Section Branding

Header Content

An exhibition of Keith Haring's art and activism makes clear: 'Art is for everybody'

Primary Content

In the 1980s, Keith Haring's cartoon-like images were everywhere — from t-shirts and New York City streets to art galleries around the world. His figures of dancers, hearts, babies and dogs remain pop culture motifs. Now, his art and his activism are featured in a major exhibition at the Broad Museum in Los Angeles.

The show Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody immediately transports visitors to New York City in the 1980s. The gallery spaces are even accompanied by music from his old mixtapes he and his DJ friends made.

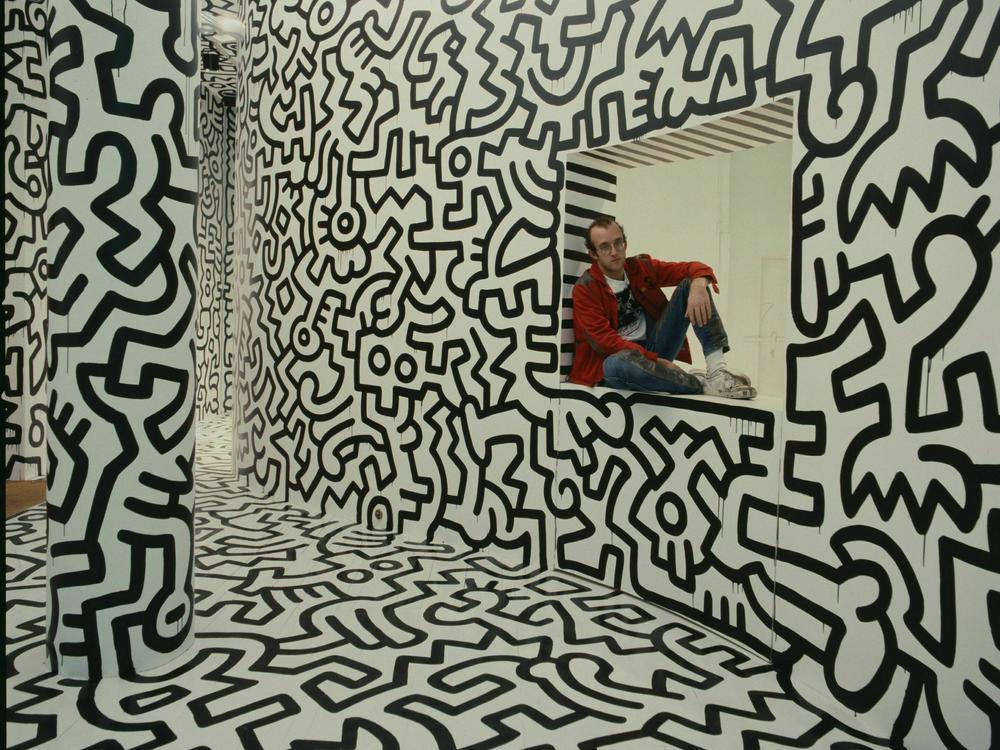

It opens with photos of the then-24-year-old artist working furtively underground. Inspired by hip-hop graffiti artists who spray painted subway cars, Haring used chalk on empty black advertising panels on the subway platforms. He drew simple outlined figures — most often, a crawling "radiant baby" and a barking dog.

"He stalks the New York City subways, waiting for his chance to strike," reporter Charles Osgood says in a video clip from CBS News in 1982. His report plays on a monitor at the beginning of the exhibition.

"You don't have to know anything about art to appreciate it," Haring explains in the clip. "There aren't any hidden secrets or things that you're supposed to understand."

Osgood continues: "He's got to be careful because technically what he's doing is illegal graffiti. Sometimes he is arrested. Haring doesn't think he is defacing anything. He believes it is art. And many subway riders seem to agree."

Haring's art was popular above ground, too, on street murals, on t-shirts, buttons and other merch sold at his famous Pop Shop in SoHo — and on big plastic tarps sold for millions. The Broad Museum has recreated his first major gallery show, painting stripes of day-glo pink and orange on the gallery walls, like Haring did.

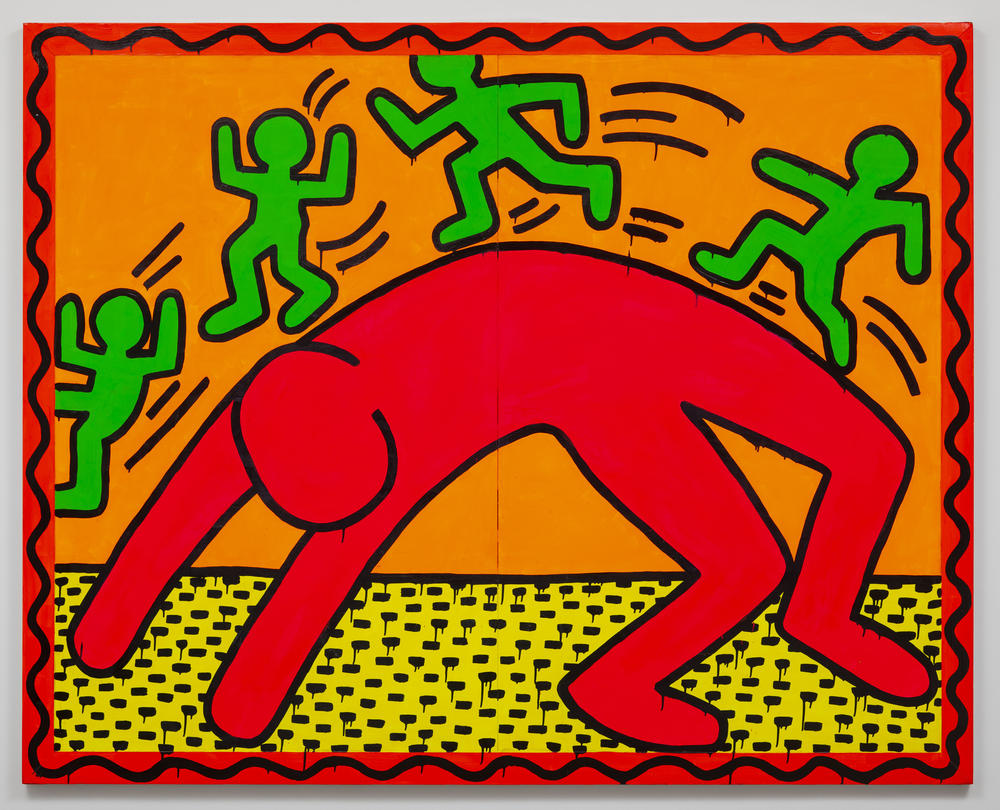

During a walk-through of the show before it opened, curator Sarah Loyer points out a painting of breakdancing figures. One figure is spinning on its head, with lines indicating motion — "they're really joyous imagery," she says.

Haring's work fills nine gallery rooms at the Broad, and includes a mini Statue of Liberty he decorated with graffiti artist Angel Ortiz, and pottery embellished with his own hieroglyphics.

"He created his own language with his own symbols, which is genius," says Kenny Scharf, another iconic artist of the 1980s. He says Haring left it to each viewer to decide what his art was all about.

"I would say The Radiant Baby would represent everything wonderful about being alive," Shcarf says, "And I would say the dog would represent nature"

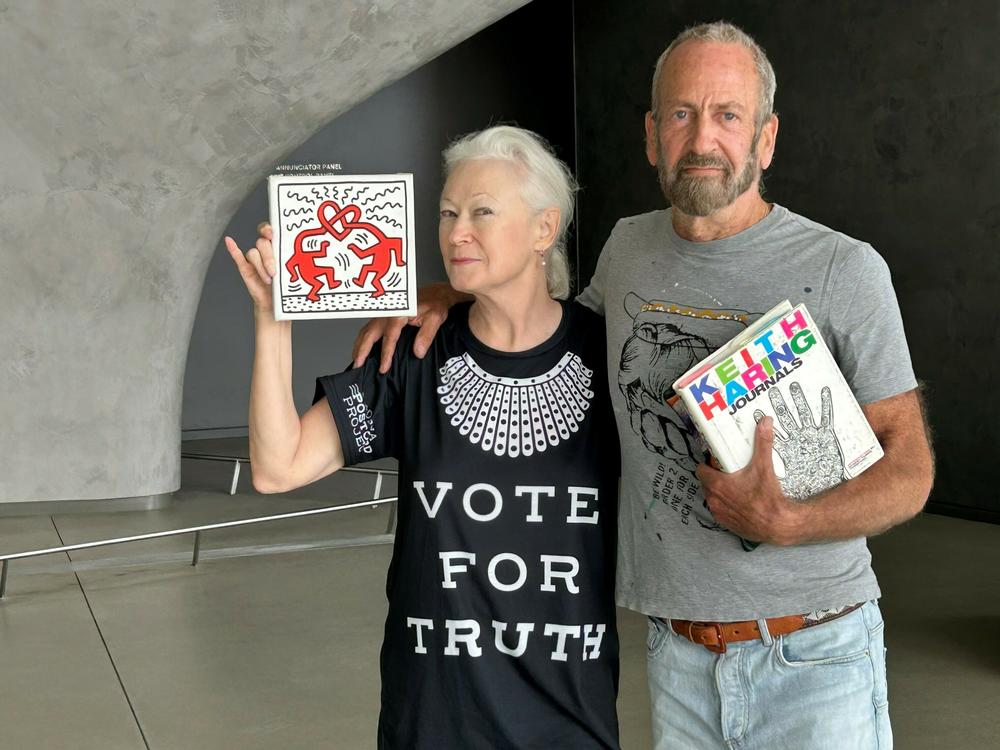

Scharf became close friends with Haring when they studied at the School of Visual Arts.

"Keith, was always ready to take over spaces that people were not using. And people really connected," Scharf says. "It was amazing to witness because I was his roommate at that time, and when he started doing those drawings, it was like he was everywhere."

Haring and Scharf were also fixtures in the downtown New York nightlife. He partied with people like Madonna, Andy Warhol and Fab 5 Freddy. They often danced at places like Club 57, which was run by performer Ann Magnuson.

"Keith was very Dada in a lot of ways," says Magnuson, who met Haring during a poetry reading at Club 57. "But he also balanced the silly fun part with very serious intellect and he loved to talk about art and the ramifications of it."

Scharf and Magnuson remember downtown New York in those years as a run-down dystopia and a creative, cutting-edge playhouse.

"It was a non-stop dance party. Daytime, nighttime, we were dancing, and Keith was very silly and fun," says Scharf.

"We chose to be down there in a very nasty part of town, but created a lot of fun and creativity, art, performance, poetry," says Magnuson, who remembers Haring carrying around a plastic white goose as a talisman. "We were in the Technicolor munchkinland world of our own making. And then the Black Death swept in."

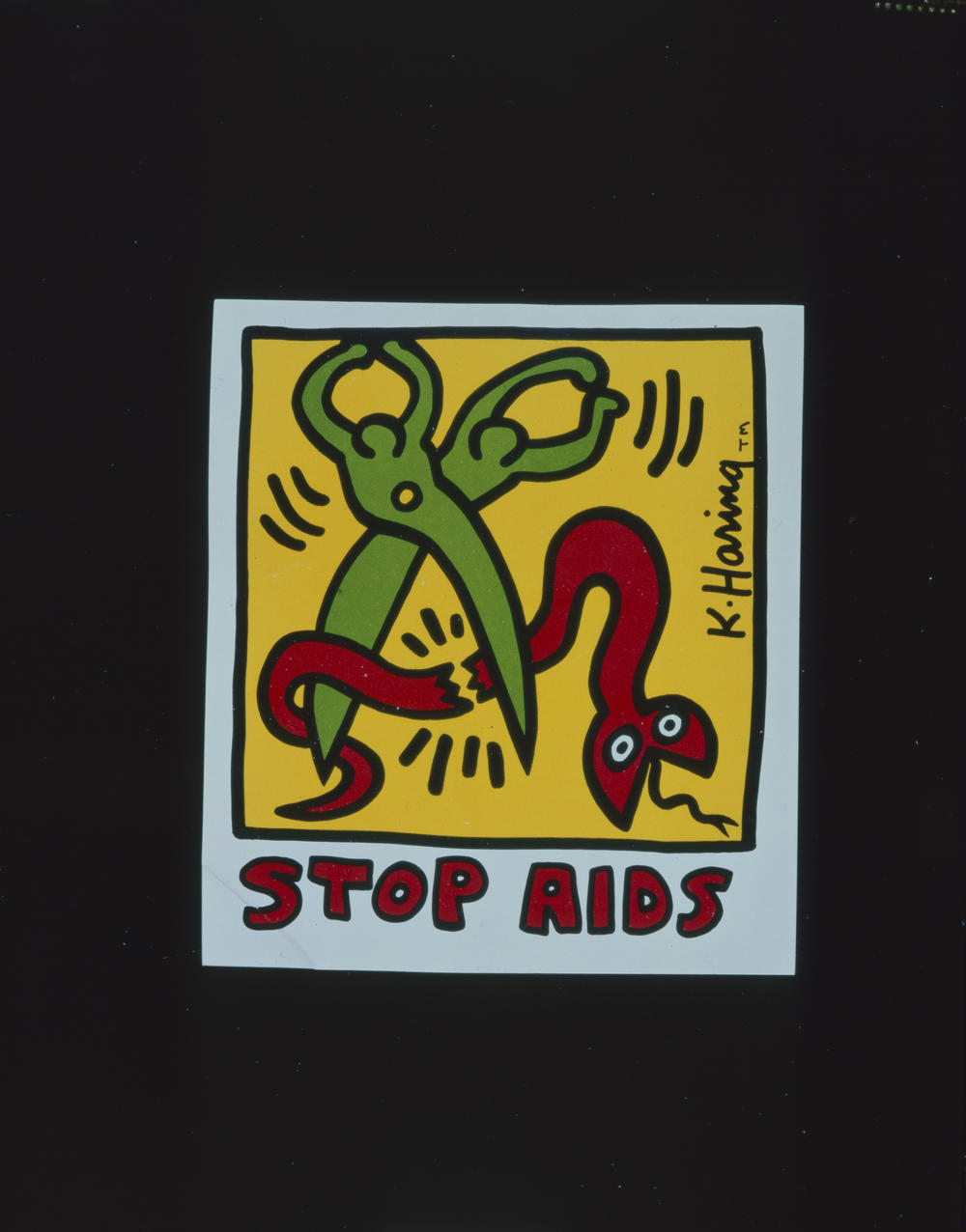

AIDS began taking the lives of so many friends, and Haring made it one focus of his work. He painted murals for gay men's health centers and created posters and art for the activist group ACT UP, which demanded government help for people with HIV and AIDS.

Scharf says Haring wasn't afraid to speak openly. "He came right out in Rolling Stone and said, 'Yeah, I have AIDS.' That was incredibly brave. Can you imagine opening yourself about being a gay person with AIDS back then? People were afraid even to be near someone with AIDS. Literally, he was shunned except by his closest friends."

Haring died of complications from AIDS in 1990, when he was just 31 years old.

His activist art, which went beyond AIDS, is a major focus of the new exhibition. Some of his work skewered President Ronald Reagan and capitalism; he warned about nuclear weapons and he protested apartheid in South Africa.

Gil Vazquez, who heads The Keith Haring Foundation, says his work remains relevant. "A lot of the things that Keith spoke up for — LGBT issues, or spoke up against — racial disparities, police brutality: These are things that persistent. You know, his art still really resonates."

The new Keith Haring show is just across the street from another exhibition of work by the late artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. Two groundbreaking, pop culture New York artists from the 80s. They both died young but are still creating a sensation.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.