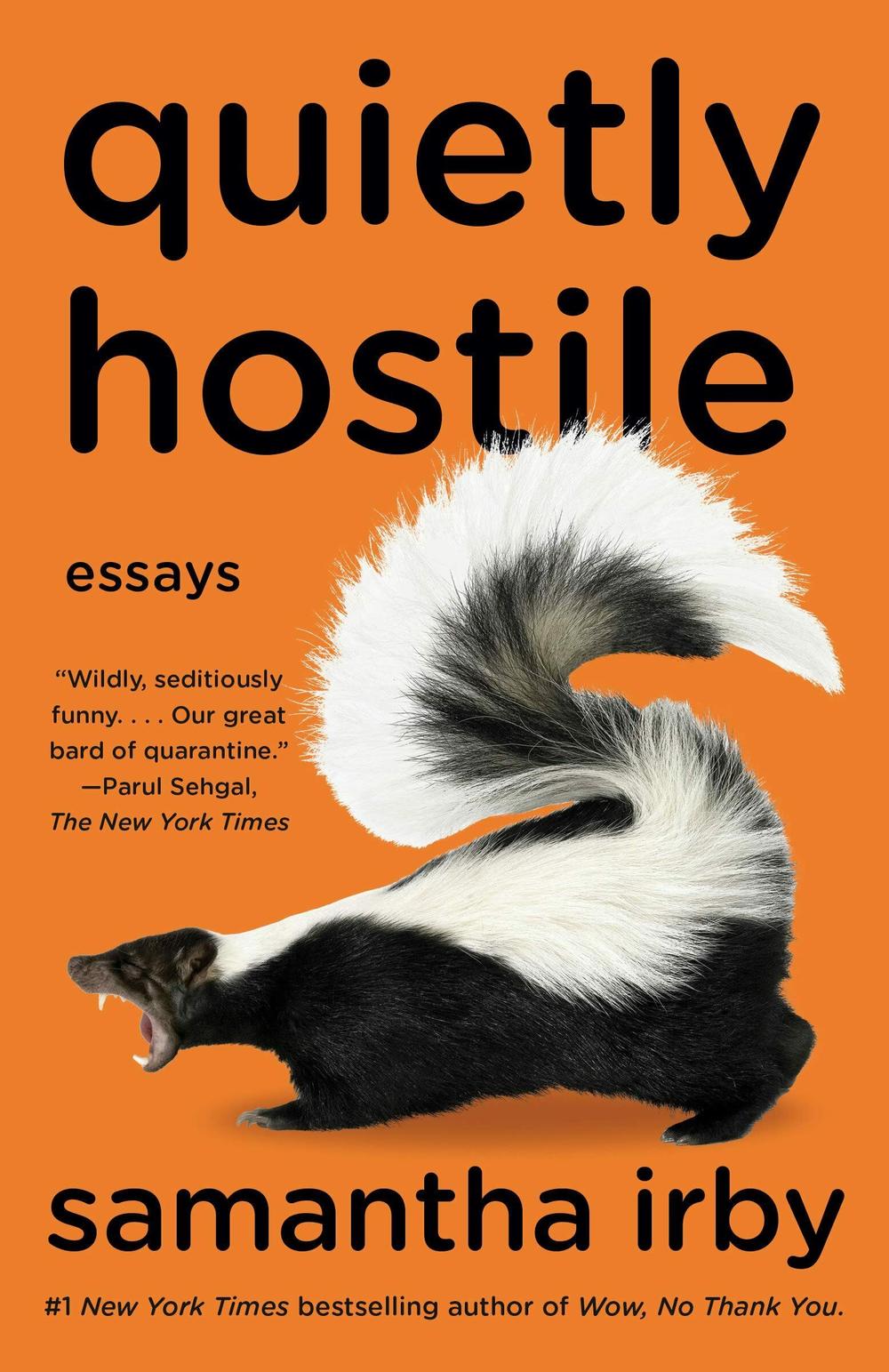

'Quietly Hostile' is Samantha Irby's survival guide (of sorts)

Primary Content

Humorist Samantha Irby is not afraid to tell you about her mental health struggles, the "glamorous hoarding" in her house or her bowel movements. She's made a career out of writing about these things, and spinning them into comedy.

So is there such a thing as oversharing? Irby says whatever she writes about, she has to be prepared for it to follow her for a long time.

"When you put a book out into the world, you have to be prepared for people to talk to you about it until you die," she says. "If I can't have a conversation with a stranger about the thing that I wrote, I won't put it in a book."

The title of Irby's new memoir in essays, Quietly Hostile, was inspired by her own public persona, which she describes as a "a constant low-grade frustration with everything" wrapped in "an outer shield of Midwestern politeness and charm."

She says the deaths of her own parents when she was 18 opened her up to living life on her own terms — and writing about it: "Excuse the callousness of this, but it's real: Dead parents, you can do whatever you want. Truly."

In the book, Irby chronicles a variety of funny situations, including her rise as a TV writer on the Hulu series Shrill and the trials of getting turned away at swanky LA restaurants for not dressing hip enough. She also writes about almost getting a popular cable network to adapt her first book into a TV show — the operative word being almost.

Irby refers to her memoir as a survival guide, of sorts: "I have some tools and tricks that if people want to adopt, it'll get them from point A to point B, because that's essentially what I'm doing," she says. "I don't have any long-term goals. I don't make any plans. I just am trying to find a way to get to whatever is happening after this."

Interview highlights

On why she has no interest in doing stand-up

I wouldn't consider it because ... it's the only medium where the audience is encouraged to be rude to the person on stage, and I can't get heckled. Like, I will pass away on stage if I get heckled. Oh, my God. Just thinking about it, I'm going to break out in a cold sweat.

On her recent OCD diagnosis

The pandemic really broke my brain. I didn't leave the house at all, like, for two years, and I sort of regressed into this feral creature who all of a sudden was terrified of everything outside. In the grocery store, I'd feel like people were chasing me, or in the car I always thought people are trying to run me off the road. ... So I found a psychiatrist who's really great. And we talked, and I described the way I think and ... some of my habits, and she was like, "Yeah, that's OCD." ... I thought it was just, like, hand-washing and checking the light switch a million times. But no, it's a lot of stuff that I do, like glamorous hoarding and ruminating on the same thought for two years.

On how the isolation of pandemic lockdown made her paranoid

It was so bad. As an inside person, I thought I was made for quarantine, right? Like, I hate going places. I had a book come out at the beginning of the pandemic, and I didn't have to go anywhere to sell it to anyone. I could just sit in my chair and do a virtual thing and talk to people on the computer and that felt really great. But, like, a year into that, I could feel myself kind of shriveling up.

Just not talking to people or seeing people or interacting with people made everyone seem like a danger to me. Once we were free, or once I freed myself — I think I stayed holed up a little longer than most people — then I just was like, Oh, everyone looks like they want to attack me. Meanwhile, no one cares about me ever. No one's watching me. No one's noticing what I'm doing. But it was like every person on the street posed a threat in my mind. It was scary enough for me to call a psychiatrist [that] I have to pay out of pocket, so, pretty terrifying!

On writing the "fat babe" pool party episode of Shrill

We had a 10-episode season and we knew that we wanted Annie to have kind of the same epiphany that [show creator] Lindy [West] had. ... We needed to come up with a vehicle that would be like something that would open her eyes. And Lindy and I both had been to separate fat babe pool parties. I went to the Chunky Dunk and there are some others, and we've been to fat girl exercise classes and fat girl clothing swaps, that kind of thing.

And we just wanted a catalyst through which Annie would emerge feeling better about being fat. And we thought a pool party would be great, because then we could do a thing that I don't know that has ever been done – nobody research and tell me – but like actual fat people in bathing suits on TV. I was like, if we get away with this, it's going to feel like a coup.

So I wrote the episode, I turned it in, and then I remember walking in and seeing the pool and being like, "Oh my God. This is perfect." What a vision. And then, because I'm always waiting for the other shoe to drop, I was like, "Oh, but is this room full of extras going to be like 'Hollywood fat?'" I was worried that I would go in to say hello, and — there's nothing wrong with a size six, but that is not a fat person or a size eight, even — and I was just holding my breath, like, Oh, please.

And then Lindy and I walked in to say hi to all the extras, and there were just all these big, glorious bodies being treated well. I don't want to divorce them from, like, being people, but it's the bodies you notice first. They were making custom swimsuits for people and hair and makeup was happening, and it was just like this beautiful dream. And I was like, I cannot believe that we get to do this. No one has let anyone do this since, so this might be our one unicorn fat naked people episode. But it was a dream. I still am in disbelief that we got to do it with no pushback.

On providing end-of-life care for her mother, who had multiple sclerosis

There was no like, help-mom-get-into-assisted-living-fund. It was just like, oh, we made all these decisions, then everything fell apart and now we're ill-equipped to deal with them. Good luck, Samantha! So that was hard. It's so hard to know in the moment what effect a thing is going to have on you. So now I can look back like, "Whoa, what a traumatic time!" But when it was happening, it was just like, "Well, this is my life. This is what I got to do."

On being bisexual and having a policy of not making fun of women

I have gotten some pushback from queers who are like, "You never write about the women you dated." I have a policy of not making fun of women, [only men] ... Not to turn this into Misandry Today, but come on! Of course they can take it. I also have never had a woman pull the kind of stuff men pull. I guess I could write about that lady I'd calmly watch TV with until it was like, "Man, this commute to your house takes too long. Let's stop seeing each other." ... Men are like bulls in China shops. At least the ones I have dated ... have given me fodder or hurt me in ways that I've spun into comedy.

On being open about Crohn's disease and bowel movements

The way we are about bathroom stuff as a society is bonkers, because it literally is a thing we all do. Why do we have to act like it's a shameful, secret thing that we're slipping off to do and lying and saying we've got to make a phone call? If I can free up even one person to just announce to a dinner party, "I will be gone. It will be longer than a minute. See you when I get back. Don't send out a search party," then my work on Earth is complete.

Sam Briger and Thea Chaloner produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.